Dr. E.L. Trudeau was an avid hunter. In chapter XI of his autobiography he wrote, "My dogs were always a great pleasure to me and if I was ever tempted to extravagance it was in the purchase of a noted hound." He named three of his favorite hunting dogs: Bunnie,Scream and Watch. Ironically, the lap dog with which he is pictured here, in an unusually casual pose, was a Pekingese named Ho-Yen. "Lying on a soft bed suited him admirably, and a master who was always in bed was, to his mind, the kind of master to tie to. For the past five years I have never moved without this absurd little play dog. I never saw anything incongruous in doing so until one day last winter, wrapped up in furs, I sat in the sleigh with the little fellow in my lap as usual. Billy Ring, one of my old hunting guides, walked by. He stopped, and taking his pipe out of his mouth nodded at the little dog and said, 'Have you come to that, Doctor?'" Photograph No. P82.33 courtesy of Adirondack Research Room, Saranac Lake Free Library. Adirondack Daily Enterprise, April 26, 2014

Dr. E.L. Trudeau was an avid hunter. In chapter XI of his autobiography he wrote, "My dogs were always a great pleasure to me and if I was ever tempted to extravagance it was in the purchase of a noted hound." He named three of his favorite hunting dogs: Bunnie,Scream and Watch. Ironically, the lap dog with which he is pictured here, in an unusually casual pose, was a Pekingese named Ho-Yen. "Lying on a soft bed suited him admirably, and a master who was always in bed was, to his mind, the kind of master to tie to. For the past five years I have never moved without this absurd little play dog. I never saw anything incongruous in doing so until one day last winter, wrapped up in furs, I sat in the sleigh with the little fellow in my lap as usual. Billy Ring, one of my old hunting guides, walked by. He stopped, and taking his pipe out of his mouth nodded at the little dog and said, 'Have you come to that, Doctor?'" Photograph No. P82.33 courtesy of Adirondack Research Room, Saranac Lake Free Library. Adirondack Daily Enterprise, April 26, 2014 Dr. Edward Trudeau

Dr. Edward Trudeau  Trudeau's Cutter, a gift from E. H. Harriman. According to Trudeau's grandson, Harriman tried unsuccessfully to give money to Trudeau for his own use. Finally, he sent this sleigh along with a pony and groom, endowed for life, with a note reading "Try and give this to the Sanitarium." c. 1900. At the Adirondack Museum Born: October 5, 1848, in New York, New York

Trudeau's Cutter, a gift from E. H. Harriman. According to Trudeau's grandson, Harriman tried unsuccessfully to give money to Trudeau for his own use. Finally, he sent this sleigh along with a pony and groom, endowed for life, with a note reading "Try and give this to the Sanitarium." c. 1900. At the Adirondack Museum Born: October 5, 1848, in New York, New York

Died: November 15, 1915, in Saranac Lake, New York

Married: Charlotte Beare

Children: Charlotte Trudeau, who died of tuberculosis in her late teens; Edward Livingston Trudeau, Jr., who died in his twenties; Henry, who died in infancy; Francis Berger Trudeau

Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, MD, MS, D. Hon, was a doctor who established the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium at Saranac Lake for treatment of tuberculosis.

A brick at the Saranac Laboratory has been dedicated in the name of E. L. Trudeau, M.D. by Historic Saranac Lake. Trudeau was born in New York City to a family of physicians. During his late teens, his elder brother James contracted tuberculosis and Edward nursed him until his death three months later. At twenty, he enrolled in the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University (then Columbia College), completing his medical training in 1871. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1873. Following conventional thinking of the times, his physicians and friends urged a change of climate. He went to live in the Adirondacks, initially at Paul Smith's Hotel, spending as much time as possible in the open; he subsequently regained his health. In 1876 he moved to Saranac Lake and established a medical practice among the sportsmen, guides and lumber camps of the region.

A brick at the Saranac Laboratory has been dedicated in the name of E. L. Trudeau, M.D. by Historic Saranac Lake. Trudeau was born in New York City to a family of physicians. During his late teens, his elder brother James contracted tuberculosis and Edward nursed him until his death three months later. At twenty, he enrolled in the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University (then Columbia College), completing his medical training in 1871. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1873. Following conventional thinking of the times, his physicians and friends urged a change of climate. He went to live in the Adirondacks, initially at Paul Smith's Hotel, spending as much time as possible in the open; he subsequently regained his health. In 1876 he moved to Saranac Lake and established a medical practice among the sportsmen, guides and lumber camps of the region.

In 1882, Trudeau read about Prussian Dr. Hermann Brehmer's success treating tuberculosis with the "rest cure" in cold, clear mountain air. Following this example, Trudeau founded the Adirondack Cottage Sanitorium, with the support of several of the wealthy businessmen he had met at Paul Smiths. In 1894, after a fire destroyed his small laboratory, Trudeau organized the Saranac Laboratory for the Study of Tuberculosis, the first laboratory in the United States for the study of tuberculosis. Renamed the Trudeau Institute, the laboratory continues to study infectious diseases. One of Trudeau's early patients was author Robert Louis Stevenson and in gratitude, Stevenson presented Trudeau with a complete set of his works, each one dedicated with a different verse by Stevenson (the books were later lost in a fire). Trudeau's fame helped establish Saranac Lake as a center for the treatment of tuberculosis.

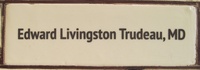

Dr. E. L. Trudeau at work in the Saranac Laboratory, c. 1895

Dr. E. L. Trudeau at work in the Saranac Laboratory, c. 1895

Courtesy of the Adirondack Experience

Trudeau had a camp on Upper Saint Regis Lake, and was active in the community, helping to found St. John's in the Wilderness Episcopal Church in Paul Smiths, where he is interred, as well as the Church of St. Luke, the Beloved Physician, in Saranac Lake in 1879, and the Village of Saranac Lake, of which he was the first president (mayor) in 1892. He was also a founder of the St. Regis Yacht Club.

Trudeau and his wife, Charlotte Beare, had one daughter, "Chatte," who died of tuberculosis in her late teens; and three sons, Edward Livingston Trudeau Jr., a physician who died in his twenties; Henry, who died in infancy; and Francis Berger Trudeau, a physician who succeeded his father at the sanatorium as director until 1954. Francis Berger Trudeau's son, Francis B. Trudeau, Jr. was the father of cartoonist Garry Trudeau.

On May 12, 2008, the United States Postal Service issued a 76 cent stamp picturing Trudeau, part of the Distinguished Americans series. An inscription identifies him as a "phthisiologist" (an obsolete term for a tuberculosis specialist). 1

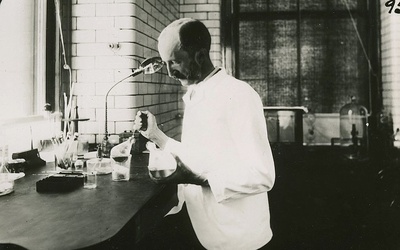

Edward Livingston Trudeau was a relation of Prime Ministers of Canada, Pierre and Justin Trudeau. Their common relative was Etienne Trudeau, born 1641 in France, died 1712 in Montreal. Statue of E. L.. Trudeau by Gutzon Borglum.

Statue of E. L.. Trudeau by Gutzon Borglum. Statue of E. L. Trudeau by Gutzon Borglum. Originally erected at the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium, it is now at Trudeau Institute.

Statue of E. L. Trudeau by Gutzon Borglum. Originally erected at the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium, it is now at Trudeau Institute.

Marie Shay and family with Trudeau statu

Marie Shay and family with Trudeau statu

Mrs. Trudeau, Dr. Trudeau, Dr. Luis Walton

Mrs. Trudeau, Dr. Trudeau, Dr. Luis Walton

New York Times, November 16, 1915

DR. E. L. TRUDEAU DEAD AT SARANAC

Pioneer of the Open-Air Treatment for Tuberculosis— 67 Years Old.

HIMSELF A CONSUMPTIVE

Went to the Adirondacks in 1873 When His Case Had Been Pronounced Hopeless.

Special to The New York Times

SARANAC LAKE, N. Y., Nov. 15. —Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, pioneer in America, of the open-air treatment for tuberculosis, and head of the famous Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium, died here today after over forty years' battle against the disease to the conquest of which he devoted his life. He was conscious almost to the moment of death. At his bedside were Mrs. Trudeau and a son, Dr. Francis B. Trudeau; also his cousin, Lawrence Aspinwall of New York, and his personal physicians. Dr. Edward R. Baldwin and Dr. J. Woods Price. The entire town and community which grew up around his labors of humanitarian science are tonight in the profoundest gloom.

The funeral will take place Thursday evening. The service is to be at the Church of St. Luke the Beloved Physician, which he founded here a quarter of a century ago. The interment will be in the churchyard of St. John's in the Wilderness, which he founded also, at Paul Smith's, and where a daughter and a son lie buried.

For the wave of agitation for open windows in offices and homes that has swept the country in recent years and for the erection throughout the United States and Canada of about 500 sanatoria for the open-air treatment of tuberculosis the example and influence of the late Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau are mainly responsible.

E. L. Trudeau, c. 1876

E. L. Trudeau, c. 1876

Photograph by George W. Baldwin

Courtesy of the Adirondack ExperienceHe was the pioneer in America of the practice of those theories laid down by Brehmer and Dettweiler, who insisted that climate is not the only and all-important factor in treating tuberculosis and that the consumptive is never injured by exposure to inclement weather provided he is accustomed, or accustoms himself, to living constantly out of doors. It was upon this theory that Dr. Trudeau built in 1880 a shack in the Adirondack wilderness, where he tried the "cure" himself and coaxed two other patients to sit in a chair in the open all day wrapped up in blankets when the thermometer was somewhere around 40 below zero. But the experiment was so successful that today, where that little shack still stands, around it have risen the many vast buildings that make up the little mountain town of Trudeau, N. Y., and less than two miles away has sprung up Saranac Lake, which grew with Trudeau's great work from a sawmill and six houses in 1877 to a sanitary city from which New York is said to have modeled its health code.

Repeated Koch's Experiments.

Dr. Trudeau was also one of the first scientific workers in this country to obtain the tubercle bacillus in pure cultures after Koch's announcement of its discovery in 1882. Trudeau also repeated all Koch s inoculation experiments despite the fact that he had no books, no apparatus, and, as he confessed himself, " an indifferent medical education." He had to keep his guinea pigs in a hole in the ground and warmed it with a kerosene lamp to prevent their freezing in the Adirondack Winter nights. He grew his tubercle bacilli in a home-made thermostat heated by a kerosene lamp, which exploded one night while he was in New York City and ill and burned his house, cultures, records, guinea pigs, and everything to the ground. The blow was a terrible one to the aspiring young physician, but he took heart from a letter which Sir William Osler sent him.

"Dear Trudeau," wrote Osler. " I am sorry to hear of your misfortune, but, take my word for it, there is nothing like a fire to make a man do the phoenix trick."

Trudeau did it. Almost upon the ashes of his crude laboratory presently arose the first and perhaps best-equipped laboratory for medical research in America. George C. Cooper of New York came forward with the necessary capital. It was out of this laboratory that (as Dr. Trudeau's death lifts the embargo of secrecy) there came the article which, published in the Sunday edition of THE NEW YORK TIMES on the very morning that Dr. F. P. Friedmann arrived in this country, caused many physicians to change their opinions overnight as to the merits of the German's claim of a "cure" for tuberculosis by his "turtle" serum. The article, while the writing was done by his assistants, was really an expression of the views of Trudeau, who had known, studied, and discarded as useless the germs that both Friedmann and Piorkowskl tried to commercialize.

Dr. Trudeau's Career.

Edward Livingston Trudeau was born in New York City in 1848. His father and mother were both of French descent, James Trudeau, a friend and fellow-traveler of Audubon, having come of an old Huguenot family which came from France to Canada, then drifted down the Mississippi in the early days to New Orleans, near which city he owned a plantation. The doctor's mother was the daughter of a New York physician of French birth, Dr. Eloi Francois Berger. James Trudeau died of wounds received while commanding Island No. 10 in the Mississippi during the civil war. Mrs. Trudeau then lived with her father in New York. When the youngest of her three children, Edward L. Trudeau, was only 3 years old the family went to Paris, where the boy was educated. He returned to New York City when he was 18 and hardly able to speak a word of the language of his native city. He planned to enter Annapolis after graduating from Columbia, but an elder brother who had preceded him to the Naval Academy was stricken with tuberculosis. Young Edward nursed him and contracted the disease, of which his brother shortly died. Thus he came in contact with the scourge to the extermination of which he determined to devote the rest of his life.

He entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons of New York City, was graduated in 1871, and in the same year entered into partnership practice with Dr. Fessenden Otis in New York. In the same year he married Miss Charlotte Beare of Douglaston. L. I., who has been his mainstay throughout many a period of discouragement, for their life together was marked by many a tragedy, the death of all their children save one, Dr. Francis B. Trudeau, who, with Mrs. Trudeau, survive. Dr. Edward L. Trudeau, Jr., died in 1906.

The first tragedy—which was fortunate for the world—was when Dr. Trudeau was pronounced a hopeless case of tuberculosis. He was 26 years old and the physicians gave him six months to live. He survived nearly half a century, kept up by his own grit and enthusiasm for the betterment of others and the defeat of the disease which ultimately killed him.

Went to Adirondacks In 1873.

On the advice of the famous Dr. Alfred L. Loomis he went to Paul Smith's in the Adirondacks in 1873, accompanied by his friend Lewis Livingston of New York. Paul Smith's was then a clearing house forty miles from nearest Railway station at Ausable Forks. When Trudeau was brought to Paul Smith's he was carried upstairs and put to bed by a guide who said he "weighed about as much as a sheepskin." At Smith's Trudeau improved thanks to the tender nursing of Livingston. Paul Smith and the late E. H. Harriman, who was then staying at the wilderness inn. Harriman became his life-long friend, pouring money into his lap for his altruistic work. It is a fact that when Harriman was a king in power, financial princes had to cool their heels in the anteroom of his office while the frail country doctor, visiting New York, was joyously received.

For the next three years he lived in the Adirondacks through Winter and Summer, proving that a man in the last stages of tuberculosis could not only survive, but benefit by the rigid wilderness Winter. He hunted like a born woodsman, was a dead shot, and—amazing truth!—was the quickest man with the gloves that ever entered a backwoods amateur ring.

Doctors the Woods People.

In the meantime he doctored the woods people within a radius of forty miles, attending Summer visitors at Saranac Inn and Paul Smith's and the settlers in Winter. He was also called in for sick cows, horses, and dogs. He would travel thirty miles in the blizzard to usher a little woodsman into the world, and frequently forgot to send his bill. He was known as "The Beloved Physician."

In 1877 he moved to Saranac Lake, a hamlet with a saw mill and six houses. His patients came to him there and New York doctors began to send tubercular cases to him as a last hope. He dreamed about this time of a sanitarium "that should be the everlasting foe of tuberculosis," but it was years before the dream was fulfilled.

It was in 1885 that he built the "Little Red" shack on Mount Pisgah, near Saranac Lake. This was the nucleus, costing $350, of the great Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium which has wielded such a widespread influence. The present sanitarium is a million-dollar institution run on a semi-charitable basis and at a deficit of from $10,000 to $20,000 a year. Trudeau never accepted a penny for salary as director.

Stevenson His Patient.

During his forty years of labor in the battle against tuberculosis Dr. Trudeau had many distinguished patients, among them Robert Louis Stevenson, who lived at Saranac Lake in 1887-88 and there produced some of his greatest work. In a special set of his works presented to the doctor Stevenson wrote a couplet in every flyleaf. In the doctor's "Jekyll and Hyde," for instance, appears in Stevenson's writing:

Trudeau was all the Winter at my side, I never saw the nose of Mr. Hyde.

These two men—as yet unconscious of each other's greatness—had many amusing arguments, and sometimes they would not speak for weeks, after, for instance, a quarrel regarding the respective merits of the British luggage system and the American baggage system. Again, Stevenson had just finished his great essay, "The Lantern-Bearers," when he went to Trudeau's laboratory to hear something about his "light." The sight of the ravages of disease which Trudeau showed in bottled form was too much for Stevenson. He bolted out into the snow and later said:

"Trudeau, your light may be very bright, but to me it smells of oil like the devil."

Honored for His Labors.

Trudeau Memorial depicted on Scenic Photo-Tone Miniature

Trudeau Memorial depicted on Scenic Photo-Tone Miniature

Trudeau was highly honored for his labors during his lifetime. He received, among other degrees, the LL. D. of both McGill and the University of Pennsylvania, Master of Science of Columbia, and Honorary Fellow of the Phipps Institute. The Pennsylvania degree was conferred in absentia, Dr. Trudeau usually being too ill to leave Saranac Lake. Yale offered to confer an LL.D., but the doctor was unable to leave his bed to be present. In 1910 he was President of the Eighth Congress of Physicians and Surgeons at Washington. D. C. Hardly able to stand on his feet, he addressed his colleagues on "The Value of Optimism in Medicine." It was his last great public utterance. His voice hardy audible because he was suffering intensely as he spoke, he concluded thus: "So let us not quench the faith nor turn from the vision which we carry, whether we own it or not; and thus inspired, many will reach the goal."

New York Times, November 21, 1915

Trudeau's Life a Rare Romance in Medicine; A Hopeless Sufferer from Tuberculosis, He Found in the Adirondacks the Secret of Conquering the Disease and Became a Healer of Thousands

THE recent passing of Dr. Trudeau, pioneer of the anti-tuberculosis campaign in America, removes a unique and cherished figure from the ranks of those who help to help the world. He was enshrined as the "beloved physician" in more hearts than can ever be counted. His patients were of every kind and degree, and hailed from all over the world. He came into their lives almost always at the peak of those hopeless sorrows that try men's souls;

he always lightened the load, even when he could not lift it.

It was thus he came into my life. I had been stricken—out of a clear sky, as it then seemed to me—with tuberculosis. I was sent, in the end, to Saranac Lake, where I lay on my back in bed waiting for the doctor to call. It was a mid-Winter morning. The snow was four feet deep outside. The air was cold and clear. The sky was intensely blue— and so was I. Then the door opened, and the room became filled with a personality.

The person was tall and lean, clothed as for Winter sports—a seemingly close-fitting suit, no overcoat, a sweater worn high about the neck, and trousers tapering into long, lumberman's socks, known as "Pontiacs." Above this picturesque costume emerged a head that seemed abnormally large, for the broad, protruding brow was accentuated by baldness. The eyes were deep set; the cheekbones prominent. Beneath an aquiline nose was a small, sensitive mouth, and finely chiseled chin, surrounded by a mustache and sidewhiskers. Such was the outward man: and the first impression was inevitably of bodily length capped by mental breadth.

His movements were rapid and lithe, but never jerky. He was obviously a nervous, restless, high-strung man, and yet he brought into the sick room some magic that soothed, nothing that jarred. His voice had much to do with this. It was unexpectedly smooth and low. His utterance was copious and rapid, yet distinct and modulated. I remember thinking of colored silk unwinding from a spool.

He began speaking as soon as he had crossed the threshold. He offered me no phrases of sympathy, and yet he radiated nothing else. He brought to my bedside not only the presence of a genial doctor, but the kinship of a fellow-sufferer. This was the bond that brought him so close to all his patients. He was not merely an outsider fighting for them; he was an insider fighting with them, as the story of his life will clearly show.

Edward Livingston Trudeau was born in New York City on Oct. 5, 1848. His family was, as the name suggests, of French descent, and his father, Dr. James Trudeau, came from New Orleans. The son was sent abroad at an early age and educated at the Lycee Bonaparte in Paris. This gave him a command of French which stood him in good stead for the scientific investigations of his later life. I doubt, moreover, if any but a few intimate associates knew of this resource and that he spoke the language with an accent which a foreigner can only acquire in youth—and in Paris. To hear him say: "Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité " was to hear a Frenchman speak.

He returned to New York in 1867 and knocked around a bit from one thing to another. Then he secured an appointment as midshipman to the Naval Academy. He had scarcely accepted this opening, however, when fate, with one of those interpositions which seem almost intelligent, changed his career. His brother was stricken with consumption, and Edward returned to New York to take care of the sick man. This meant the ministrations of personal attendance —nothing more. Trained nursing, as we know it today, was still an undiscovered art, and the cause of the disease was as unknown as any method of combating it. Indeed, Dr. Trudeau used to tell that the superlative injunction of the attending physician was not to open a window, as fresh air would only aggravate the patient's cough.

The brother died at the end of a few months. The result of the experience was to cause young Trudeau to study medicine, but without the faintest idea of thereby helping to solve the terrible riddle of consumption. This came about by coincidences as unforeseen as those which had unexpectedly led him into the profession.

He was graduated from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1871, and started practicing as a partner of Dr. Fessenden Otis in New York. The same year he married Miss Charlotte Beare of Douglaston, L. I. Within twelve months, however, he developed tuberculosis as a result of hard work and a run-down condition. Nor was this surprising in view of his admission that during his brother's illness he had been not only constantly confined in the unaired room, but had frequently, for some seeming advantage, slept in the same bed with him.

Dr. Janeway told Trudeau he must give up practice, and advised him to go South. The advice was followed, but no improvement resulted. In May, 1873, Dr. Trudeau returned to New York much sicker than he had left it. He was again ordered out of the city. This time he himself made the choice of destination, and it was purely a haphazard one. On vacations he had hunted and fished in the Adirondacks, and he now decided to return to Paul Smith's, a place that he knew and liked, and which had always agreed with him. He induced a friend, Lewis Livingston, to accompany him, and the two young men set out together. Dr. Trudeau was so weak that he had to be carried wherever there was any walking to be done. At Plattsburg he was obliged to rest for several days, and it seemed highly improbable that he would ever reach Paul Smith's alive. He was not to be dissuaded from continuing the journey, however. A spur of the railroad went to Ausable Forks, but from that point all transportation was by stage. A mattress was placed on one of these, and on it the invalid rode all day, over rough corduroy roads, to his destination, forty-two miles away. He reached it in complete exhaustion. He was carried upstairs to his room by his old friend and guide, Charlie Martin, who genially compared the doctor's weight to a lambskin's.

Paul Smith's in those days, of course, was a very primitive abode—a mere hunting lodge for sportsmen in the heart of the wilderness. It was considered both ill-fitted and inaccessible for women and children. At least so thought the good doctor when be first chose exile there without wife or family. His friends did all they could, however, to supply the deficiency. There were two of the Livingstons, and each of the brothers spent a month with the doctor. Paul Smith was always fond of telling how each at leaving had come to him and said: "Well, I've said good-bye to the doctor for the last time. I'll never see him again."

This proved to be true—but the reason was because both of these big, strapping brothers died soon after. Another friend who took a turn at watchful waiting with the invalid was E. H. Harriman, whom the dying doctor also finally outlived. This was an early boyhood friendship that lasted through the widely divergent careers of the essentially different men. Not only did the man who grew to be very rich give delicately and helpfully to the friend who deliberately avoided money-getting, but the great financier held the gentle doctor in an esteem and affection above other men. If he went to the mansion in New York, where many a mighty railroad conference was held, and chanced upon some calling magnate, it was more apt to be the latter than the country doctor who waited for an audience. The butler had orders never to turn him away.

During his stay of three months at Paul Smith's Dr. Trudeau gained appreciably, and the idea of spending a winter in the Adirondacks crossed his mind. He realized that the North Woods had somehow done him a good turn, and he was reluctant to leave them. He unfortunately yielded to the suggestion, however, of spending the Winter in St. Paul, Minn. The climate was cold there, and was therefore thought to be beneficial. It did not prove so in the doctor's case, however. He lost in health all that he had previously gained. But he learned his lesson—that the Adirondacks were the only place for him.

In the Spring of 1874, he returned to them. He thought at the time they might yield him a few months' reprieve; as a matter of fact, they gave him over forty years of unparalleled usefulness. This time, however, he took his wife and two children—a little son and a daughter —with him. He began to pick up again at once, and when Fall came, he had made up his mind to spend the Winter right where he was. This was a rather momentous and astounding decision, considering all the circumstances, and it was met with no enthusiasm by the Smiths. They were willing to do anything within reason to oblige the doctor, but his request to be kept through the Winter seemed a little unreasonable. No city person had ever suggested such a thing before, and this emaciated consumptive seemed the last one who could face the rigors of an Adirondack Winter and withstand the inevitable discomforts and isolation that it brought to such a place, forty-two miles from the nearest railroad. But the doctor insisted and pleaded, and, as usual, won the day. The Smiths had grave doubts about having done him any real kindness, however, and fully expected he would die on their hands, beyond the reach of the alleviations they would wish for him. However, instead of dying, he surprised everybody by improving rapidly and substantially.

When the Fall of 1876 came the doctor again wished to hibernate with the Smiths, but, perhaps because he would not move out, they decided to take the initiative. At all events the ever active Paul had bought the Fouquet House in Plattsburg, and had made his plans to run it during the coming Winter. This forced the doctor to go elsewhere, and, having little choice of location in the then sparsely settled Adirondacks, he decided on the then "miserable hamlet" of Saranac Lake. He moved to it in the Fall of 1876.

During his first Winter in Saranac Lake he fell in with Fitz-Greene Halleck, one of the best hunters in the country. They would hunt rabbits and foxes together in the snow, and a friendship was thus formed that lasted through a lifetime. Halleck claimed that for quickness and accuracy in hitting anything that moved the doctor had no peer. His favorite illustration "of this was the following story: They were out hunting rabbits one day near a swamp. The dog had started one and was gunning it toward the doctor. As it came nearer, a frightened partridge flew up. The doctor, who had a shotgun, brought down the bird with one barrel, and then killed the rabbit with the other—a truly remarkable feat of dexterity.

But shooting was not the doctor's only sporting accomplishment, although in the nature of things it was the only one in which he could indulge to any extent after his health broke down. He was also very fond of boxing, and could handle the gloves no less expertly than the gun.

Expecting to die soon, he had gone to the mountains to await the inevitable, but, while waiting, he was getting better —much better. Could it be that the climate and the outdoor life had something to do with the paradox? The answer seems so obvious today that it is difficult to realize that it was not so then. But forty years ago tuberculosis was considered an incurable and unpreventable, because inherited, disease. Its cause was unknown, and science had not even devised palliatives for its relief. Its victims were simply doomed to die—the sooner the better in most cases. These were the conditions against which Dr. Trudeau began to weigh his experience and pit some conclusions. He began to perceive that the mere being out of doors was benefiting him, and that exercise was often detrimental, especially if he had any active symptoms of his trouble.

About this time he chanced upon the theories of the German physician, Brehmer, who tentatively advocated the outdoor and institutional treatment of tuberculosis. This paper impressed the younger man profoundly, and he felt instinctively that the German was on the right track. Then, in 1882, a memorable year in medical science, Koch gave to the world his epoch making discovery of the tubercle bacillus. Through a friend Dr. Trudeau secured an early translation of the " Etiology of Tuberculosis," and the reading of this remarkable paper fanned into flame the smoldering embers of desire—into flame that no difficulties could dim; that no discouragements could squelch—into flame that burned ever brighter as a beacon light on the slowly charted coast of a dread disease.

From this moment the doctor's life suffered a radical change. The quest of his own health became secondary to the saving of others. The hunting of rabbits, foxes, and deer became the luxury of rare relaxations, whereas the hunting of the elusive tubercle bacilli became the vocation of a busy life. Up to this time of his exile he had not taken a medical journal or more than glanced into a medical book. He now improvised a crude laboratory in a little room in his house and set to work to repeat all of Koch's experiments. He had at first no suitable apparatus, no books, and even no training in the science of bacteriology. All these came by degrees, by patient effort and patient waiting.

There was no coal and no electric light in Saranac Lake in those days. The first laboratory was lighted by a kerosene lamp and heated by a wood stove, and on very cold nights the doctor often had to get up and replenish the fuel. In spite of such difficulties he succeeded in growing the tubercle bacilli in a homemade thermostat heated by a kerosene lamp, and was the second experimenter in the country to achieve this. After repeating Koch's experiments the doctor soon began making original ones. In the same week that Koch's announcement of the discovery of tuberculin was flashed across the ocean Dr. Trudeau published in The Medical Record the result of his attempts to produce artificial immunity in animals by injecting tuberculin.

In 1893, while he was away in New York, the lamp connected with the thermostat exploded and his home and laboratory were burned to the ground. Two days later Dr. Osier wrote him as follows:

"Sorry to hear of your misfortune, but take my word for it, there is nothing like a fire to make a man do the Phoenix trick."

The prophecy was rapidly fulfilled. The next day George C. Cooper, a patient and friend, called on the doctor and offered to build for him a real laboratory that would not burn. The outcome was the present stone and tile building, erected at Saranac Lake in 1894, in the rear of the new house which the doctor put up on the site of the old one. At first he had yearly to solicit funds to carry on the ever increasing activities of the new laboratory, but many years ago Mrs. A. A. Anderson, the well-known giver to philanthropic causes, relieved him of this burden by pledging annual support on condition that the laboratory be open to any doctor wishing to avail himself of its unusual advantages for the study of tuberculosis. This privilege has not only been accorded but freely encouraged. Later a splendid library was presented to the institution by Horatio W. Garrett of Baltimore. The index now shows 25,000 titles on tuberculosis and related subjects, and the number is rapidly increasing.

This was the first laboratory in this country devoted to original research in tuberculosis, and from it the doctor began to turn out work that was soon attracting attention all over the world. The experiments made and the papers written at Saranac Lake became the last word on tuberculosis. Gradually the doctor gathered around him a growing group of younger men, imbued with his ideals and trained to his high standards of research and experimentation. Under his guidance or inspiration they have done yeoman service in the great battle and achieved results that no man could have compassed single-handed. Foremost among them should be mentioned Dr. E. R. Baldwin, who lately received the honorary degree of Master of Arts from his Alma Mater, Yale, in recognition of his being "Dr. Trudeau's right hand man and an American authority on tuberculosis."

The lines of investigation pursued at the laboratory may be briefly summarized as follows: Testing specific methods of treatment and so-called consumption cures, proving the fallacy of methods aiming at the destruction of the tubercle bacillus in the living tissues by germicidal agents, animal experimentation seeking the production of immunity by injections of sterilized cultures and toxins, the chemistry of the tubercle bacillus and the possibilities of artificial immunity. But the work of the laboratory was always considered as merely subsidiary to the doctor's larger and more conspicuous enterprise—the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium. From the time of reading Brehmer's paper and noting its coincidence with his own experience he became more and more convinced that tuberculosis was a preventable and curable disease. Out of this conviction grew the desire for wider and more accurate knowledge, and then the dream of building an institution where the tuberculous of limited means could enjoy advantages otherwise beyond their reach. He began to talk earnestly and enthusiastically of this dream to various people, and to deplore his lack of funds for its inception.

He spoke of the matter one day to Anson Phelps Stokes, when the two were boating together on St. Regis Lake. Mr. Stokes told the doctor that if he ever decided to launch such an undertaking he was ready to give $500 toward it. This started the ball rolling, and soon the doctor had collected at Paul Smith's a fund of $5,000. Following this the guides and residents of Saranac Lake donated money enough to buy five acres of land on a sheltered hillside near the village.

It was here, in 1884, that the doctor erected two small buildings, and thereby laid the foundations of an institution which has become the model for all similar ones the country over. It represented the first application in America of the outdoor sanitarium treatment for tuberculosis according to the theories of Brehmer and Dettweiler, and in this connection it is of interest to note that, although Brehmer began to work out his principles of a regulated fresh air cure in 1859, and Koch did not discover the tubercle bacillus till 1882, the revelation of the specific cause of the disease did not alter or even modify the method of treatment.

Around Dr. Trudeau's first shack, which housed two rather shame-faced patients, a village has gradually grown. Besides the many detached cottages there is a large administration building, another laundry and service building, an infirmary, a recreation pavilion, a work shop, a drug store, a library, a church, and a Post Office. The latter was established in 1904 under the official and commemorative designation of "Trudeau, N. Y."

The basic idea of the Sanitarium was to furnish the best treatment and medical advice to poor patients at less than it cost to run the institution. The burden of supplying a yearly deficit through voluntary contributions was faced from the outset, and it remained the dominant responsibility and anxiety which Dr. Trudeau always personally shouldered. It was a burden, moreover, that always kept pace with the growth of the institution. While many have given steadily and liberally, no one has ever offered the larger amount which would supply the total income needed. No word of complaint on this score, so far as I know, ever crossed the doctor's lips, but there is little doubt that it was a consummation he devoutly wished and which would have gilded more than anything else could have done the sunset of his life.

In 1910 the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary by fitting and impressive ceremonies. The event brought to Dr. Trudeau words of congratulation and tokens of esteem from eminent men all over the world.

Aside from his lofty idealism and indomitable optimism, two other spiritual sources have fed the doctor's life: a deep religious sentiment and a deep love for his wife. From his faith in God he drew his faith in man and himself. His religion, moreover, had the rare distinction of never being preached but of always being practiced. His reaction to the teachings of Christ was as sensitively humanitarian as his reaction to the merely mortal teachings of Brehmer and Koch—he applied both. Dr. Trudeau and his wife were the founders, and have ever since been the mainstay, of the Episcopal churches at Paul Smith's and Saranac Lake. He nursed them along through troublesome times, like many another of his disheartened patients.

His love for his wife, and hers for him, became the basis of perfect mating —active comradeship and quiescent understanding. Wherever the doctor had to go, Mrs. Trudeau always went if possible. The routine of his life was to spend the Winters in Saranac Lake, the Summers at Paul Smith's, sixteen miles away. In Winter he drove daily to the Sanitarium, one mile out of the village; in Summer he drove over from Paul Smith's regularly once a week. On these drives Mrs. Trudeau, unless indisposed, was always at his side, and her absence was always a cause for comment. These two being drawn to their daily task by "Kitty," their ambling, unhurried, shaggy, plush-like little horse, was a sight that seemed as much a part of the village life as the striking of the Town Hall clock.

On all the notable celebrations in his career the doctor gracefully placed the laurels of his success at the feet of his loyal wife, to whom he attributed the credit for all he achieved.

The doctor's public life has of late years known the rewards of straggle and the greenest laurels of unselfish endeavor. He has not only been widely and supremely honored, but with the honors has been made manifest a universal feeling of affectionate regard which is not always a part of the ritual of renown. The first formal outside recognition of his labors came in 1899, when the honorary degree of Master of Science was offered him by Columbia University, and he was elected one of its trustees. In 1904 McGill University conferred upon him the degree of LL. D. In 1905 he was elected the first President of the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. The same year he was also chosen President of the Association of American Physicians, and Yale offered an LL. D., but he was too ill to attend the ceremony. In 1908 he was made Honorary President for America of the International Tuberculosis Congress. In 1910 he was tendered the presidency of the Congress of American Physicians and Surgeons, which he held to be the highest honor within the gift of the medical profession. In May, 1913, he received the degree of L.L. D. from the University of Pennsylvania. Custom requires the presence of those about to receive a degree, but in this case, owing to the doctor's illness at the time, precedent was waived and the degree conferred "in absentia," an added honor.

With the relapses of his disease and the waning of his strength, the doctor gradually gave up the practice of medicine and turned it over to the younger men who had clustered around him. He devoted his time and attention solely to the Sanitarium and the laboratory, and allowed himself a little more rest and play.

This was only made possible, it should be noted, by the thoughtful, unfailing generosity of his friends. He never accumulated money by the practice of his profession. He made enough to support his family and educate his children— and that was all. From the poor he took nothing; but to them he often gave of his slender means. His fee for those who could afford to pay was always indiscriminately modest. It was never a graduated income tax. I always remember my first bill from Dr. Trudeau as one of the greatest surprises of my life. I came to see a specialist of world-wide fame, and the fee was that of an obscure country doctor! He inaugurated the high land values and general prosperity of Saranac Lake, but he scrupulously avoided making money out of the opportunities he had created.

Dr. Trudeau probably had a greater number of diversified patients—from the very poor to the very rich—than any other physician in private practice; he probably had also more hopeless cases. But if these and the living could be brought together, there is little doubt that they would unite in praising the lovable and sympathetic quality of his physicianship as something unforgettable. Where he could give no medicine —and perhaps no doctor ever gave less— he generally managed to convey comfort or cheer in some form, and to leave his patients mentally better than he found them. This is the essence of the higher physicianship—the doctoring of the soul. The man who is sick in body is also sick in mind. Those who ignore this are little better than itinerant apothecaries and are largely responsible for the excesses of Christian Science; those who find the happy mean are destined to be remembered as great practitioners, like Dr. Trudeau.

His notable address on optimism before the Congress of Physicians and Surgeons in 1910 was written under circumstances which lend it peculiar interest as well as value. It was my privilege to be calling on the doctor shortly after it had been delivered, and our talk veered around to it. Laughingly, with no thought of anything bat the grim humor involved, he told me the story of its composition. He had been suffering from one of his most-serious relapses—high fever, acute coughing spells, and broken sleep. He woke in the small hours of each morning, and lay tossing uncomfortably on his bed. Then it occurred to him that instead of lying there idly between coughs, thinking of himself and his troubles, he might better concentrate his mind on some preparation for the great meeting over which he had been asked to preside. So he turned on the light near his bed, reached for pad and pencil, and began the rough draft of this notable address on optimism. Not long after he was able to leave his bed and deliver it in person. What it means to turn out optimistic literature under such conditions only those who have tasted them can realize; but the unusual feat is essentially typical of Dr. Trudeau's whole career.

His sensitive ear caught the first rumblings and his optimism crystallized the random nativities of a great movement; and in his frail but virile person there lurked the idealist who was destined to become its leader. New wars develop new and unexpected Generals. The tuberculosis war developed Trudeau, Coeur de Lion.

New York Tribune, July 3, 1910

Dr. and Mrs. Edward L. Trudeau came yesterday and opened their cottage at Paul Smith's for the season. Dr. A. Schuyler Clarke, of New York, is staying at the Trudeau Cottage. Francis Trudeau is also here, and has brought his new automobile with him. Mr. Trudeau has placed his fast boat, the P. D. Q., in commission for the season's events.

Trudeau's gravesite, St. Johns in the Wilderness Church

Trudeau's gravesite, St. Johns in the Wilderness Church

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, November 15, 1926

TRIBUTE TO DR. E. L TRUDEAU

Eleventh Annual Service to Be Held tomorrow Afternoon at Baker Chapel; Special Music Arranged

A memorial service in commemoration of the death of Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, founder of the Trudeau Sanatorium, will be held at the Baker Memorial Chapel, Trudeau, on Tuesday afternoon, November 16th, at 4:30 o'clock, The speaker will be the Rev. Robert A. Ashworth, pastor of the Baptist church of the Redeemer, Yonkers, N. Y.

The Rev. Mr. Ashworth thirty years ago was a patient in the Sanatorium and later in the village of Saranac Lake. He knew the late Dr. Trudeau personally and intimately, and since leaving here he has always had the interest of this Sanatorium at heart. He has used his influence, as opportunity presented, with excellent effect to help the institution.

Dr. Trudeau's favorite hymns will be sung as a part of the service. They are "Lead Kindly Light", "Work for the Night is Coming", and "Peace Perfect Peace". William A. P. Hennigar, organist, is arranging the music for the service."

The death of Dr. Trudeau occurred on November 15th, 1916, and this is the eleventh annual service to be observed in his memory. All those who knew him and all who are friends of the Sanatorium which he built, will be welcome to the service.

New York Times, March 13, 1947

TRUDEAU ASKS FOR AID

Sanatorium at Saranac Lake Opens Drive for $293,795

A campaign for $293,795 to help the Trudeau Sanatorium at Saranac Lake play its part "in a new era of hope for the conquest of tuberculosis" was announced last night at a meeting of the sanatorium's trustees in the Junior League Club, 221 East Seventy-first Street.

Rising costs and reconstruction needs, it was explained, require the raising of the money in 1947.

Five new trustees elected were F. Wilder Bellamy, W. Palen Conway, Albert H. Gordon, Dr. Anthony J. Lanza and George LaPan.

Sponsors of the campaign include John S. Burke, Henry A. Colgate, former Gov. Herbert H. Lehman, Peter Frelinghuysen, Robert Garrett, Newbold Morris, Cleveland Dodge, Samuel Lewisohn, Paul Moore, Gayer Dominick, Albert Milbank, Samuel Thorne and Allen Wardwell.

See also

- Edward Livingston Trudeau house and office

- A History of Saranac Lake

- Cure Cottages of Saranac Lake

- Doctor Trudeau

- Rabbit Island

- See the 1966 article by Helen Tyler on the Ormon Doty page about the guide boat that Trudeau took his first ride in after he came to Paul Smiths expecting to die.

- Sanitaria for the Treatment of Incipient Tuberculosis, a paper by E.L. Trudeau

External links

- Historic Saranac Lake - the Saranac Laboratory

- A contemporary description of the sanatarium

- New York Times, December 5, 1948, by Dr. Howard A. Rusk, "Sanatorium Is Monument to Pioneer Medical Fighter--Saranac Lake Result of Lifetime War by Dr. Trudeau on Tuberculosis."

- New York Times, July 23, 1905, "DOINGS IN THE ADIRONDACKS; Prominent Women Devoting Much of their time to Charity Work"

- Town of Brighton - St. John's in the Wilderness

- Trudeau postage stamp

Footnotes

1. This article was based on the Wikipedia article Edward Livingston Trudeau; its edit history there reflects its early authorship, which was licensed under the GDFL.