Beanie BarnetBorn: February 20, 1886

Beanie BarnetBorn: February 20, 1886

Died: February 10, 1977

Married: Elizabeth Widmer Barnet

Charles Swasey Barnet, known as Beanie, was a patient at the Trudeau Sanatorium who launched a publication, the Trotty Veck Messengers, that would ultimately sell four million copies. Arriving in Saranac Lake in 1906 at age 21, he stayed at the Haase Block, the Benjamin Woodruff Cottage, Riverside Drive, the Johnson Cottage, Ledger Cottage, and a house on Old Lake Colby Road.

Center for Adirondack Studies Newsletter, Volume 2, Number 2, Winter-Spring 1980-81

Beanie Barnet and the Trotty Veck Messages

If, while sorting through old correspondence, cleaning your attic, or disposing of family papers, you should come upon a 16-page leaflet with a name like "Blessings" or Good Wishes," don't throw it away! You have come upon a Trotty Veck Message, a bit of Adirondack history, the unique product of its times and of Saranac Lake's fame as a treatment center for tuberculosis. As the inside front cover of each booklet explains: "The publication of the Trotty Veck Messages was begun in 1916 by two young men — two messengers of cheer — who were obliged to live in the mountains but who believed that the only way to conquer mountains is to climb — and climb cheerfully." The two young men were Seymour Eaton, Jr., and Charles Swasey Barnet.

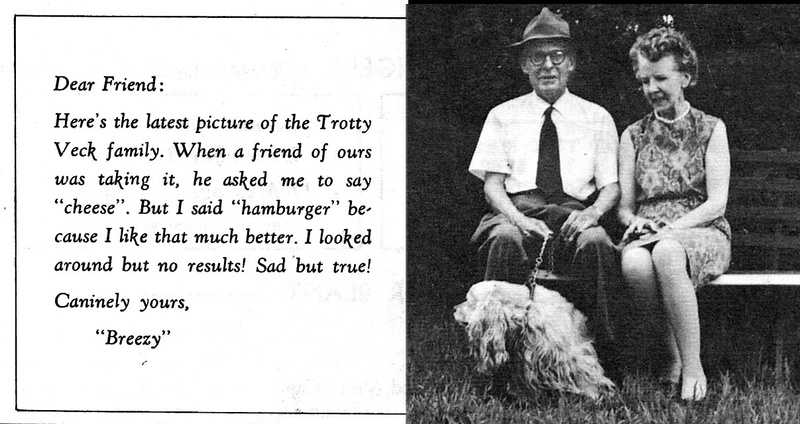

Beanie and Elizabeth Widmer Barnet, and their dog, Breezy.

Beanie and Elizabeth Widmer Barnet, and their dog, Breezy.

Historic Saranac Lake CollectionEaton was born in Lansdowne, Pennsylvania, and had been a student at Syracuse University. His father, Seymour Eaton, Sr., was famous as an advertising authority, the originator of the Teddy Bear craze, and of two circulating libraries that flourished in this country in the early 1900's — the Tabard Inn Library and the Book Lovers' Library. When forced by his health to attempt the "cure" at Saranac Lake, the son became the roommate, in a private sanatorium, of Charles Swasey Barnet, known in Saranac Lake as "Beanie" in honor of his Boston origins.

Beanie was the son of Robert A. Barnet, an extremely successful amateur playwright and businessman. His mother was Sarah Swasey Barnet, a member of the first class at Wellesley, who named her son for her father, a Union Army surgeon in the Civil War. A document signed by Abraham Lincoln, attesting to Dr. Charles E. Swasey's service, is a treasured family heirloom today. Robert Barnet, though born in New York, had come to Boston as a child. His own father, known as "Precise and Particular Barnet," had business that took him often backstage and into the company of writers such as Edgar Allan Poe. The character traits inherited from his father were credited with making a success in the theatre of Robert Barnet. As Beanie's former secretaries will tell you, they were his characteristics as well.

Robert Barnet was the author of several outstanding productions for the First Corps of Cadets in Boston, including "1492" (later Beanie's phone number in Lake Colby), "Pocahontas," "Prince Pro Tem," "Tobasco," and "Jack and the Beanstalk." Not only did he write the librettos for these musicals, but he also directed the rehearsals, designed the costumes and worked out the stage settings and effects. No ordinary amateur theatricals, his plays more than once made it to Broadway as professional productions. In "1492" Robert Barnet also played the part, to hilarious effect, of Isabella, "the daisy queen of Spain." At his death, more than one newspaper writer recalled that role.

The Barnets' must have been a household full of fun, financially comfortable, with four sons, and two daughters, intelligent and educated parents, famous friends. Beanie was a student at Boston Latin School, founded in 1635 and described as "an uncompromising bastion of academic excellence." A letter from the Headmaster in 1961, John J. Doyle, states: "The alumni records show that (Charles S. Barnet) entered Class IV in September 1901 and remained through Class II in 1904. He did not return for Class I and therefore did not graduate."

The alumni records state the facts, but they conceal a personal tragedy. At the age of 18, a young man with "prospects" — in that innocent America before the first World War — left school after his junior year and "dropped out." He dropped out of the life he had known, out of his circle of friends, away from the ocean where his family had summered. Tuberculosis was often a death sentence, especially for the young. Beanie was fortunate that his family could send him away to the mountains; many others not so well off died in the cities.

Beanie arrived in Saranac Lake in 1907, expecting to die. The leather-bound scrapbook filled with newspaper clippings of his family's activities show evidence of a home-sick young man. Meeting Seymour Eaton must have helped to alleviate that homesickness.

When word came from their physicians that neither Eaton nor Barnet would ever be able to engage in active work, the problem of earning a living became uppermost in their minds. Eaton's father — perhaps as much to occupy his own invalid as to cheer others — first conceived the idea of publishing inspirational messages. "There are thousands of people all over the world who are in need of a message of cheer. We will give it to them. If they can pay for it, fine. If they can't we will send it just the same." With this hearty and altruistic send-off, the business was started in the room Eaton and Barnet shared.

The name "Trotty Veck" was chosen from "The Chimes" by Charles Dickens. The first page of each Message explains why:

"Toby Veck was a messenger. He was called Trotty from his pace; a weak, spare old man; but a Hercules in his good intentions.

He loved to earn his money. He delighted to believe he was worth his salt. With an eighteen-penny message in hand, his courage, always high, rose higher; and he had perfect faith in his ability to deliver, no matter how difficult the errand or how complicated the route.

Trotty's headquarters were in a sheltered niche of a church wall, and his dearest friends—the inspiration of his life — were the chimes which measured off the record of his working hours. Wind and rain or a fall of snow only increased his courage, made him more anxious to be helpful in his calling as a 'common carrier.' Trotty was an optimist; a messenger of cheer. You and I can be messengers of cheer: we can be Trotty Vecks."

The choice of this passage can be read as a transparent metaphor for Eaton and Barnet's feelings about themselves and their situation. They were physically "weak," but strong in their "good intentions." They were young men snatched out of the world just at the point when they might have begun to produce, as their education had been preparing them to do; they were keen to be a part of that world. Each of them "loved to earn his money," "delighted to believe that he was worth his salt," and "had perfect faith in his ability to deliver." Their "headquarters were in a sheltered niche" indeed, a sanatorium bedroom.

Against all the odds, Eaton and Barnet became Trotty Vecks. Quotations were gleaned from whatever sources appeared in the pile of reading by the bedside. Publishers were written for permission to reprint. But in March of the same year, when the business was barely begun, the senior Eaton died. The entire operation was now the sole responsibility of the two optimists. The first year they sold 4,000 copies of "Good Cheer."

The next step was to rent an office in downtown Saranac Lake. Beanie was strong enough to visit the office for only an hour or two at a time. Eaton remained bedridden. They hired office help. Then in July of 1918, Eaton succumbed to tuberculosis.

Beanie was alone, an invalid, and responsible for a small business. Remarkably, he did not give up. He continued to search through his reading for uplifting quotations. The Saranac Lake Free Library keeps a box of his scrapbooks with clipped quotations from many sources, some original ones penciled in, many rewritten from other sources with more "punch." From these books, Beanie produced the series of Trotty Veck Messages which poured forth from his little offices. He began to receive not only orders for the Messages "ON APPROVAL," but also letters from those who had read them and been cheered. Not long after Eaton died. Beanie made one of his infrequent visits out of town. His doctor had discovered tuberculosis in one kidney. He went to Montreal to a specialist. The doctor told him he had a 50-50 chance: "I've done this operation twice. One patient was cured, one died." Beanie took the chance and dramatically improved the odds on that operation. His own strength grew. Responding to the challenge of helping others, Beanie helped himself.

Among those to whom the Messages brought hope were servicemen in both World Wars and in Korea. Framed and hung on the office wall was a tattered Message, covered with the mud of the trenches removed from the pocket of a U.S. Marine who had underlined some passages. Returned with his personal effects to the serviceman's mother, it was passed on to Beanie. Whether or not it contained the proverbial bullet hole is up to the beholder to judge.

Almost an entire scrapbook in the Library collection contains letters from World War II chaplains, thanking Beanie for the leaflets he had sent them. Often they were paid for by a few extra dollars enclosed as a donation with a regular order. Among those letters is this one, from Sgt. T. E. Howard, 32373681, Somewhere in Italy, 1 August 1944:

Dear Mr. Burnett.

I found the enclosed booklet in No Man's land in Italy. I thought I was the only man from Saranac Lake over here and I did not have the book so you can see that you have a good publicity agent somewhere in the world.

Very truly yours, Ted

The Messages Beanie was mailing out "wherever the postmen of the world carry their letters" remained in a standard format almost from the beginning. They were small enough to enclose in a regular envelope, about 3" by 6". They were always 16 pages long with the text printed in red and black in a variety of type styles. The covers were on heavier paper in many different two-color combinations, sometimes changed as the various numbers were reprinted. There were about 40 Messages in all, beginning with No. 1, "Good Cheer." Currier Press in Saranac Lake printed many of the Messages, in new issues of 100,000 each October. Many years, there was also a reprint order for 20,000 of another number. When offset printing became commercially available at Lane Press in Vermont, they began to do Beanie's work. His friend, Jim Finn, continued to handle the paper jackets with seasonal greetings, the custom imprinting for businesses and individuals, and Beanie's personal Christmas cards -a story in themselves.

Orders were seasonal, with advertising aimed at the Christmas trade. Usually, one secretary was kept on year-round, but in the peak years — according to Lil Spaulding, Beanie's neighbor and secretary — Beanie had "a big staff, seven or eight in the office" from September through Christmas.

According to the Adirondack Daily Enterprise, four million copies were sold by 1966, when publication ceased. From the beginning, they were sold in lots of two to 100. Customers ranged from those who inquired whether the mail from Saranac Lake was disinfected to Harry Houdini, who sent a check with his picture on it that was never cashed, but framed instead. Beanie's wall was covered with the evidence of his friendships with the famous, from Ruth Etting to Paul Whiteman and Christy Mathewson. His customers included Lowell Thomas, Lawrence Welk, Sally Rand, and Mrs. Billy Sunday. In Saranac Lake he became a close friend of the William Morris family and of their guest Harry Lauder, whom Beanie took fishing. A framed photo with this inscription was Beanie's memento of the occasion: "The next time ye tak me fishin, Tak me to where the fish iss and not where they wass."

Beanie had a little camp on Lake Clear and a guideboat made for him to facilitate his great love — bass fishing. He was a movie buff who, with Bill Petty, took reels of 16 mm wildlife and wilderness movies which they showed in the schools. His friendship with William Morris encouraged both his love of the stage and his civic-mindedness. He served as Morris's secretary when the theatrical agent was staging the benefits he sponsored for so many local causes. In addition, Beanie was secretary of many local organizations, including the old Board of Trade, the Speed Skating Association, the Rotary Club, the Pontiac Club, and the General Hospital. Truly the grandson of "Precise and Particular Barnet," Beanie kept meticulous records and was an exacting employer, once resetting his watch when Lil Spaulding was five minutes late to work.

For many years, Beanie conducted his business from the living room/office of the apartment he rented at 16 Academy Street. While living there, he met Elisabeth Widmer, a delicate Swiss-born graduate of the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, who had also come to Saranac Lake for her health. The story goes that Beanie had been airing his cocker spaniel of the time in his back yard and saw Elisabeth at the window of the adjoining Robbins cottage. A sociable fellow, he soon managed to meet her.

In the summer of 1940, when Beanie was 54, they were married. The ceremony took place in front of the fireplace at Camp Intermission, William Morris' summer home. In a rather breathless start to their married life, Beanie left from his home on Academy Street for the wedding, but returned with his bride to the "House by the Side of the Road." Located on the old Lake Colby Road, "two miles directly north from the Saranac Lake Post Office where friends of Trotty Veck are always given a warm welcome," the house was leased to the Barnets at a nominal rent by their friends the Morrises. It had once been used as a "tea room"/speakeasy known as The Silhouette. Used for a time by the local Catholic church, it was available when Beanie got married and needed to move his establishment from Academy Street. Lake Colby became Beanie's home for the rest of his life.

Behind the cedar hedges, Beanie and Elisabeth lived the disciplined life of those with arrested cases of tuberculosis. Good fresh food at regular hours, everything in moderation, fresh air and exercise, and the sacred rest hour from two to four in the afternoon were the requirements around which they built their lives. If the schedule seemed rigid to some, it seemed a vital necessity to the Barnets, who owed their lives to it. Within those restrictions, they lived an enjoyable life.

The Trotty Veck family always included a cocker spaniel; Toby, Yodel, Breezy, White Flash, and Peggy were some of them. They were always bought from a kennel in Vermont, which required an expedition, usually including a friend to drive. They lived with the company of flocks of wild birds which came to their feeders, and Beanie reported the temperature regularly to the Enterprise. The business was carried on in Lake Colby, as it had been on Academy Street, from Beanie's combined living room/office.

As time passed, the distinctions between home life and the business blurred, and secretaries took on more homely duties. Optimism went out of fashion, and sales of the Trotty Veck Messages, which had at one time earned Beanie a handsome living, waned. In 1975 Jim Finn printed Beanie's last order of Christmas cards. Charles Swasey Barnet died a peaceful death at home in Lake Colby with his wife on February 10, 1977, aged 90. His obituary states that he came to Saranac Lake "for his health," a euphemism for tuberculosis, in 1907. It is a tribute to his own unfailing spirit that he should have lived so long and so well under the sentence of death, that he should have made so much of the restricted life allowed him.

A quotation from one of his notebooks fits Beanie very well: "Thou comest not to thy place by accident - 'tis the very place meant for thee."

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, August 26, 1995

Discovering family photos while visiting Saranac Lake

By ALISON BARNET Special to the Weekender

(Editors note: Alison Barnet is a teacher and writer who lives in Boston.)

SARANAC LAKE - It started with a casual comment: "These porches remind me of the porches of Saranac Lake."

Frankie Schmidt, a friend of a friend, was making conversation as we drove around Boston shortly before Christmas.

Saranac Lake was a familiar name from my childhood. Great-uncle Swasey — known to Saranac Lake as "Beanie" because he came from Boston - had lived there. I'd never met him, nor did I know much about him, but that was about to change. Frankie put me in touch with some people and soon I was planning a trip.

I had been doing research on my great-grandfather, Beanie's father, known to 1890s Boston as the "Extravaganza King." He wrote popular amateur shows and played a stunning Queen Isabella in "1492," his biggest hit. His fortunes took a dive early in the new century, however. One setback was that his oldest son. Beanie, at 21, contracted TB and had to be sent away, probably to die.

Swasey Barnet arrived in Saranac Lake in 1907. Instead of dying, he lived to be 90. Over the next 70 years, he became a Saranac Lake fixture - publisher of the inspirational and humorous Trotty Veck Messengers, close friend of the William Morris family and their guests, and active member of civic and outdoors groups.

I visited Saranac Lake in July. In addition to Beanie's old Lake Colby Road home, the Adirondack Room and many other sites, I went out to Maxine Summers' antique place in Vermontville. Maxine brought out several boxes for me to see.

In a folder of old photographs, I was surprised to come across a picture of my grandmother. Next I discovered my great-grandfather (the playwright), aunts and uncles and their children, my father at age 2 — all dating from the 1920s. One after another the familiar faces of my family jumped out at me, faces that wouldn't mean much to others. As family members married and had children, they had sent photos up to Beanie. Here I was discovering them in 1995!

In another box was a collection of Boston play programs, abruptly ending in 1907, in others wedding invitations, negatives and photos of Beanie in his early years in Saranac Lake.

A stern 1905 letter from his grandfather was stuck among the invitations: "It has been impressed upon me that money burns in your pocket," he wrote, warning that success was threatened by "your passion for amusement." A fascinating pre-TB portrait emerged of a wealthy, carefree young man, avid theatre-goer and lover of the social life. How interesting that his life in the Adirondacks turned out. in its way, just as social and full of theatre. How proud stern grandpa would have been of his success.

Back in Boston surrounded by Beanie's prized possessions, I quote a Trotty Veck Message: "Don't worry because the tide is going out — it always comes back."

Lake Placid News, December 14, 1922

"TROTTY VECK MESSENGERS" RECEIVE GENEROUS RESPONSE

Members of the senior class of the Saranac Lake high school, who for the past week have been selling "Trotty Veck Messengers", C. S. Barnet's harbingers of good cheer, in order to raise funds to finance the proposed trip to the National Capitol during their Easter vacation, report that nearly a thousand copies have been sold,

Mr. Barnet is assisting the class by furnishing the books at cost for this particular sale, and is also offering prizes to the teams selling the most books.

The Messengers are furnished with appropriate wrappers making them suitable for use in place of a Christmas card. The entire set is furnished in a special case, also attractively designed.

Girls of the class have been particularly active in the sale of the books, and report a generous response throughout the village.

Copy of a brief manuscript written by Elise Chapin, dated September 1, 1990

Charles Swasey Barnet, known to the town as Beanie, came to Saranac Lake to "cure," and cure he did for he spent 70 years here until his death at age 90. Beanie was well known for his "Trotty Veck Messengers." Trotty Veck was a Dickens character who "trots" around delivering messages of good cheer. Publications of the messengers ceased after 4 million copies were distributed. A series of honey colored cocker spaniels, "Flash," followed Beanie everywhere through the years. He loved the outdoors, birds, fishing and his community.

Old Beany

by Henry Larom

In a time of trouble

Beany was my psychiatrist.

Into his boat of an afternoon

He put two plug casting rods,

A net,

Two sandwiches

A small pointed roof

Under which he placed

His caramel-colored spaniel.

He added one mason jar for personal relief,

Two cans of beer,

Two big cigars

And me.

Out on the quiet water

He taught me casting

Until my thumb controlled

The line so well that

I could drop the bait

Between two lily pads

At over thirty feet.

Dark woods surround that pond,

And nature rests there easily,

Held by a bass snapping at an insect,

By a woodpecker rattling against a distant pine

And the glitter of sunfish in the shallows.

It pulled me back,

Bending me, like a rod tip,

Back to where man, the animal,

Could concentrate

The way a cat does,

Patient, guileful and, above all, content.

The sun sank through orange-tinted water.

A breeze rose for a moment

Riffling waves against the bow.

Old Beany used the mason jar.

We had supper,

Sipped our beer

And lit up our cigars.

Frogs grunted in the twilight.

A wood thrush blew low flute notes to us,

And we felt part of pond, of bird

Of little skating water bugs and lily pads.

That was Beany's therapy,

And once in a while

We even caught a fish.

See also: Trotty Veck Messengers

Sources

- McLaughlin, Bill, "'Beanie' Barnet in his 90th year", Adirondack Daily Enterprise, Febrary 19, 1976

- The Discourse of Disease: “Patient Writes” at the “University of Tuberculosis”, p. 18, 19

- Information provided by his grandneice, Ann Alison Barnet, 2009.

- Barnet, Anne Alison, ''Extravaganza King: Robert Barnet and Boston Musical Theater.