Undated, unidentified clipping in a scrapbook at the Saranac Lake Veteran's Club.

Undated, unidentified clipping in a scrapbook at the Saranac Lake Veteran's Club. Undated, unidentified clipping in a scrapbook at the Saranac Lake Veteran's Club.

Undated, unidentified clipping in a scrapbook at the Saranac Lake Veteran's Club.

This photograph was published a third time, with a caption reading "Aviation Student Forrest Morgan, who is in Saranac Lake on furlough from Maxwell Field. Ala., where he is stationed with the U. S. Army Air Forces. He has been in service with the U. S. Army for the past year and was recently selected for aviation training." Forrest Morgan (Adirondack Daily Enterprise, June 6, 1989

Forrest Morgan (Adirondack Daily Enterprise, June 6, 1989  Tuffy Latour and Forrest Morgan

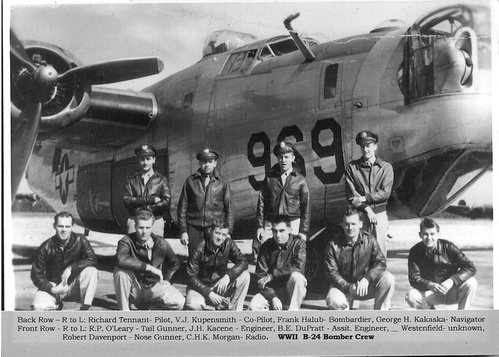

Tuffy Latour and Forrest Morgan  Forrest Morgan, front row, far left, with WWII B24 Bomber Crew. Photo courtesy of Josh Hummel

Forrest Morgan, front row, far left, with WWII B24 Bomber Crew. Photo courtesy of Josh Hummel  Forrest Morgan, front row, third from left with WWII B24 Bomber Crew. Photo courtesy of Josh Hummel

Forrest Morgan, front row, third from left with WWII B24 Bomber Crew. Photo courtesy of Josh Hummel  A memorial to Dew Drop Morgan at the Harrietstown Town Hall, November 13, 2012. Photo courtesy of Mayor Clyde Rabideau. Born: August 16, 1922

A memorial to Dew Drop Morgan at the Harrietstown Town Hall, November 13, 2012. Photo courtesy of Mayor Clyde Rabideau. Born: August 16, 1922

Died: November 10, 2012

Married: Sheila O'Reilly Morgan

Children: John Forrest Morgan, Terrence Morgan, James P. Morgan, Casey Kathleen Morgan Eurich, Dermott Morgan, Kelly Ann Morgan, Colleen Morgan, Bridget Morgan, Sean Morgan, Bryan Morgan, Kevin Morgan

Forrest "Dew Drop" Morgan was a son of Wilbur Morgan. He was a champion bobsledder and Olympic Bobsledding team manager, a World War II veteran, and the owner of the Dew Drop Inn at 36 Broadway which he operated for 42 years. He retired, selling the Inn in 1988, but, finding that he missed bartending, he took a position at the Lake Placid Lodge in 2000.

He was manager of the U.S. Olympic and World Bobsled Team four times and served on the U.S. Bobsled Board of Directors. 1

He lived at 72 Park Avenue in 1948, 8 Fawn Street in 1954, and at 191 Broadway in the 1960s.

From an article by Howard Riley in the Adirondack Daily Enterprise, October 11, 2003

Dew met his bride, the beautiful Sheila O'Reilly, in 1945 when she came here from Montreal (Westmount) to work at Dr. McDougall's camp.

He was born in 1922 on the Fitzgerald farm which his father managed. The barns and house occupied both sides of the Harrietstown Road near the Harrietstown cemetery on state Route 86. He was one of eight children: Leonard, Harold, Jerry, Anna, Ethel (Cushman), Lillian (who died at age 4) and Helen (Munn).

The nickname "Dew Drop" was given to him in high school by Murph O'Donnell as a way of teasing him by saying "You're as fresh as the dew on the grass." Dew says Murph must have been studying Shakespeare.

He served for one year (1946) as an officer with the Saranac Lake Police Department.

He bought the Bridge Bar & Grill from Max Shapiro in 1947 and changed the name to the Dew Drop Inn.

He was drafted into the Army Air Force in December 1942 and was discharged on July 6, 1945. He was called into service from the reserves during the Korean War but did not go overseas.

A very special bomber

His basic training was in Miami Beach (where they actually drilled on the beach). He then went to Aerial Gunnery School at Tyndall Air Field in Panama City, Fla. He trained in Lansing, Mich. and Charleston, S.C., and was assigned to the crew of a B-24 Liberator Bomber. There were months of training missions in the United States before his group went overseas. He was the armorer responsible for loading the armament including the bombs. (There were more B-24s built than any other American aircraft. It carried 10, 50-caliber machine guns, 8,000 pounds of bombs, could cruise at 175 mph, had a range when fully-loaded of 3,000 miles and was powered by four, 14-cylinder Pratt and Whitney engines).

The light beams of publicity would seek him out at an early age and shine on him from the most unexpected places. When his crew was ready to go overseas, they were given the 5,000th Liberator Bomber manufactured in San Diego, Calif. A photo of the plane is carried on an Associated Press picture page with Dew and the crew lined up atop the plane. The fuselage of the plane is totally covered with the scrawled signatures of the 7,000 employees who built the plane, and it is dubbed the Grand V and Sherman Billingsley, owner of the famous Stork Club in New York City, who hosted the crew for dinner.

He bails out twice

It was well documented in an Enterprise story only a couple of years ago about Dew and his crew being shot down, but I will recap that story so I can tell you about the second time that Dew Drop bailed out.

They flew the famous Grand V to their base in Bari, Italy, where they became part of the 15th Air Force. They were shot down on their 18th bombing mission over German-occupied Poland. The Grand V was in for maintenance and was not the plane that crashed. They were hit by anti-aircraft fire and were attempting to land in a Russian-held area of Poland. The No. 2 engine was on fire and the gas line from the booster tank to the main tank was leaking. When they saw what they thought were German fighter planes approaching, they fired red and green flares to signal a surrender but then discovered they were Russian YAK 9's, and the Russians opened fire on the crippled plane. Five of the 10-man crew were wounded, the tail gunner Perry Bailey suffered the most serious wounds. (Perry, from Troy, Pa., remained friends with Dew Drop after the war and had visited the Morgan family at their camp on Lake Clear.)

Dew Drop, a waist gunner, cranked up the turret of the belly gunner before he bailed out. He landed alone but rejoined some of the crew when the Russians picked him up and brought him to a mansion they were using as a headquarters. Other members were taken to other locations. Dew Drop and some of the crew were flown to an American base in Cairo, Egypt, where they were told during the debriefing not to tell about the Russians firing on them. The men all survived the attack and the bailout.

Dew volunteered to go back flying, but on his third combat mission the landing gear would not open as they approached their base. He had seen a B-24 belly-land when the sparks caused it to explode, so when the pilot gave permission for the crew to bail out, he was the only one to jump. The landing gear eventually came down, the plane landed safely and the MP's had to go pick up Dew Drop from the hillside vineyard where he had landed.

The 11 Morgans are Jim, John, Terry, Sean, Kelly, Colleen, Bridget, Brian, Kevin, Casey and Dermott. Sheila died in 1988. Jim and Kevin are also deceased.

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, November 10, 2001

Shot down by mistake

'Dew Drop' Morgan remembers the Russians who hit his plane

By PETER CROWLEY Enterprise Staff Writer

SARANAC LAKE -"They told me not to say that the Russians shot me down," said World War II veteran Forrest "Dew Drop" Morgan. "They told me that we weren't to breathe nothing about that."

It was fall 1944, and Morgan was at a U.S. Air Force base near Barie, Italy. He had just been released by his Soviet captors after they blasted his B-24 Liberator to the ground, reportedly thinking it was German. Now he was being interrogated by an American intelligence officer.

This Veterans Day, Sunday, Nov. 11, the Saranac Lake Veterans of Foreign Wars will cite Morgan for "outstanding work for the VFW." While many remember Dew Drop as a veteran, they more often think of him as part of Saranac Lake's local color.

Dew Drop is, if nothing else, a legend here. It's partly his reputation, as the "Yankee Dipper" who used to "walk the plank" into the Saranac River whenever his beloved Yankees lost the World Series. (He turned on the Yanks in the 1960s after what he considered their shabby treatment of slugger Roger Maris). It's partly because actress Faye Dunaway waited tables at his Broadway restaurant, the Dew Drop Inn, while working her way through college. It's partly because of the 11 kids he and his stalwart wife, Sheila, reared. It's partly because Dew was a champion bobsledder and Olympic Team manager who later lost one of his sons in a bobsled accident. It's partly his recent notoriety as a garrulous bartender at the Lake Placid Lodge.

But before all that, it was his war stories.

The gag order

The order to keep his mouth shut frustrated the 19-year-old Morgan. The Allies were trying hard to strengthen fragile ties with Josef Stalin and the USSR as the war ground to a close, but Morgan didn't know about all that. He wasn't even fully sure of what was going on around him (he would soon be diagnosed with shellshock), but he knew who had gunned him down, and it wasn't the Nazis.

But that's what the U.S. military told the press. The Adirondack Daily Enterprise reported around that time that a German fighter had shot down Morgan's plane. Morgan, however, had a more incriminating story on the Soviets than just that they had shot down his plane. During his short stay in captivity, he had heard through the Polish underground that it was the Soviets — not the Germans, as was believed in the States — who had rounded up and slaughtered 4,000 Polish officers in the area known as the Katyn Forest.

When Morgan would tell this story later to friends in Saranac Lake, they often doubted him. He even got to doubting his own memories. It wasn't until 1992 that he was sure, when he encountered his pilot from that mission, a prairie man named James Ayers who is now deceased.

"I said, 'Send me your version of what happened,' and he did and it was the same as mine," Morgan said, "that gave me a formation that it wasn't only me."

The way I recall it…

"The 13th of September, we took off on that mission" Morgan said. "We were bombing the Osweicim oil refineries in Poland."

In Ayers' letter, he noted that the crew was instructed to keep their bombs away from a "labor camp" near the refinery, they later found out that this camp was none other than the Osweicim (aka Auschwitz) concentration camp, where many thousand Jews were being slaughtered.

"We were hit, by flak," Morgan remembered. "We weathered that, and after we completed the bomb run, it's SOP, standard operating procedure, to transfer fuel from our bomb tank to our main tank, but the lines were cut because of the flak. . . . We only had a little fuel in the main tank. We knew we couldn't go back over the Alp Mountains, We knew we'd never make it. . . . I remember, saying, 'Let's go to Switzerland because that's a neutral country,' and I remember them saying, That's too far.'"

Two engines were also dead, so Ayers and the navigator set a course for a place that had been deemed safe for emergency landings when the crew was briefed in Italy. They were losing altitude, however, so they decided to land in Russian-held territory about 60 miles east of Krakow.

It was then that the Russian fighters showed up.

"I remember what they were; they were YAK-9s," Morgan said. "The standard procedure if you're going to give up, we fired and green flares and dropped our landing gears: We came in and we thought the Russians were going to escort us. And then all at once, they turned on us, and they started shooting us. Everything started exploding all over the ship.

"I don't remember if anyone gave the order to bail out. We all ended up bailing out. I even saw our plane go down in a field and I saw it blow up before [it hit] the ground. While I was hanging in the air, I only saw a couple other chutes, but they all got out.

"When I got down I landed on the ground, I figured we were in Russian territory, and I got unhooked from my chute and so forth, and along come some people on horseback and they were Russians. I had my hands above my head naturally, and I think they thought we were Germans.

"I was taken to some headquarters house and started to get interviewed, and I finally convinced them — I was one of the ones that convinced them — that I was American."

An underground informant

Once the Russians realized the crew was not German, they began making arrangements to return them to their countrymen. Meanwhile, over the three or four days Morgan was detained, he got to know the Russian's English interpreter, Nikolas, a retired schoolteacher who had become a lieutenant.

"I asked permission from this Lt. Nikolas, I said I would like to go to church," Morgan said. "He sent a couple of Russian guards with me, and we went to the church. I understood the Mass very well because I was an altar boy when I was a kid; everything was in Latin. . . . We were going out of the church with these two guards, it was crowded, and somebody nudged me and spoke to me — he spoke good English — he whispered, 'Tell them you want to go to the mill.'"

Curious, Morgan found out the mill was for making bread, and when he returned with the guards, he asked Nikolas if he could go there.

"He sent me with those two guards again to this mill, Morgan said. "I went to the mill, and this guy who bugged me in church, he started speaking to me in English. . . . I said to this guy, 'They (the guards) can hear you,' and he said, 'They can't understand English.' . . . He was saying to me, 'The Germans didn’t kill those 4,000 soldiers at the Katyn Forest,' . . . and then he gave me some notes, some addresses. I can remember they said Minnesota and Wisconsin, there must have been some Polish people who were there.

The man explained that the Polish army, having already been thoroughly beaten by the Germans, surrendered when the Russians moved in. The new occupying army, however, collected 4,000 of the best Polish soldiers and executed them by firing squad. Then, in Stalin's process of double-crossing the Nazis, the USSR blamed the massacre on Germany.

Morgan stashed the addresses, and soon he and his compatriots were aboard a Russian plane on a 600 mile flight to Poltava, an American shuttle base. From there, an American plane flew them to Payne Field in Cairo, Egypt.

Back at the base

From Payne Field, . . . we were flown back to our base in Italy, which was near Barie," Morgan said. "Then I was interrogated by, I guess it was an S-2 Intelligence. Whatever happened in it all, my American officers were kind of dumbfounded by my story, especially my story that the Russians had done that slaughter in Katyn Forest. That was unheard of in the USA then. The Russians were our close, close ally. They could do no wrong.

"Of course, being a kid, I was half in shock as well myself. I was mad afterward that I gave those notes with those addresses to my American superiors. I tried to get them back afterward, and I never could. . . . I hadn't memorized their names or nothing.

"I went back flying, I flew about two missions, and the pilot in the new plane I went onto suggested that I was little bit shellshocked. I flew a couple of missions, but it was his observation that I should go back to the hospital. I was in extreme psychoneurosis right then — shellshock —and they sent me home, sent me back to the States. . . . They even gave me a choice of different hospitals I could go to —rehabilitation hospitals. One was Plattsburgh, New York. Naturally I took that. It was the old Plattsburgh Air Force Base. Of course I got a discharge, then, July 6, 1945, and I got pronounced alright.

—Some justification

"After the war, I came back home here, and I didn't ever talk about this at all. When I did start telling people around here, confiding in them, they didn't know if I was telling the truth or not. . . . I sometimes would wake up in the middle of the night and wonder if all that had happened to me or not."

Morgan felt somewhat assured, however, by a German General's testimony he saw on television shortly after the war.

"When they had the Nuremberg War trials, I was watching it on TV. Naturally I was very interested," he said. "(This general) pleaded to I don't know how many charges, several charges of atrocities. He said afterward, I've proven to everyone that I'm not a liar,' and then he pointed over at those Russians and said, 'They're the ones who killed those people in Katyn Forest.' . . . That Russian delegation, when he made that charge at them, they got up and left the room."

At that point, Morgan said, the German general produced documents to prove that the Russians had committed the massacre.

Morgan felt justified, but for those who hadn't seen the trials, the story of Nazis massacring Poles in Katyn Forest was too ingrained to dispel. To this day, he said, some of his friends in Saranac Lake probably think he was making it all up.

Whether young men and women will return from Afghanistan with such stories is anybody's guess, but at the very least, they, too, will be honored on Veterans Day when they come home.

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, June 15, 2002, reprinted from September 1976

Holy Toledo and other expletives – baseball traditions

Are the great days already dead? Did baseball in Saranac Lake expire with Larry Doyle, Doc Sageman and Chuck Pandolph? There are a lot of whats and whiches to be answered here and soon.

The insipid 70s resurgence of the New York Yankees has not brought about the expected cry of "Allah be praised" from the home of the Number One Bronx Bomber fan in all fandom.

Dew Drop apparently reached a sub-zenith in his arc through the publicity heavens with his Esquire appearance and has now decided to die in peace. Hard to believe, of course, but quite obviously true!

Whatever happened to curb the sporting instinct of the once proud restaurateur is hazy, but the man who blithely tossed free wieners to a happy cheering mob as the Yankees connected for home runs is in state of inertia.

His sun is setting in an aura of mystery to most of us who witnessed the famous 1950s river bath episode when he walked the plank as bugles sounded taps and series bet was paid in icy October waters under the Broadway bridge.

Habitually, there was invective and scorching commentary weeks before the Yanks were crowned American League kingpins during their long reign of terror, and taking bows right along with Casey Stengel would be Dew Drop Morgan who never faltered in his blind belief that the Yankees were destined by God to Stay blessed and to perch on top forever.

Dew Drop's bistro carried the Yankees banner behind the cash register year-round, and there was just as much loyalty inspired during the spring training routine as in the waning weeks of summer when baseball fever swept the community — with the hub, of course, at Dew Drop Inn.

A reference to some time worn incident is resurrected in an old column forwarded anonymously by someone who misses the great World Series agitation and possibly the free hot dogs.

It says "Dew Drop Morgan is building some kind of barricade or L-shaped partition between his bar area and juke box and steak tables. So far, nobody has been able to put their finger on the logic behind this architectural gambol.

"'Doc' Sageman, a violent and rabid Red Sox rooter, inquired the other day if it was a fireworks frame to celebrate the possibility of the Yankees scoring a run this season."

Following the October river bath the year before, Dew Drop had acquired the title "The Yankees Dipper," and to top it off, thieves had absconded with his treasured Yankee banner. A reward of $25 had been posted for its return and it was believed to be resting in a nearby bar where it was occasionally spat upon in a sprit of derision.

After Doc Sageman's barb had settled into the Yankee rooter's epidermis, another piece in the Enterprise gossip column led off, "Nothing so upsets the famous Yankee Dipper as impolite references to his star studded stumble- bums. No ... Dew Drop is quite likely constructing a king-sized bulletin board to post the press notices of bush pilot Casey Stengel's faltering fumbers."

So you see, it was an armed camp around the village at World Series time. No longer is heard the hornet-like intensity of the razzberry hurled at the heart of the enemy. Spell it "Phrrp!"

The answer may lie in Dew Drop's reluctance to herald the striped shirts as World Champions before they have passed through the crucible of playoff activity, but this was never considered much of a deterrent before, and Dew was the first to admit it … even to capitalize on it!

If the free wiener gimmick is to surface again ever, the time to beat the drum is now. Dew Drop bears no malice for slights suffered in other eras. His unwavering loyalty to the classless Yankee editions of recent years makes one weep softly in retrospect, but if 1976 is to be remembered as more than just a Bicentennial year in Saranac Lake, it is time to prod the lion into some kind of fighting stance.

Ticonderoga Sentinel, May 28, 1931

Saranac Boy Bit in Battle With Reptile

Saranac Lake— As the result, of a battle with a snake, Forest Morgan, eight, son of W. T. Morgan of Harrietstown road, is under the care of a physician. The boy told his father that as he was playing in the grass near his home the snake struck at him and seized him by a finger, clinging until the boy trampled upon the reptile.

As there were distinct wounds in the finger, the father at once summoned Dr. Rae L. Strong of this resort, who now has the child under observation for symptoms of poisoning. It is believed that the snake was not of the poisonous type, as there are no true vipers in this section.

External links:

Comments

2010-08-04 10:44:21 August 2010: Dew Drop is reportedly conspiring with Hoot Sullivan to "escape" from Uihlein Mercy Center. —74.78.178.27

2012-11-12 08:00:05 A sad world without dewdrop. —71.164.105.5

2013-04-12 20:24:06 My father was the Perry Bailey that was part of Mr. Morgan crew. I had been to the Drew Drop Inn when Dad had visited the Morgans. I have the pictures of the crew on the wing of the V Grand,one with the whole crew on the ground with another plane that wasn't the V Grand and the whole crew at the Stork Club. My dad passed away in Aug 1997. I am sorry for the loss of Forrest as I remember him as kind man that like to make you feel at home. Remember his wife Sheila fondly.My dad never talk about the war so I found out alot with this sight. —72.18.63.244

Footnotes

1. Adirondack Daily Enterprise, June 6, 1989, p. 1