By Mary Hotaling, Historic Saranac Lake and Rachel Bliven, New York State Historic Preservation Office

Introduction The dense urban streetscape of the village of Saranac Lake, New York, is a marked contrast to the vast stretches of unpopulated forest and tiny isolated hamlets that exist in the Adirondack region. The extraordinary building stock of Saranac Lake, with its multiple porches and walls of windows, its sophisticated commercial blocks and elegant residential districts, is the unique legacy of more than seventy years when this community was an international center for the the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Here doctors developed the first successful methods of treating — and even curing — a disease that had been the equivalent of a death sentence for almost all of recorded history. In so doing, they also developed a specific building type — the cure cottage — designed to facilitate the healing process for tubercular patients. Many of these cure cottages still stand in Saranac Lake, the most visible reminders of the village's days as America's "Pioneer Health Resort."

The incorporated Village of Saranac Lake is located in the Adirondacks, a jagged outcropping of mountainous peaks sliced by rapid-flowing streams and dotted with clear glacial lakes, which juts up out of the glacial plains of upstate New York. Six million acres of this rugged country and its isolated valley hamlets are part of the Adirondack Park, where 2.5 million acres of state-owned forest land have been protected as "forever wild" since as early as 1885. Deep in the heart of this wilderness, in a sheltered valley crossed by the winding Saranac River, lies "the little city of the Adirondacks."

The modern village of Saranac Lake is still the largest settlement within the Adirondacks. Its political boundaries cross both county and town borders: two-thirds of the village lies within the town of Harrietstown, in Franklin County; while the remaining third is split between the towns of North Elba and St. Armand in Essex County.

See also:

I. - Early Settlement (1819-1860)

During the Seventeenth and Eighteenth century, most residents of the Adirondack wilderness were native Americans. Camping sites on the shores of both Upper and Lower Saranac Lakes have yielded artifacts used by native peoples in hunting and fishing. Members of the Iroquois, Abenaki, and Huron nations used the uplands regularly as well as the lower elevations.

A small island in Lower Saranac Lake

A small island in Lower Saranac Lake

New York State first claimed the unappropriated lands of the Adirondacks in 1781 to serve as bounties for militiamen who served in the Revolutionary War. The 665,000 acres which are now Clinton County and parts of Franklin and Essex Counties were surveyed in 1786 and divided into ten-mile-square townships, but few soldiers were willing to take the rugged, interior lots. New York State later set aside additional lands in central New York to be used as military bounties, and these lots in the Adirondacks came to be known as the "Old Military Tract." The westernmost line of the Old Military Tract became the Franklin-Essex County line which still divides the village of Saranac Lake today.

New York State next offered the land within and to the west of the Old Military Tract for sale to investors and developers. On June 22, 1791, Alexander Macomb purchased 3,693,755 acres between Essex County and Lake Ontario, the largest grant of land ever made by the State of New York. His parcel included Franklin County and the western portion of what came to be the Village of Saranac Lake. Most of this tract was later sold to William Constable, who named the town of Harrietstown after his daughter.

Settlers were slow to move into the mountainous regions of the Adirondacks since better farmland was more easily reached elsewhere. The great flood of emigrants from New England bypassed the Adirondack wilderness because of its inaccessible terrain and difficult climate, moving further westward instead, through the St. Lawrence River Valley to the north or along the Mohawk River Valley to the south. Not until c.1800 did the inner valleys of the High Peaks region begin to have permanent settlers, when the Northwest Bay Road was cut through the wilderness from Westport on the shore of Lake Champlain northwest through Elizabethtown and Keene. Between 1810 and 1817 a series of Legislative appropriations were created to improve, upgrade and extended the Northwest Bay-Hopkinton Road northward to Hopkinton in St. Lawrence County, crossing the Saranac River where the Baker bridge stands today.

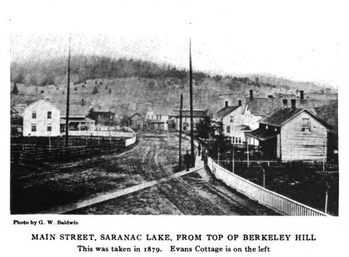

Earliest known photograph of Saranac Lake, 1877, by George W. Baldwin, looking up Berkeley hill from the Saranac River. Berkeley House, with the mansard roof is just left of center. The Old Academy is the white building left of the Berkeley.

Earliest known photograph of Saranac Lake, 1877, by George W. Baldwin, looking up Berkeley hill from the Saranac River. Berkeley House, with the mansard roof is just left of center. The Old Academy is the white building left of the Berkeley.

The Saranac Lake area was first settled by Jacob Smith Moody who built a cabin and cleared land in 1819 along the Northwest Bay Road. (The road still exists, now known as Pine Street within the village limits and Old Military Road in the Highland Park Historic District.) Moody owned sixteen acres of land which included the back of Helen Hill, Pine Ridge Cemetery (which contains his family graveyard), and Moody Pond.

In 1822, Captain Pliny Miller from West Sand Lake, Rensselaer County, the former commander of a militia company in the War of 1812, purchased 300 acres of land along the Saranac River in what is now Franklin County. His Wilmington, New York, lumbering business had been forced into bankruptcy by the failure of his primary Canadian customer, and he hoped to begin again in the Saranac Lake area. Much of the village of Saranac Lake stands on Miller's original purchase of land. In 1827 Miller built the first dam across the Saranac River to power his sawmill, creating a large mill pond where logs were gathered each spring for processing. This pond — large enough to be called a lake — was cleared of tree stumps in the 1890s and renamed Lake Flower, in honor of New York governor Roswell P. Flower.

Colonel Milote Baker, the last of the village's three pioneer families, did not arrive from Keeseville until 1852, when he settled on the land where the Northwest Bay Road crossed the Saranac River. Two of his daughters (first Narcissa, then Julia) married Ensine Miller, son of Pliny, who also farmed and owned two sawmills and a gristmill. By 1876, his son Andrew, a successful guide, built Baker Cottage by Moody Pond, on what is now known as Stevenson Lane.

The early village grew up along the triangle of roads (now River, Pine and Main Streets) which connected the farms of these three families and encircled Helen Hill. [Map #11] Farming, lumbering, trapping, fishing, and hunting, they made their living from the land and the wilderness around them. The area's remoteness from markets and lack of sufficient local demand prevented any greater use of the resources available. Log drives along the Upper Saranac River occurred as early as 1847, floating the logs down to Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain, but mills to produce finished wooden products locally were not to be built for many more years.

In 1849 Miller built the area's first hotel across the river from his sawmill, on the site of today's village water pumping station. Two years later the manager of Miller's hotel, William F. Martin, built his own hotel on Lower Saranac Lake about two miles west of the village, the first hotel in the Adirondacks to actually be located within the wilderness, rather than within village limits. Big enough to house eighty guests, the Saranac Lake House, more commonly known as Martin's, was considered an outrageous folly by local residents when it was first built.

In 1851, the same year as the opening of Martin's, regular stagecoach service was established between Saranac Lake and villages along Lake Champlain where connections could be made with lake boats traveling north and south. Standing at the northern end of the route, at the gateway into the wilderness, Saranac Lake was ideally located to serve travelers and sportsmen exploring the wild hinterlands.

By the late 1840s, upper class urban dwellers had begun to rediscover and idolize untouched wilderness. Wealthy sportsmen, called "sports," from cities downstate came to the Adirondacks on holidays, hiring local men to serve as guides to take them into the wilderness camping, hunting and fishing. Because of the primitive camping conditions and rugged traveling, few women ventured into the Adirondacks as tourists. This began to change with the opening of Martin's hotel and, in 1859, Paul Smith's family hotel on the shore of Lower St. Regis Lake, about fifteen miles northwest of Saranac Lake.

Mitchell Sabattis (standing between trees) with fellow guides Farrend Austin and Johnny Keller behind their "sports"

Mitchell Sabattis (standing between trees) with fellow guides Farrend Austin and Johnny Keller behind their "sports"

By 1854, Milote Baker had established a second hotel in the village, as well as a store and the first local post office, all at the present intersection of Main and Pine Streets. In 1856, Saranac Lake was a settlement of fifteen families scattered throughout the area and "a headquarters for lumbermen, guides and tourists."1 Local stores supplied campers, outdoorsmen, and villagers with fresh produce and staple goods in exchange for furs, hides, venison, farm products, or cash. By 1868, Milote Baker employed thirty men as hunters and shipped as many as 500 deer each winter to markets.2

In I860, on the eve of the Civil War, Orlando Blood opened a third hotel in the Village of Saranac Lake on the shore of the millpond. The Adirondack resorts prospered throughout the war as men escaping the draft and those who had paid others to take their places on the battlefield retreated to the mountains. 3

After the war, a prospering middle class, increased leisure time, and improved access by railroad to Lake Champlain made this area even more accessible for tourists. A major impetus was the 1869 publication of the Reverend William H. H. Murray’s guidebook called Adventures in the Wilderness: or Camp-life in the Adirondacks. His fanciful descriptions of the pleasures of the Adirondacks, coupled with specific information about travel and lodging precipitated "Murray's Rush," also known as "the greatest invasion of the north woods ever witnessed by the resort hotels."4 Summer hotels like Martin's and Paul Smith's were enlarged and new ones were built throughout the region. Paul Smith's Hotel grew as the center and impetus for a wealthy and cultured seasonal community whose financial resources would greatly enrich the area. Later in the century, wealthy families would buy land and build their own elaborate summer "camps," like Knollwood Club, and others.

The summer visitors brought no permanent population increase to the area, but they created seasonal employment for local residents, and their presence stimulated improvements in transportation and modern conveniences.

Local residents earned extra money by working as wilderness guides and taxidermists. Near Martin's Hotel, a small colony of buildings was established at the end of Lake Street and on Algonquin Avenue to house the homes and shops of these men. Their work was by nature seasonal, and the earlier pattern of multiple sources of employment continued (as it does to the present time) with local farmers and other villagers finding a number of ways in which to earn cash income.

A guideboat at the Adirondack Museum Many used the long winter months to build guideboats, the indispensable vehicle for traversing the waterways of the wilderness. First developed between 1825-1835 in the Saranac/Raquette/Long Lakes area and evolving over the years by modifications to traditional craft, these lightweight rowboats held from two to four persons yet were light enough to be carried by one man from one lake to another over distances of up to four miles. Guideboat manufacture was a significant industry in the town of Harrietstown which included the village of Saranac Lake. In 1875 twenty-two of them were made of light pine at an expense of fifty to seventy-five dollars each. 5

A guideboat at the Adirondack Museum Many used the long winter months to build guideboats, the indispensable vehicle for traversing the waterways of the wilderness. First developed between 1825-1835 in the Saranac/Raquette/Long Lakes area and evolving over the years by modifications to traditional craft, these lightweight rowboats held from two to four persons yet were light enough to be carried by one man from one lake to another over distances of up to four miles. Guideboat manufacture was a significant industry in the town of Harrietstown which included the village of Saranac Lake. In 1875 twenty-two of them were made of light pine at an expense of fifty to seventy-five dollars each. 5

Footnotes

1. Alfred Lee Donaldson, A History of the Adirondacks (New York: Century Co., 1921), p, 227.

2. Frederick J. Seaver, Historical Sketches of Franklin and its Several Towns (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Co., 1918), p.374.

3. John J. Duquette,'"The Saranac Lake House," Adirondack Daily Enterprise, August 13, 1986.

4. Alfred Lee Donaldson. A history of the Adirondacks. Vols. I & II. (New York: Century Co., 1921). p. 196.

5. Town of Harrietstown, Census of 1875.

Most patients saw their stay in Saranac as temporary, hoping to get well and return to their lives as they were before being interrupted by tuberculosis. For those who brought their families and could afford homes of their own, house rentals were quite common. Rentals were also an easy way for local investors to quickly pay for the cost of construction. As one visitor noted, "The rent for two years' occupancy of a cottage pays for building it." 1 Throughout the village, developers and contractors worked quickly to build new houses, not only because of the short Adirondack building season, but also because of the potentially short life span of their tuberculosis tenants.

Other contractors known to have worked in the area were J.J. O'Connell and George L. Starks, who also ran the Adirondack Hardware Company. William Edgar Trombley and John (Jack) Carrier" were both architects as well as manufacturers of building parts. Around 1898, Trombley & Carrier's "sash, door & trim establishment" was recorded in local papers as being badly damaged by fire.Branch & Callanan was a major local contracting firm, active in Saranac Lake's first building boom. Originally from the Keeseville area, they had a mill in Saranac Lake by 1896 which manufactured doors, sash, and blinds used locally and shipped elsewhere. By 1902, they had two mills as well as contracting services, and were advertising:

We can build your house from the ground and furnish everything. We have the facilities for building a cottage in two weeks as we have more than five hundred men in our employ. Don't wait to see us. Write, wire or telephone. 2

As contractors, Branch and Callanan built sixty buildings in 1908 alone, mostly in Saranac Lake and the vicinity. Many of the finest buildings in Saranac Lake were their work, as well as elegant Adirondack camps and homes elsewhere in the region. William Callanan, cofounder of the company, lived with his family at 19 Academy Street (nominated to the National Register).

The Village of Saranac Lake became incorporated in 1892, the first community in the Adirondacks to do so. Dr. E. L. Trudeau was named president and Milo Miller, trustee. The village was extremely conscious of the health of its citizens and was quick to provide funding for an unusually advanced infrastructure. A gravity system of waterworks was installed in 1893, soon followed by the construction of a full sewer system (1893-1912). In subsequent years they installed a fire alarm system and fire station, an incinerator for burning "garbage, swill, and refuse," and paved streets. Orlando Blood and others established Saranac Lake's first electric company in 1894, later selling it to the Saranac Lake Electric Company. Coal gas, produced at a plant on Payeville Road, was available for those who preferred it for light or heat.

In addition to paying for all sorts of projects which provided better health conditions, the Village Board of Health and local health code were among the best in the state. Ordinances against spitting, a major source of tuberculosis infection, were instituted. In fact, by 1920 village publicists were still able to claim "No known case of tuberculosis infection has ever occurred in the village." 3

The spiritual needs of local residents and visiting patients were served by four denominations. The Episcopal Church of St. Luke the Beloved Physician was one of the earliest examples of the impact of the new visitors in the village. The Reverend John P. Lundy, D.D., an Episcopal priest from Philadelphia, conducted services at the Berkeley Hotel in the winter of 1877 for fellow patients and others. He and the guests began a subscription for the construction of a church building on the comer of Church Street and Main Street, and local residents joined in. Dr. Trudeau completed fundraising for the project in 1879, and the nationally known New York church architect, Richard M. Upjohn, donated the plans for a simple wooden church in his well-known Gothic Revival style.

The First Methodist Episcopal Church of Saranac Lake, incorporated in 1878, held services in the schoolhouse and private homes before completing their sanctuary on Main Street in 1886. Their current building on Church Street was completed in 1927. Roman Catholics, incorporated in 1888, built the first St. Bernard's Church just off Church Street in 1892; the building on that site today is their third sanctuary. The First Presbyterian Church began as a mission church in 1890, but the congregation was able to dedicate its own building by 1891; it still stands in somewhat altered form at 23 Church Street. Three of these denominations are represented in the Church Street Historic District nomination.

Late in 1893, Dr. Trudeau’s house on Main Street with its small laboratory addition burned to the ground while the family was in New York City. The house was rebuilt and Trudeau’s friend and patient George Cooper paid for the construction of a new "fireproof" stone laboratory in a separate building behind the house, the first facility in the United States designed for and devoted to tuberculosis research. Both Trudeau's new Colonial Revival house and the Saranac Laboratory were designed by his cousin, J. Lawrence Aspinwall, a partner of the architect James Renwick. The Saranac Laboratory for the Study of Tuberculosis became nationally noted for its bacteriological work with tuberculosis. Using chemical tests as well as animal experimentation, researchers here made significant advances in the study of tuberculosis as well as other lung diseases such as silicosis.

As the curing industry continued to grow, it stimulated the entire economy of Saranac Lake. Soon it supplanted the guide and tourist business as a major source of income for local residents. In the ten years between 1892-1902, ten blocks of commercial structures were built in the downtown business district, in an urban scale and sophisticated styles for what was still a remote area. Many of the commercial structures are included in the Berkeley Square Historic District.

Main Street, looking North, 1908

Main Street, looking North, 1908

Nine of these commercial blocks are modest examples of popular nineteenth century commercial vernacular architectural styles. The early buildings reflect their remote location through their builders' use of local materials and modest detailing. They also reflect the conservative approach of their builders to the onset of an unprecedented prosperity; three of them were built in two parts, expanding onto an adjacent site as business warranted or funds allowed. The cautiousness of this approach reflected the unanticipated and incremental growth of the village as a health resort.

From 1902-1920 existing buildings in the commercial district were expanded and new ones added to the streetscape. Often the upper floors were used for rental apartments, with large cure porches incorporated into the architecture to the front and rear. The Leis Block and other such structures throughout the Berkeley Square Historic District are fine examples of this.

By 1903 Saranac Lake was "a town of four thousand inhabitants... known both here and abroad as a health resort." 4 It continued to grow as tuberculosis patients flocked to the area to regain their health. Local stores catered to all the needs of their customers, including some peculiar to this community. Many were groceries and pharmacies, providing imported delicacies, painkillers, and other nostrums. Others advertised sputum cups, chair robes and fur coat rentals for patients curing outdoors.

A Cure Chair Beginning at the turn of the century, five local firms manufactured another essential piece of equipment: the cure chair. This customized chaise lounge made the patient's long hours outdoors more comfortable. George L. Starks and Company at 29-33 Broadway was the most successful manufacturer, selling the Mission-style "Rondack Combination Couch and Chair" throughout the United States and Europe. 5

A Cure Chair Beginning at the turn of the century, five local firms manufactured another essential piece of equipment: the cure chair. This customized chaise lounge made the patient's long hours outdoors more comfortable. George L. Starks and Company at 29-33 Broadway was the most successful manufacturer, selling the Mission-style "Rondack Combination Couch and Chair" throughout the United States and Europe. 5

Two national banks served local financial needs. The first of them, the Adirondack National Bank, was founded in 1897 by three recovering tuberculosis patients, William Minshull, John F. Neilson, and Alfred L. Donaldson (who later would write the first comprehensive history of the Adirondacks). Its 1906 headquarters at 70 Main Street still stands within the Berkeley Square Historic District, its facade obliterated by 1962 alterations.

A Winter Carnival was first sponsored by the Pontiac Club in 1898 and attracted thousands of onlookers for four or five days of parades and public events, including fireworks over a spectacular ice palace on the shore of Lake Flower. The tradition has continued almost without interruption to the present day. A free public library, founded in 1880, was established in its own permanent building by 1918, built largely with private donations.

A Village Board of Trade, precursor to the Chamber of Commerce, was established in 1905. Under its auspices, the landscape design firm of Olmsted Brothers was retained to prepare a master plan for improving the village. Their recommendations included the creation of a village park system encompassing the shores of Lake Flower and the Saranac River. In response, the Village Improvement Society was founded in 1910. They cleaned and beautified the lake and have continued to this day to work on the full implementation of the Olmsted Brothers plan.

The village's first train station burned in the 1890s and was replaced in 1904 by the Union Depot, uniting the New York Central and the Delaware & Hudson Railroads after the D&H was converted to standard gauge railroad tracks. The large size of the station and its six-hundred-foot platform reflected the volume of business at that time. New tuberculosis patients and supplies arrived daily, and every night the coffins of the dead departed on their final journey home.

Just outside the village, large new sanatoria were built by private foundations or government entities to be close to the medical resources and other facilities of Saranac Lake. In December 1894, only ten years after Trudeau established his sanatorium, the Sisters of Mercy established Sanatorium Gabriels for patients with incipient tuberculosis, about eight miles north of Saranac Lake in the Town of Brighton. Stony Wold Sanatorium, devoted particularly to the care of working women suffering from tuberculosis, opened in 1902 in the Town of Franklin, Franklin County, with the support of the Newcomb, Gould, Potter and Morgan families, the New York Telephone Company, and the E.I. DuPont de Nemours Company. About four miles southeast of Saranac Lake, in Ray Brook, N.Y., the "State Sanitarium" began in 1900 as a summer tent sanatorium. In 1904, the Ray Brook State Hospital opened a beautiful year-round facility. It is one of the few that still stand, now a medium security state prison. Because a patient's care at Ray Brook was totally subsidized by the state, it was often the last stop for those who could no longer afford private quarters or the semi-charitable institutions.

State Sanatorium at Ray Brook, under constructionBy 1907, four hundred Americans were dying of tuberculosis every day and hundreds of infected patients flocked to Saranac Lake in hopes of getting into the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium. Many had made no advance arrangements for housing, and as their numbers multiplied, the Saranac Lake Society for the Control of Tuberculosis (the TB Society) was founded to help control the chaos. Acting as a central clearinghouse for information, the TB Society maintained a registry of local cure cottages and regularly inspected them to assure certain basic standards of quality and care. Unregistered cure cottages provided additional beds for the overflow of patients. Almost every local family took in a boarder at least once, providing rooms when personal finances or interests and the market required them.

State Sanatorium at Ray Brook, under constructionBy 1907, four hundred Americans were dying of tuberculosis every day and hundreds of infected patients flocked to Saranac Lake in hopes of getting into the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium. Many had made no advance arrangements for housing, and as their numbers multiplied, the Saranac Lake Society for the Control of Tuberculosis (the TB Society) was founded to help control the chaos. Acting as a central clearinghouse for information, the TB Society maintained a registry of local cure cottages and regularly inspected them to assure certain basic standards of quality and care. Unregistered cure cottages provided additional beds for the overflow of patients. Almost every local family took in a boarder at least once, providing rooms when personal finances or interests and the market required them.

In addition to the cure cottages on Helen Hill and French Hill, patients were soon able to find lodging in a new neighborhood almost exclusively dedicated to commercial private sanatoria. Developed by Julia Miller on a narrow plateau of Mount Baker overlooking her lots on Margaret and Catherine Streets, the new lots averaged about 1/3 acre in size. The section numbered 28-96 Park Avenue, where almost every building was a commercial private sanatorium, came to be called Cottage Row. It became one of the most densely built-up and best known concentrations of cure cottages in the village. Twenty structures designed and originally built as cure cottages are included in the Cottage Row Historic District.

The influx of tuberculosis patients included many wealthy individuals who came to Saranac Lake in search of the most advanced methods of treating tuberculosis. The real estate agency of Duryee & Co., founded in 1909 by George V.W. Duryee, Walter Cluett, and Eddy Whitby, specialized in renting properties to prominent or prosperous health seekers and summer vacationers. Many houses in Highland Park were thus leased out over the next few decades.

The Clark-Peyton Cottage in Rockledge

The Clark-Peyton Cottage in Rockledge

Also in 1909, the same three men organized the Rockledge Company to build Saranac Lake's second exclusive subdivision. Walter Cluett had been instrumental in hiring the Olmsted Brothers firm to prepare the village improvement plan, and the same firm was retained the following year to lay out a subdivision plan. Located on 73 acres of Col. Milote Baker's farm, Rockledge included almost all the land between East Pine Street and the Saranac River, in addition to a quarter of Moody Pond. It was laid out in fifty lots ranging from 1/3 acre to three acres in size. Physically separated from the village center by Helen Hill — although no farther than Highland Park — the area seemed remote and was slow to develop. Only six houses had been built on Rockledge Road by World War II.

The last of Saranac Lake's three upper class neighborhoods, the Glenwood Estates Colony, was quicker to develop. It was established just one year later than Rockledge, in 1911, by a local partnership of Dr. Lawrason Brown, banker William Minshull, and merchant William C. Leonard on 120 acres of Dewey Mountain's lower slopes above Riverside Drive. Like Highland Park, the lots in Glenwood had explicit deed restrictions to protect property values and attract the most discriminating buyers, the regulations were the most restrictive in the village and included regulations that the dwelling house must cost at least $5,000 and could stand no closer than 25 feet from the property lines. Of the twenty-six building within the area, about eighteen were built in the curing era, most by 1930. Residents and tenants included members of the Wrigley and Edison families, Dr. Francis B. Trudeau, architect William G. Distin, Sr., and a vacationing Albert Einstein.

Footnotes

1. Thomas Bailey Aldrich, 1903, in Robert Taylor, America's Magic Mountain (New York: Paragon House Publishers, 1986), p. 107.

2. Adirondack Daily Enterprise July 3, 1902.

3. Donaldson, p. 242.

4. Gallos, p. 16

5. Gallos, p.14

II. - In Pursuit of Health — The Rise of the Curing Industry (1860-1881)

Among those who came to the Adirondacks in the mid-nineteenth century were people who came to the mountains in search of relief from illness. Reverend Murray wrote in 1869 about the dramatic recovery of a tubercular patient who entered the mountains an invalid and returned a healthy outdoorsman. Other books about the region mention the health-giving qualities of the climate, as much as fifteen years before Murray's book. As early as 1860 guests could be found at Martin's hotel who had come for the summer to recover from tuberculosis. In fact, a later guidebook was to call Martin's "a most desirable tarrying place for all in quest of health or sporting recreation."

The quest for health in the nineteenth century was more than the narcissistic self-improvement fads of modern times. For many, the search was a matter of life or death. The "White Plague" ran rampant for much of the century. The number of Americans infected with tuberculosis in the nineteenth century was as great as the combined number of cancer and heart disease patients today. By 1873 Tuberculosis, also called consumption, killed one out of every seven Americans in a slow but unalterable physical decline. 1 It was primarily a lung disease, but the tubercle bacillus could attack any part of the body. Once lodged, the infection spread unchecked, steadily wearing down the body's defense system, and eventually creating cavities in the lungs. At its more advanced stages the best-known symptoms were coughing, night sweats, paleness, weight loss, virulent sputum, and spitting up blood. There was no known cure.

Transferred by airborne bacilli, the disease spread rapidly in enclosed or crowded environments, threatening immediate family members as well as neighbors. Slum dwellers and struggling factory workers were especially vulnerable, as were the very rich, paradoxically, who employed servants from poor living conditions who unknowingly harbored the disease. The disease did not confine itself to the very old and the very young, but instead most frequently struck people in the prime of their life. 2

In its sheltered position in a deep basin of hills, the village of Saranac Lake had begun to attract invalids as early as 1860 with the opening of Martin's Hotel. Until the 1870s, however, none of these patients seemed to have braved the frigid winters of the Adirondacks. The first tubercular patient credited with staying year-round in Saranac Lake was Mr. Edward C. Edgar who spent the winter of 1874 at the boarding house run by the wife of Lucius Evans, a well-known local guide. At this time, the village of Saranac Lake was little more than a saw mill, a small hotel for guides and lumbermen, a schoolhouse and perhaps a dozen guides' houses scattered over an area of an eighth of a mile. 3

Another contemporary description mentions 50-60 log houses in town. The population numbered about four hundred, and there were no newspapers, no lawyers and no churches. The nearest train station was in AuSable Forks, 42 miles away, but the stagecoaches ran regularly and a telegraph connected the village with the rest of the world. [Map #2]

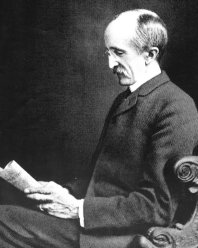

Up to this time, Saranac Lake was similar to many other hamlets within the Adirondacks. The person who almost single-handedly altered this pattern of development was Dr. Edward L. Trudeau, who arrived in the village in 1876.

Edward Livingston Trudeau was born in New York City in 1848. His father was a doctor from New Orleans and his mother was French. Men in his mother's family had been physicians in France almost as far back as the family lines could be traced. His parents divorced when Edward was young, and he spent much of his childhood in France, returning to New York with his grandparents at the end of the Civil War.

Trudeau was friendly with and related to some of America ' s wealthiest and most prominent families, including the Aspinwalls and the Livingstons, and he led the carefree life of a dilettante on his return to the States, finally enrolling in the Naval Academy in 1865. A major turning point came that fall when Edward's older brother Francis contracted a very virulent and rapidly progressing form of tuberculosis. Edward, seventeen years old, left school to nurse his brother full-time for three months. Francis died two days before Christmas, 1865. Edward later wrote in his autobiography:

"This was my introduction to tuberculosis and to death. It was my first great sorrow — and I have never ceased to feel its influence. In after years it developed in me an unquenchable sympathy for all tuberculosis patients.4

For the next three years, Trudeau continued his rounds as one of the "smart social set" in New York City. Some of his interests were hunting and fishing, having inherited an enthusiasm for the wilderness from his father, who was a close friend of naturalist John J. Audubon. Sometime in this period, most likely through his friends, the Livingstons, he apparently got to know Paul Smith, whose hotel was quite famous with New York City sportsmen, and he made his first trip to the Adirondacks. 5 After dabbling in the navy and brokerage firms as potential careers, Trudeau enrolled in the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York (now part of Columbia University), graduating in 1871. He married Charlotte Beare, daughter of a clergyman, in the same year. Trudeau began a private practice, first in Little Neck, Long Island (his wife's hometown), then moving into New York City where he was soon deeply involved with a private practice, clinics and classes in Manhattan.

Soon after the move, at the age of 25, Trudeau learned that he had contracted tuberculosis. The prescribed winter in Aiken, South Carolina did not help his symptoms, and his condition continued to decline. In the summer of 1873, a week after the birth of his second child, Trudeau returned to Paul Smith's Hotel as an invalid to spend his last days in the woods he loved so well. Leaving his young family, he said he was drawn "by my love for the great forest and the wildlife, and not at all because I thought the climate would be beneficial in any way." He arrived too weak to walk and yet after three months in the Adirondacks, he had improved enough to return to New York City with "the appearance of a man in good health." 6

Winter brought a relapse unrelieved by a move to St. Paul, Minnesota. He returned to Paul Smith's the following spring and summer. At the advice of Dr. Alfred L. Loomis, Professor of Medicine at New York University and himself a tuberculosis patient, Trudeau stayed on through the winter of 1874-75 with Paul Smith and his family. His symptoms continued to improve and the Trudeaus remained at Paul Smith's through the following summer.

When Paul Smith moved to Plattsburgh the following winter, Trudeau had to find another place to stay with his family. Unable to find suitable lodgings in Bloomingdale (a larger village at the time), he continued along the highway to Saranac Lake. Here he and his family rented the Reuben Reynolds house on Main Street. For the next six years, they boarded at Mrs. Lute Evans' house on Main Street, a place already "famous as a homelike and exclusive stopping place for sportsmen and invalids." 7

Doctor Trudeau attempted several times to move back to New York City, but each trip ended in a relapse. Hoping for a permanent cure that would allow them to return to the city, the family rented a winter place in the village for seven years, until finally building their own house in 1883 on the corner of Church and Main Streets. They continued to spend their summers in camp at Paul Smith's.

Until 1880, Trudeau hunted and fished in the woods as he was physically able. As he continued to recover, he slowly began to resume his medical practice. His personal physician, Dr. Loomis in New York City, began to refer patients to Saranac Lake to stay in the mountains under Dr. Trudeau's supervision. The presence of a doctor in residence was a benefit few other settlements in the Adirondacks shared, and it was a key factor in the development of the village as a health resort.

In 1875, the Berkeley House was built in Saranac Lake "for the accommodation of the city TB patients who were then beginning to seek the locality as a health resort, but for whose care there were neither suitable cottages nor hotels.8 Though having a capacity for only 15 or 20 guests, it was of ample size for all the demands then made upon it." 9 Milo Miller later described the Berkeley as "the first public house for the reception of invalids in the Adirondack mountains. " The building stood in the heart of the Berkeley Square Historic District until a fire destroyed it in 1981.

In the summer months, Dr. Trudeau would come down from his camp at Paul Smith's twice a week to see patients. He soon had quite a following.

"It was not long before the number would often be so large that they thronged his office porch and yard. The village had no suitable or adequate accommodation for them for a time, but with the building of the Berkeley and the enlargement or erection of houses and cottages expressly to care for invalids, provision was eventually made for all. By 1882 visitors had become so numerous, including many who could pay only a very moderate charge for care and treatment, that Dr. Trudeau determined, if funds could be raised, to establish a sanatorium for incipient cases at which charges should be less than actual cost." 10

In the summer of 1883, Trudeau suggested the idea of a semi-charitable sanitarium for the study and cure of tuberculosis to Anson Phelps Stokes, a New York banker who summered nearby at Upper St. Regis Lake. Stokes immediately contributed five hundred dollars to Trudeau's proposal. The St. Regis camp owners and their friends vacationing at Paul Smiths became the backbone of financial support for the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium. Dr. Loomis and other prominent doctors offered their professional support. Local guides and residents chipped in to buy sixteen acres of a sheltered hillside overlooking the valley and donated the land to Trudeau's new project.

Trudeau modeled his fledgling institution on one founded in Goebersdorf, Germany, in 1852 by Dr. Hermann Brehmer, who advocated a climatological treatment for tuberculosis, bringing patients to higher mountain altitudes where the combination of fresh air, exercise, ample rest, and good food could effect their cure. By 1884, only a handful of sanitoria were available for health seekers — and all of them were in Europe. Trudeau opened his Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium in February 1885 with the completion of an administration building and three small cottages, including Little Red," a one-room cottage with a small porch. Trudeau's first two paying patients, Alice and Mary Hunt, sisters who worked in a New York City factory, occupied "Little Red," a one-room cottage with a small porch.

For most of the nineteenth century, the term "sanitarium" was applied to all chronic care institutions. Coming from the Latin word ‘’sanitas’’, meaning health, its most common meaning is "health resort." Today it is most commonly the designation for mental health institutions because of its close etymological links with the word "sanity." By the early 1900s, however, a place for the treatment of invalids, particularly consumptives, was more often called a "sanatorium," from the Latin word ‘’sanare’’, which means to cure or heal. Trudeau christened his institution the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium in 1885. After his death, it was renamed the Trudeau Sanatorium.

Trudeau's establishment was the first successful sanatorium in America for the treatment of tuberculosis. The American Mountain Sanitarium for Pulmonary Diseases, opened in 1875 by Joseph W. Gleitsmann in Asheville, North Carolina, lacked major financial backing and had been forced to close after only three years. Trudeau's close ties with wealthy families vacationing at Paul Smith's assured that the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium did not meet a similar end. Individual donations and annual charity events consistently raised the money necessary to maintain the institution. Wealthy benefactors seemed more likely to underwrite the cost of a small cottage as their own individual gift rather than contribute towards a large institutional building, and (though tuberculosis was not yet known to be a communicable disease) Trudeau believed that aggregation should be avoided and more fresh air would be available in separate units.

Even as he opened the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium, Dr. Trudeau began to seriously study the disease of tuberculosis. At Christmas 1883, his friend, C. M. Lea, a Philadelphia medical publisher, gave him a complete hand-written English translation of a scientific paper, "The Etiology of Tuberculosis," written by Robert Koch in Germany the previous year. Its contents were a revelation for Trudeau and the world. Koch had discovered the tubercle bacillus, the bacterium that caused tuberculosis, and he showed that it could be identified under a microscope.

Fascinated by this radical new discovery and the potential which it brought of finally being able to identify both the cause and — with luck — the cure of tuberculosis, Trudeau attempted to replicate Koch's experiments. He returned to New York City that winter to learn how to stain and recognize the tubercle bacillus under the microscope. In 1885, Trudeau grew tubercle bacilli in artificial culture in Saranac Lake, the first scientist in America to do so. His makeshift home laboratory was the beginning of the Saranac Laboratory for the Study of Tuberculosis, Trudeau's second major institutional innovation, and the first scientific research laboratory in the united States devoted primarily to tuberculosis-related research. The Saranac Laboratory on Church Street, built in 1894, was the first lab in the United States designed for and devoted exclusively to tuberculosis research.

Trudeau's genius was his openness to ideas, applying and re-applying the newest in scientific thought to the pragmatic successes he had found in folk medicine, until he found explanations that made sense of his solutions. His European education and access to ideas through both the money and the connections of his wealthy and cultured friends were an unusual resource which he generously brought to bear on the problem of tuberculosis. Isolated as he was, he was also quite free to ponder new ideas, entirely unfettered by the politics of association with peers. the independence of his thought and his unrelenting determination were important qualities in the success of his research.

In his lifetime Dr. Trudeau was to receive a number of awards, including the first presidency of the National Association for Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, honorary American president of the International Tuberculosis Congress, and the prestigious title of President of the Congress of American Physicians and Surgeons. At his death in 1915, the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium was renamed the Trudeau Sanatorium in his honor.

In the summer of 1886, Dr. Trudeau devised a simple experiment which demonstrated the beneficial effects of climate, fresh air and ample food on the course of tuberculosis in infected animals. He infected a number of rabbits with the tubercle bacillus and then confined half of the infected animals, along with a control group of healthy rabbits, giving them a minimum of food, sunlight, fresh air and exercise. The rest of the infected rabbits were set free on a little island (now called Rabbit Island) in Spitfire Lake near Trudeau's camp. Here they ran wild in the open air with plenty of food and water.

After a period of time he examined the animals. The infected rabbits that were confined all developed tuberculosis and died, yet the healthy ones merely failed to thrive in confinement; they did not come down with TB. On the island, however, all of the rabbits thrived, despite their infection.

The results provided the proof which Dr. Trudeau had sought. First was the conclusion that bad conditions in and of themselves could not produce tuberculosis. His second and more far-reaching conclusion was that in the presence of tuberculosis infection, a subject's resistance could be directly affected by the environment. Fresh air, good food, ample rest, and moderate exercise could actually slow down or stop the progression of tuberculosis. Dr. Trudeau published the results of his experiment in July 1887 in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences and read a paper on the subject at a national meeting of the American Climatological Association that same year.

Trudeau's work was followed with great interest by the medical world, and his initial successes with patients were welcome beacons of hope for victims of the disease which had no cure. Popular literature extolled the health-giving virtues of the mountains, inspiring ever larger numbers to come to the Adirondacks. A handful of doctors regularly referred patients to Dr. Trudeau's care, and the number of health-seekers arriving in Saranac Lake steadily rose. However, the name of Saranac Lake first became nationally recognized as a health center in the winter of 1887-1888 when the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson came to the village to cure.

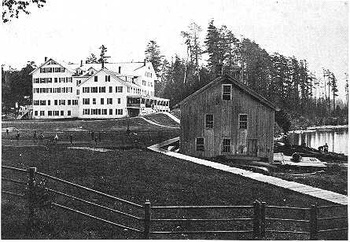

The Stevenson Cottage Recently catapulted to fame as author of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Stevenson came to America in 1887 in search of a better climate for his lung ailments. (Although it was never proved, Dr. Trudeau suspected he had an arrested case of tuberculosis.) Stevenson arrived in New York in September, too ill to continue to Colorado as originally planned. Local doctors recommended a winter in Saranac Lake instead, so Stevenson and his family rented quarters in the house of local guide Andrew Baker. Stevenson became Trudeau's patient and friend, and his health steadily improved throughout the winter. To Trudeau's despair, Stevenson's self-prescribed cure regime included chain-smoking cigarettes, writing in bed in a tightly sealed-up room, pacing on the rambling open veranda of the Baker cottage, and ice-skating on Moody Pond. Stevenson remained in Saranac Lake for about six months, leaving in mid-April for the South Pacific where he spent the rest of his life. The Baker Cottage (now called the Stevenson Cottage) still stands, a museum devoted to the author's life and works with the largest collection of Stevensonia in America, as well as headquarters for the Stevenson Society.

The Stevenson Cottage Recently catapulted to fame as author of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Stevenson came to America in 1887 in search of a better climate for his lung ailments. (Although it was never proved, Dr. Trudeau suspected he had an arrested case of tuberculosis.) Stevenson arrived in New York in September, too ill to continue to Colorado as originally planned. Local doctors recommended a winter in Saranac Lake instead, so Stevenson and his family rented quarters in the house of local guide Andrew Baker. Stevenson became Trudeau's patient and friend, and his health steadily improved throughout the winter. To Trudeau's despair, Stevenson's self-prescribed cure regime included chain-smoking cigarettes, writing in bed in a tightly sealed-up room, pacing on the rambling open veranda of the Baker cottage, and ice-skating on Moody Pond. Stevenson remained in Saranac Lake for about six months, leaving in mid-April for the South Pacific where he spent the rest of his life. The Baker Cottage (now called the Stevenson Cottage) still stands, a museum devoted to the author's life and works with the largest collection of Stevensonia in America, as well as headquarters for the Stevenson Society.

In this earliest phase of tuberculosis curing, invalids coming to the mountains stayed in hotels or in local homes with no special architectural arrangements to distinguish these buildings from any other houses. The rent-paying boarder usually had his/her own room and ate meals with the family, or, if bedridden, had meals brought to their bedside. Others, like Stevenson, rented larger quarters with kitchen privileges. The houses were typical mid-nineteenth century vernacular residences, often Queen Anne in style with porches or verandas primarily used by summer visitors. While these porches became important gathering places for curing patients, they had no special adaptations or features that would distinguish them from other porches typical of the time period and style.

Saranac Lake's Union Depot The management of a consumptive's cure was quite informal. The patient was enjoined to be outdoors as much as possible and encouraged to be active without overdoing it. Trudeau himself hunted and fished while curing, even though at times he was too weak to leave his guideboat and had to be carried from his hotel. A visitor in 1888 wrote of "consumptives in bright caps and many-hued woolens gaily tobogganing at forty below zero." 11

Saranac Lake's Union Depot The management of a consumptive's cure was quite informal. The patient was enjoined to be outdoors as much as possible and encouraged to be active without overdoing it. Trudeau himself hunted and fished while curing, even though at times he was too weak to leave his guideboat and had to be carried from his hotel. A visitor in 1888 wrote of "consumptives in bright caps and many-hued woolens gaily tobogganing at forty below zero." 11

Railroad passenger service to the village of Saranac Lake was completed during Stevenson's six-month visit, considerably improving accessibility. No longer did a journey to Saranac Lake include the lengthy forty-plus miles of rough roads from Ausable Forks. Now trains from Plattsburgh could bring visitors and patients directly to the heart of the village. The easy rail access, resident physicians, and the publicity which Stevenson's visit generated for the nascent health resort set the stage for an explosion of growth in the following years.

Footnotes

1. Philip L. Gallos, Cure Cottages of Saranac Lake; Architecture and History of a Pioneer Health Resort. Saranac Lake, NY: Historic Saranac Lake, 1985, p. 2. The original source for the "one in seven people" figure is Robert Koch, in a lecture given on the evening of March 24, 1882, in which he described his discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. See Robert Koch and Tuberculosis at NobelPrize.org

2. Ibid., p.25.

3. Frederick J. Seaver, Historical Sketches of Franklin County and its Several Towns. Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Co., 1918, p. 374.

4. Edward L. Trudeau, An Autobiography. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1915, reprint 1934)

5. Edith H. Shepherd, "Trudeau, The Beloved Physician," The Long Island Forum. February 1984, p.24.

6. Edward L. Trudeau, An Autobiography.

7. Donaldson, p. 232.

8. Per Phillip L. Gallos. However, the Registration Form for the National Register of Historic Places gives the year as 1876. Frederick Seaver gives the date as 1977.

9. Seaver, p.376.

10. Seaver, p.381.

11. Gallos, p.34.

IV. - The Architectural Development of the Cure Cottage

By the turn of the century, as climatologists claimed that the air of the Adirondacks was the essence of the success found by patients in Saranac Lake, local doctors began to alter the built environment to comfortably expose their patients to more air. At this time, the prescribed "fresh air treatment" was a well-regulated mix of bed rest, fresh air, and good food, basically allowing the body to heal itself. The average patient stay was about one year, and doctors were recommending that most of that time be spent resting outdoors.

Dr. Lawrason Brown, medical director for the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium from 1900-1912 and founder of the TB Society, was quite concerned about encouraging patients to spend more time in the fresh air and he insisted on "providing greater comfort out-of-doors so that the patient would enjoy living on his porch in all kinds of weather. "Brown was instrumental in a number of reforms in the physical arrangement of curing facilities in order to make the patient's outdoor experience more comfortable. He later published a book, Rules for Recovery from Pulmonary Tuberculosis, which included a number of specific recommendations on the subject of cure porches.

A good porch, according to Dr, Brown, should be well-ventilated but not drafty. Wainscoting around the lower walls helped protect against the worst winds, as did the walls of the house itself. Brown also recommended the addition of moveable glass panels to the upper portions of the veranda as windbreaks; glass panels were preferable to fixed or moveable canvas or wooden screens because they admitted the most light. Many cure cottage throughout the village display examples of verandas enclosed in this way.

Around 1900-1902, physicians at the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium began to experiment with increasing outdoor exposure, having patients spend the night as well as day in beds outside, only coming inside for short periods of time.

This was tried in some cases and under difficulties, but such good results appeared to be obtained and the outdoor sleeping seemed to be enjoyed so much by most of the patients that immediately steps were taken to make it possible to wheel beds direct from rooms to porches. 1

At Richardson Cottage, then (1902) under construction, work was too advanced to make room for patients to be wheeled directly from their rooms onto a porch, but the bedroom and main entrance doors were widened to allow beds to be wheeled through.

"After this no cottage was built at Trudeau or any patient housing provided without arrangements for direct access to a porch from the patient's roams." 2 Patients spent the night outdoors on their porches, then were rolled back in to the warm bedroom in the morning for a wash and breakfast. They would be rolled back out in the afternoon for the rest hours (2-4 pm), in again for dinner, then back out again for the night.

The private commercial sanatoria in the village were quick to follow the lead of the latest developments at the San, first enclosing verandas to better shelter their patients, then adding new cure porches from bedrooms on the upper floors. Existing structures were added to and enlarged as their clientele increased. The glass-enclosed cure porches used by tuberculosis patients are perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of the cure cottages built in Saranac Lake and elsewhere.

"An ideal sleeping porch, " wrote Dr. Lawrason Brown, "is one sufficiently wide for turning a bed, built out from the second story, with two sides that can be fully opened. It should not be too deep; the depth should not be greater than one and one-half times its width." 3

In nursing cottages for bedridden patients of this period, doorways onto cure porches are an average of 45-48-inches wide and there is no threshold. Often the flooring is continuous from the bedroom onto the porch. In many cottages, scratches and gouges can still be seen in the doorframes where the beds were rolled in and out. The doors were either paired French doors or oversized single doors, most likely constructed here in the village.

Because the porches were unheated, their parts expanded and contracted with the extreme temperature changes common in Saranac Lake. For this reason as well as for sanitary reasons (all patient spaces required regular cleaning and disinfecting), the interior walls were finished in tongue-and-groove beadboard paneling rather than plaster.

The windows enclosing the sleeping porch were usually large sliding glazed panels, often three-over-three; some rolled horizontally on inset casters. These also were probably custom made in village mills. By 1915, despite Dr. Brown's disapproval, some cure porches were being built with a row of double-hung sash windows instead. This may have been a less costly alternative, or it is possible that the local source for the larger sliding panels was no longer in operation.

Although glazed and furnished like a room, these cure porches were designed to be open to the elements. Protected from direct drafts, the patients were still outside in unheated spaces with windows open to the fresh air. Like other, more ordinary open porches, the floorboards often have a pronounced slope away from the house to promote good drainage and open slots or drain holes in the outside wainscoting to let out rain water or melted snow.

Another important feature of the sleeping porch, a call bell, reflected its medical function. Installed on cure porches and in patients' bedrooms, the bells were linked to a central house system, so a patient could summon the nurse to his bedside when needed.

The orientation of cure porches was an important consideration. '"The porch should face south by southwest in winter and north in summer, but a southern porch shaded well in summer by deciduous trees is usually very habitable. " 4 Sunlight was important for the psychological well being of the patient, but too much direct sun was also injurious for a person already battling elevated body temperatures. For this reason, canvas awnings were a necessity to be found on almost every residence and cure porch in the village, even long after they had fallen out of fashion elsewhere.

The Noyes Cottage, on Helen Hill

The Noyes Cottage, on Helen Hill

A simpler, more permanent solution was the planting of shade trees. Much of Saranac Lake had been completely denuded in the early years of the town by lumbering operations and farming; now property owners planted the hills with maples, elms, poplars and other species of shade trees.

As the curing industry expanded in Saranac Lake, contractors and speculators began to build houses specifically intended for use by persons curing from tuberculosis. Porches at the earliest stage can be classified as attached or add-on porches. Structurally, they are independent of the building core, abutting an exterior wall and covered by their own roof. As the title implies, they can be added onto an earlier- structure or they can be contemporaneous with the core building; in either case, however, they are a separate unit. The typical attached shallow-roofed cure porch over an open veranda is one of the most common types of cure porches to be found in the village. The Noyes Cottage on Helen Street is a classic example of the gradual accretions of attached cure porches that transformed so much of Saranac Lake's early housing stock.

Cottages built in the early twentieth century, after the advent of the sleeping porches, often show a more conscious incorporation of the cure porch into the structure of the house. The porch is structurally engaged with the main part of the building, with internal integration of its structural members. It projects from the core of the building but retains its own roof; it is distinct from the rest of the house, but not separate. The two-story wing with cure porch over cure porch is a common example of this type. The presence of engaged porches does not in and of itself indicate that the house was built as a cure cottage. Often only an examination of the internal structural members can actually reveal if the porches are original to the building or subsequent additions. The Lent Cottage at 18 Franklin Avenue has a representative pair of large, two-story engaged porches, and others can be seen throughout the Cottage Row Historic District and Helen Hill, as well as elsewhere in the village.

The third kind of porch that can be found in Saranac Lake is the inset porch. Here the porch is actually set into the body of the building, under the core building's roof and surrounded by its walls. It is an integral part of the structure, and almost always indicates that the building was originally conceived, designed, and built to function as a cure cottage. Inset porches are often quite subtle, showing the hand of a professional architect or master carpenter. For this reason, they are more often seen in the architecturally designed private homes of Highland Park, Glenwood or Rockledge. They are more rare among the commercial cure cottages of the village; by the time private sanatoria design had evolved to this, its most refined expression, the market began to decline and Saranac Lake's building boom slowed down. The unified form of Hopkins Cottage on 5 Birch Street and Finnigan's at 78 Main Street are perhaps the best local expressions of this type.

Footnotes

1. William H. Scopes, AIA & Maurice M. Feustmann, AIA, "Evolution of Sanatorium Construction," Journal of the Outdoor Life. May 1935, p.3.

2. Ibid.

3. Gallos, p.8.

4. Gallos, p. 12.

V. - The Second Boom (1918-1939)

A group of patients at Trudeau, 1919, from a photograph album kept by Verdo Newman, back row, second from left. Newman appears to have served in World War I and returned with tuberculosis. Courtesy of Lynn Newman. World War I brought a dramatic rise in tuberculosis cases around the world. In Europe, inadequate nutrition, poor living conditions and the stresses of war, as well as the gassing of soldiers on the battlefield, all wore down natural defenses against the disease. In America, increased screening of immigrants, refugees, and military conscripts led to the discovery of hundreds of incipient — and advanced — cases of tuberculosis. Many, like the Norwegian sailors who stayed at the Walker Cottage on Park Avenue, were sent to Saranac Lake to get well. Within a few years of the end of the war, 650 veterans were reported to be living in the village, and some 45 cottages had contracts with the Veterans Administration to provide care. 1

A group of patients at Trudeau, 1919, from a photograph album kept by Verdo Newman, back row, second from left. Newman appears to have served in World War I and returned with tuberculosis. Courtesy of Lynn Newman. World War I brought a dramatic rise in tuberculosis cases around the world. In Europe, inadequate nutrition, poor living conditions and the stresses of war, as well as the gassing of soldiers on the battlefield, all wore down natural defenses against the disease. In America, increased screening of immigrants, refugees, and military conscripts led to the discovery of hundreds of incipient — and advanced — cases of tuberculosis. Many, like the Norwegian sailors who stayed at the Walker Cottage on Park Avenue, were sent to Saranac Lake to get well. Within a few years of the end of the war, 650 veterans were reported to be living in the village, and some 45 cottages had contracts with the Veterans Administration to provide care. 1

By 1918 Saranac Lake had twelve to fifteen hotels, more than sixty boarding houses and twenty doctors, with a permanent population of about 5000. "An additional 1200-1500 health seekers, inclusive of accompanying relatives or friends and attendants" were temporarily in residence, "a floating population because continually changing in personnel, but not varying greatly in numbers." 2 A 1917 village survey map [Map #4] prepared by Forrest B. Ames, Health Inspector, shows over 520 buildings housing actively tuberculous individuals — almost half of all the buildings within the village limits.

Dr. E.L. Trudeau's gravestone, at St. John’s in the Wilderness

Dr. E.L. Trudeau's gravestone, at St. John’s in the Wilderness

The village of Saranac Lake continued to grow rapidly in the years after the Great War. Dr. Edward L. Trudeau, increasingly bedridden by his own tuberculosis, died in 1915, forty-three years after he traveled to Paul Smith's to spend his last days in his beloved Adirondacks. The Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium was renamed Trudeau Sanatorium in his honor, and, the following year, the Trudeau School was established as a national training program for medical personnel who worked with pulmonary diseases.

By 1918, the Trudeau Sanatorium had forty buildings in its complex on the side of Mount Pisgah, including an infirmary, library, central administration building and craft center. Nearly every building or improvement was a gift or a memorial. A team of ten nurses and five doctors were treating 300-400 patients a year with one out of every six or seven being completely cured. About 60% of the remainder found their symptoms either arrested or improved.

By 1920 the village population was over 6000, and the community included 753 private residences, 145 buildings "in which housekeeping suites are rented," one large modern apartment building, 85 boarding houses, and thirteen hotels. In the period 1920-1932, empty lots in the commercial district were filled with new construction.

Many of Saranac Lake's largest public buildings were constructed in the mid- to late 1920s: the Hotel Saranac, the Harrietstown Town Hall, Petrova School, Will Rogers Sanatorium, the "Santanoni Apartment House for Health Seekers" on Church Street, the National Guard Armory, and the Paul Smith's Electric Light and Power and Railroad Company building, as well as new bridges over the Saranac River on Broadway and Woodruff Street. All are large-scale, masonry structures comparable with those found in cities of far greater size. Most, however, are the work of local architectural firms such as Scopes & Feustmann and William Distin.

As many as three large commercial laundries were active in the 1920s to clean and sterilize patients’ sheets and laundry. Movie theatres, restaurants, speakeasies and taxicab companies all helped entertain the patients who were well enough to leave their cure porches for a visit to town. A curling rink, first built in 1918, was replaced in 1930 by a larger concrete building with a unique Lamella roof, again designed by William Distin.

A full range of cure cottages were available in the village to cater to every degree of illness. The changing addresses of a patient in the process of curing often charted her or his personal progress in the battle against tuberculosis ... or the state of their personal finances. Almost all patients made their own housing and medical arrangements based on their financial resources and their doctor's recommendations. If their cure was particularly difficult or lengthy, they would often try to move to less expensive cottages or to the subsidized sanatoria such as Trudeau San or Will Rogers Memorial Hospital.

Because of the level of attention required, nursing cottages were not as common as those for patients who were more mobile. "Up cottages" for patients well enough to be ambulatory were basically rooming houses or, if meals were served, boarding houses. Nursing cottages offered bed tray service or nursing care.

Eventually patients could improve enough to move into their own apartment or house, sometimes still hiring housekeepers or ordering meals from nearby cottages. Those who arrived with family members or attendants rented full apartments or houses with cure porches provided for the patient.

The psychological aspects of healing were considered an important part of the curing process, and for this reason, many cure cottages catered to specific nationalities and ethnic groups, or those who worked in similar industries. There were cure cottages for Greeks, Cubans, and blacks, kosher cottages for Jews, and other cottages for World War I veterans, vaudeville performers, and those who worked in the circus and the theater. Corporations such as DuPont and Endicott Johnson Shoes supported the operation of cottages in Saranac Lake to care for their employees who had become ill with tuberculosis, in this way respecting their obligations in the days before health insurance. Many patients first developed lung problems working in the debris-clogged air of factories, particularly in the textile industry. Leather-working industries also seemed to have a high percentage of workers who developed tuberculosis, most likely transmitted through tanned skins from tuberculosis animals. If caught early enough, tuberculosis could be put into almost permanent remission, but the disease never totally disappeared. If an ex-patient over-extended himself through stress or work, the tuberculosis could flare up again with disastrous results. Similarly, if the disease had advanced enough to seriously damage the lungs, or was a particularly fast-moving strain known as "galloping tuberculosis," the chances of recovery were slim.

Those patients whose health continued to deteriorate sometimes moved to the home of a sympathetic nurse to spend their final days in homelike surroundings. Their bodies were either shipped back to their families by railroad or they were buried in Pine Ridge or St. Bernard's Cemetery. A popular American slang phrase in the early part of the century, "a one-way ticket to Saranac, " spoke volumes about both the fame which Saranac Lake had as a center for the battle against tuberculosis, and the difficulty in beating the disease at a time when great numbers of tuberculosis patients never returned alive.

Because of public misconceptions about tuberculosis and its contagious nature, often patients were disowned by their family and friends. Even when their cure was declared complete, many chose to remain in the Saranac Lake area. Others like Trudeau found that they could not leave these mountains without suffering a relapse of their disease. The community benefited from the extraordinary talents of the many ex-patients who stayed.

Almost all of Dr. Trudeau's staff were either recovered tuberculous patients, or related to someone who had had it. Dr. Edward R. Baldwin arrived in 1892 to cure at the San; he eventually took over Trudeau’s tuberculosis research. Dr. Lawrason Brown, director of the San from 1901-1929, was another recovered patient. Many of the tuberculosis centers that opened in America between 1900 and 1930 were staffed by men who had studied and often, cured, in Saranac Lake. The prominent local architects William L. Coulter, William H. Scopes, and Maurice Feustmann all first came to the village as patients. Many of the later cottages were run by former patients whose cures had been successful. Even though their tuberculosis was no longer active, most former patients continued to use cure porches and follow the curing routine as a preventative measure for the rest of their lives.

The patient influx peaked in 1922, when more than sixteen hundred new patients came to the village, joining others who had been curing for two to four years and longer. Many were veterans of the First World War. The 1924 construction of Sunmount, a new curing facility operated by the Veterans Administration moved many of these men (and the associated jobs) to Tupper Lake after local doctors opposed its location in the village for a variety of reasons.

The pace of growth nevertheless continued through the 1920s, until the village reached its peak in 1931 with a population of 8000. By this time, medical experience had begun to show positive effects for the fresh air cure in any location, refuting the belief that it was exclusively the Adirondack air that restored health. Local counties throughout the state began to build sanitoria for local patients and the numbers of patients arriving in Saranac Lake began to diminish. New regulation requiring that all patients be housed in single rooms was in part an attempt to assure full occupancy in the cure cottages of the village.

The Stock Market Crash of October 1929 was a Black Friday for the cure cottage industry as well. As the bottom dropped out of the national economy, so too fell the number of tuberculosis sufferers who could afford the luxury of curing in the nation's premier tuberculosis curing center. Local sanatoria throughout New York State and elsewhere provided charity care, and experience had proven that with proper care, tuberculous patients could successfully cure in their own homes.

Trudeau Sanatorium continued to take in patients through the 1930s, eventually expanding into a complex of sixty buildings with a post office of its own, but the number of patients in the village slowly and surely began to fall. Almost no new buildings were constructed in town after 1932.

Patients continued to come to Saranac Lake from all over the world, however, and the village maintained its cosmopolitan nature throughout the twenties and thirties. Prominent citizens from Cuba, Puerto Rico, and other South American countries cured in cottages such as the Gonzalez Cottage in Cottage Row. Philippine President Manuel L. Quezon died of tuberculosis in a local cottage in 1944. Theatrical people, ball players, politicians and gangsters all spent time on the porches of Saranac Lake.

Footnotes

1. Gallos, p.19.

2. Seaver, p. 383.

VI. - Decline and Rebirth (1939-1990)

The Seeley Cottage

The Seeley Cottage  The Pomeroy Cottage The cure for tuberculosis, like the cure cottage, was constantly evolving as doctors sought new means for conquering the White Plague. During the 1920s, doctors in Saranac Lake began to try a variety of surgical techniques to help the lungs rest and thereby speed up the recovery from pulmonary tuberculosis. In 1944, the drug streptomycin was discovered to be effective against TB. By 1946 doctors had learned to combine another drug, PAS, with it in order to reduce the side effects. Patients recovered in half the time, and porches were no longer essential to the process of curing. By 1952, Isoniazid was introduced, displacing streptomycin as the drug of choice for treatment.

The Pomeroy Cottage The cure for tuberculosis, like the cure cottage, was constantly evolving as doctors sought new means for conquering the White Plague. During the 1920s, doctors in Saranac Lake began to try a variety of surgical techniques to help the lungs rest and thereby speed up the recovery from pulmonary tuberculosis. In 1944, the drug streptomycin was discovered to be effective against TB. By 1946 doctors had learned to combine another drug, PAS, with it in order to reduce the side effects. Patients recovered in half the time, and porches were no longer essential to the process of curing. By 1952, Isoniazid was introduced, displacing streptomycin as the drug of choice for treatment.

The final blow for the cure cottage and the end of the curing era, then, was this bittersweet discovery of antibiotics that were effective against tuberculosis bacilli. The triumph of medicine, aided by doctors and researchers in Saranac Lake, also meant the end of the Adirondack rest cure. With a dwindling number of patients, the Trudeau Sanatorium closed in 1954. Its buildings remained empty for years until the American Management Association acquired the complex in the 1970s. Many of the cure cottages in the village were converted to multi-unit residential use. Others were lost over the decades due to neglect and fires.

The Trudeau Institute, a biomedical research institution specializing in immunology, was established in 1964 to continue the work of the Saranac Laboratory. Tourism and recreation continue to be the most important sources of revenue for the local residents.

The extraordinary number of structures related to the curing industry which remain, and the integrity of their cure porches and other curing details, form an unique and important architectural record of an era, and a disease, that is now unfamiliar to most Americans. The identification and preservation of these structures is invaluable for the documentation and future interpretation of the impact of tuberculosis on this nation, its people and its architectural heritage.

Note: This article originally appeared here as part of a submission to the United States Department of the Interior, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

III. - Boom Time as a Tuberculosis Curing Center (1888-1918)

The population of the village of Saranac Lake in 1880 was 533. Eight years later when the first train arrived, it could still be described as a little backwoods settlement, in which log cabins were common, and venison one of the staples of diet. On the edge of the Canadian border and encompassed by a trackless country of woods and lakes which — was still called "the Adirondack Wilderness," it had in winter the isolation of an outpost of the snows. 1