. Herb Clark (undated) Adirondack Daily Enterprise, October 26, 2012

Herb Clark (undated) Adirondack Daily Enterprise, October 26, 2012  The Clark family: from left, George, Mary, Herb Jr., Herb Sr. and Laddie. Courtesy of Cathy Mose.

The Clark family: from left, George, Mary, Herb Jr., Herb Sr. and Laddie. Courtesy of Cathy Mose.  Herb Clark (undated). Courtesy of Cathy Mose.

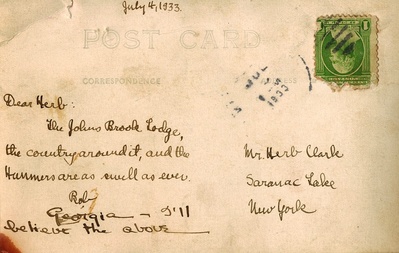

Herb Clark (undated). Courtesy of Cathy Mose.  A 1933 postcard from Bob Marshall to Herb Clark. Courtesy of Libby Clark.

A 1933 postcard from Bob Marshall to Herb Clark. Courtesy of Libby Clark.  Back of the postcard from Bob Marshall to Herb Clark. Courtesy of Libby Clark.

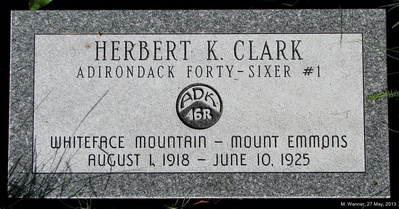

Back of the postcard from Bob Marshall to Herb Clark. Courtesy of Libby Clark.  A memorial tablet in St. Bernard's Cemetery recognizing Herb Clark as the first Adirondack forty-sixer. Born: July 10, 1870

A memorial tablet in St. Bernard's Cemetery recognizing Herb Clark as the first Adirondack forty-sixer. Born: July 10, 1870

Died: March 3, 1945 at the Saranac Lake General Hospital. He is buried at St. Bernard's Cemetery in the Clark family plot.

Married: Mary Dowdell in 1903

Children: Irene Clark Dimick, Gertrude Clark Montville, Herbert J. Clark, George Clark, James Clark, and Francis Clark.

Herbert K. Clark was a guide employed by the Louis Marshall family at Knollwood starting in the spring of 1906.

He was born near Keeseville, New York, and came to Saranac Lake in his early twenties. With Bob and George Marshall, he climbed what they then believed to be the 46 Adirondack Mountains higher than 4000 feet; climbing those 46 peaks still defines an Adirondack Forty-Sixer. Herb Clark is honored as 46er #1. On May 25, 2013 Herb Clark was honored with a ceremony inducting him into the Village of Saranac Lake Walk of Fame. On October 5, 2013 the ADK 46er organization at their annual fall meeting in Keene Valley recognized the achievements and contributions of Herb and bestowed upon him their Founders Award.

From Charles Brumley, Guides of the Adirondacks:

"In 1896 he began work at the club on Bartlett's Carry, between Upper and Middle Saranac Lakes. He worked as a night watchman for two years, then for five summers rowed the freight boat to Ampersand Bay and back daily, once carrying a load of 2,200 pounds, and another time rowed 65 miles in one day, 24 of those miles in the freight boat. For three years he worked only as a guide.

"In 1906, Clark began to work for the Marshall family on Lower Saranac Lake. Possessed of a fine sense of humor," he made up the grandest fables for the Marshall boys. . . .

"Clark coined the name 'cripplebrush' for the mountain balsam which can be so confining and frustrating on a mountain bushwhack. For years Clarks' catch of an 18 1/2 pound pickerel was a local record over a six-year period. Beginning in 1918, Clark climbed the 46 Adirondack peaks over 4,000 feet with George and Bob Marshall. In 1921 only 12 of those peaks had trails to their summits. Bob Marshall wrote: 'At the age of 51 he (Clark) was the fastest man I have ever known in the pathless woods. Furthermore, he could take one glance at a mountain from some distant point, then not be able to see anything 200 feet from where he was walking for several hours, and emerge on the summit by what would almost always be the fastest and easiest route."

From an article Bob Marshall wrote for High Spots in 1933 (in Phil Brown's Bob Marshall in the Adirondacks, Lost Pond Press, Saranac Lake, 2006).

Herb was born just before the great depression of 1873. His father, who had served three years with the army of the Potomac, commenced to get an $8.00-a-month pension in 1880, but from 1873 until 1880 the family was very much pinched for finances. There were eleven children, nine of whom survived infancy, and their support put a terrific strain on the diminutive income which the family got from the sale of its produce and from the odd jobs which the father and the older boys could pick up. Once the whole family went two or three days without anything to eat until someone gave them some potatoes. They had salt in the house, and that with the potatoes tasted to Herb the best of any meal he has ever eaten.

In spite of the austerity which this background may suggest, Herb from his childhood was a jocular and dashing young blade. His fondness for poking the keenest sort of satire at hypocrisy and sham, for twisting up blusterers in their own boastful stories, was something which friends who knew Herb in his youth tell me he possessed while he was in the early teens. He apparently was a very handsome young man in those days and a great favorite with the girls, whom he rushed by the wholesale.

In spite of his lightheartedness and his fondness for gay times, Herb was also a terribly hard worker, and he had a tremendous sense of loyalty to his family. He contributed materially to its income from the time he was twelve. For about five years he worked on the farm and in such odd jobs as he could pick up around Clintonville. In those days they paid fifty cents for a twelve-hour day at loading pulpwood. "They gave you a drink of water and that was all in the line of food."

Herb's first job away from home came in the summer of 1887 when he went up to Hank Allen's farm at North Elba to cut hay. After his father died in 1889 Herb went away to work every summer but returned to his mother in the winters. Most of his jobs required twelve hours' work in the day, but he was always fresh enough to spend a good half of the night in jollity. His wanderings took him to Miller's old hotel on Lower Saranac, to Vermont, to New Hampshire and to Saranac Village. In 1896 he commenced ten years of work at the old Club House at Bartlett's Carry between Upper Saranac and Round Lake. After his first winter there his mother died, and thereafter he made his home around the Saranacs.

He acted as night watchman at Bartlett's for two years, then for five summers rowed the freight boat twenty-four miles [round trip] between Bartlett's and Ampersand in the morning and guided in the afternoon and finally for three years devoted himself exclusively to guiding. The freight boat was a huge Adirondack guideboat, nearly twice the length of the normal crafts of that design, and Herb sometimes rowed as high as 2,200 pounds in one load. While at Bartlett's he made the record of having rowed about sixty-five miles in one day, twenty-four of them with this freight boat.

Perhaps it was such training which enabled Herb in those days to become undisputed champion among the rowers on the Saranac waters. In 1908 they held an all-Adirondack rowing race on Lower Saranac. This was won by a Blanchard of Long Lake, but Herb, although then thirty-eight years old, came in a close second, only a half a boat length behind in a field of eight or ten of the best rowers in the entire Adirondacks. The next year, with Blanchard out, everybody expected Herb to be champion, but the race was canceled. Herb continued as leading oars-man of the Saranacs through 1919, after which he retired from competition, as he always said he would do when he became fifty.

In the spring of 1906 Ed Cagle, who had guided for our family at Lower Saranac for six years, decided to open a livery stable, and by an almost impossible combination of circumstances it just chanced that Herb came to work for my father. At this time my brothers, sister and I were all under ten years of age. I cannot speak authoritatively of what Herb meant to the others, although I have strong suspicions. I do know positively that to me Herb has been not only the greatest teacher that I have ever had but also the most kindly and considerate friend a person could even dream about, a constantly refreshing and stimulating companion with whom to discuss both passing events and the more permanent philosophical relationships and, to top it all, the happy possessor of the keenest [sense] of humor I have known.

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, November 21, 1987

Herb Clark sensed right route to top

Maybe it's time to name a high peak after him

Herb Clark lived at 7 State Street where he kept the best garden in town. Early in the morning on any given summer's day Herb would be seen walking down the hill to the old Algonquin boat house where he kept his guideboat. Rowing a mile and a half, directly across Lower Saranac Lake, he would report for work at the Louis Marshall cottage in the Knollwood Club complex. Before the day was out Herb might well find himself atop one of the major Adirondack peaks with two of Mr. Marshall's sons.

Herbert K. Clark was born near Augur Pond, south of Keeseville, on July 10, 1870, one of eleven children. He spent his early years working on his father's farm and later, as a youth, he loaded pulp at nearby Clintonville, where he earned fifty cents for a twelve-hour day. During the summer 1887, at age 17, Herb worked at the Allen farm in North Elba in the shadow of the High Peaks.

Apparently this was the sort of country that appealed very strongly to him and he began to roam through the Saranacs. He worked at the ["Martin's"Martin] and Miller hotels for a while then moved to the Saranac Club at Bartlett's Carry, where he served as night watchman for two years.

Herb next took command of an oversized guideboat which was capable of carrying over a ton of supplies and passengers. He rowed the freight boat daily during the summer between Bartlett's and Ampersand Bay on the eastern end of Lower Saranac for a round trip distance of some 24 miles. This sort of exercise made Herb into a prodigious oarsman and he soon became the champion guideboat rower during the races frequently held on the Lower Lake. While at the Saranac Club Herb married Mary Dowdell, a co-worker at that establishment. Always an avid hunter and fisherman, he turned to guiding during his final years at Bartlett's. His expertise in this calling set the stage for more important things to come.

In 1906, Ed Cagle, who had served as guide for the Marshall family, decided to open a livery stable in Saranac Lake. Learning of the vacancy, Herb called on Louis Marshall and applied for the job. He was immediately hired in what proved to be the turning point in his career as well as the formation of a long-lasting association mutually advantageous to both the Clarks and the Marshalls. Never did Herb dream that two little tykes who, at that time were still not into their teens would later transform the champion rower of the Saranacs into a champion climber of mountains and very first of the Forty Sixers! The two boys were Robert and George Marshall.

With the prospect of steady employment at Knollwood, Herb and Mary made their home on State Street where they raised a fine family consisting of two girls and four boys. In addition to tending his prize garden, Herb frequently ventured into the Fish Creek marsh where he captured small frogs to be sold to the bass fishermen at the rate of sixty cents per dozen. He was an avid fisherman himself; from Augur Pond to the Saranacs he pursued the sport with great enthusiasm. He caught an eighteen-and-a-half-pound pike which for a time held the record on Lower Saranac. He once remarked to Bob Marshall, "I guess I was born fishing." Herb also loved to hunt deer with his fellow guides at Knollwood and later with his sons. Doubtless his early farm work, his rowing and his hunting conditioned a lanky frame into the shape which would serve him so admirably in his later calling, when endurance became such an important factor.

Although Herb had hunted the slopes of such local mountains as Shingle Bay, Boot Bay Mountain and Ampersand, he had never climbed a major peak. That lasted until 1918, when he led a party of Bob and George Marshall and Carl Poser to the summit of Whiteface. This initial climb was destined to develop into a campaign which was to end only after every Adirondack mountain 4,000 feet or higher had been conquered.

During the winter of 1920-21, at their home in New York City, Bob and George Marshall had selected 42 peaks for their assault agenda. Later this total was increased to 46 when it was learned that they had inadvertently overlooked Gray Peak, at 4,902 feet, and it was also decided to include Cliff, Couchsachraga, and Blake's Peak at an even 4,000 feet each.

Upon their return to Knollwood club on the following summer, the Marshall boys told Herb of their plan and the guide met the challenge with full enthusiasm. Little did the three realize that their ambitious scheme would later give birth to a cult which would be known as the "Forty Sixers" and which after 65 years, boasts, hundreds of disciples.

Today, aspiring Forty Sixers, those who seek to climb the 46 mountains, can drive their cars to Adirondack Loj at Heart Lake where a network of marked trails point the way to the High Peaks. Let's compare this modern approach to a typical day's work for Herb Clark.

Rowing his guideboat across the lake, Herb would pick up the Marshall boys at Knollwood and then row back across the lake to the Algonquin. Leaving his boat, the three would walk down to the railroad station and board the train for Lake Placid and, upon leaving the train, would then walk the eight miles to South Meadows before starting a climb. When finally reaching a mountain trail Herb became the leader, urging and teasing his charges ever upward. A daily climb might include one or two summits before the crew began their return to Knollwood Club over the same route as before. Quite a day's work! When the trio of climbers first began their specified assault on the 46 peaks, only twelve of the mountains had established trails, and these twelve had no trail markers. It was on the trailless peaks that Herb was able to display a rare ability in choosing the best route to each of the summits. He seemed to possess an intuition which enabled him to assess each situation with amazing accuracy when guidelines were nonexistent.

George Marshall paid tribute to this talent with explicit commentary. "Herb was really a marvel. At the age of fifty-one he was the fastest man I have ever known in the pathless woods. Furthermore, he could take one glance at a mountain from some distant point, then for several hours not be able to see anything 200 feet from where he was walking and emerge on the summit by what almost always would be the fastest and easiest route."

On many of the trailless peaks there was a thick growth of stunted spruce and balsam encircling the granite domes just above the timberline. This intertwined tangle presented a formidable deterrent to progress and caused many a scratch and bruise to the unwary climber. Herb aptly coined a term for this obstacle, which he called "cripple brush," and during an ascent of Mt. Colden he had reached a position high above his two companions. Suddenly, Bob and George heard their guide calling down to them in a booming rhyme:

"Don't let the golden moments go,

Like the sunbeams passing by, You'll never miss the cripple brush 'Til ten years after you die."

Such was Herb's sense of humor that was to surface sporadically throughout the years of mountain climbing with his two young and eager adherents. Many of their excursions were more than one-day affairs. On such trips during 1921 they trudged to 23 mountaintops, 18 of which had no trails and 7 that had never been climbed before. While tramping through cols and over summits Herb entertained his cohorts with outrageous tales of such famous characters of his imagination as Jacob Whistlecracker, Sliny Slott or Susie Soothing Syrup and who would dare to doubt the marvelous deeds accredited them by Herb's tongue-in-cheek accounts. The stream they passed would be where the Monitor and the Merrimac fought their famous battle and a peculiar dent in a huge boulder was where Captain Kidd bumped his head.

In recognition of Herb's climbing feats the Marshall brothers and Russell Carson, the author of "Peaks and People of the Adirondacks," felt that he deserved to have a mountain named in his honor. They chose a 4,411-foot summit in the Mclntyre Range, which they called "Herbert Peak". The name survived for some 30 years but was later changed to "Mount Marshall" in honor of the late Robert Marshall, who had attained national fame as a leading proponent of conservation. The reason given for the change was that since Herb was still living at the time, he could not have a mountain named for him according to the rules of the New York State Board of Geographic Names, which state that no natural object can be named for a living person. Now that Herbert Clark has passed on, perhaps the situation can be remedied.

John Adams Dix may have been a fine governor, but should he rate three peaks? Certainly there is no valid reason to change the name of Dix Mountain, a 4,857-foot peak in the southeastern fringe of the range. However, there could be a very good reason for changing the title of either 4,135-foot South Dix or 4,012-foot East Dix. Herb Clark is credited with a first ascent of both of these mountains so it would seem quite appropriate to name one of them in his honor, and no one would be hurt.

Once in a while a newspaper article can start the ball rolling on a proposal which can possible generate enough public interest to bring about a desirable and worthy change in precedent.

Although no such organization existed at the time, Herb and the two Marshalls were later named to be the first of the "Forty Sixers," a union formed in 1948 by a group of climbers from Troy. Herb was named number one, George Marshall number 2, and Bob Marshall number 3. Since that time the membership has grown to well over 2,300 adherents. Eligibility for membership in the club requires that an individual must, of course, scale all 46 peaks originally listed by the Marshalls. Perhaps some of the present membership might be willing to spearhead a drive to return Herb's name to a mountain, especially since it was due to the efforts of their organization that Herbert Peak was changed to Mount Marshall in 1940. I would respectfully submit a plan to re-name a mountain in honor of Saranac Lake's own Herber K. Clark. Since the mountain presently known as South Dix is separated from the main Dix by Hough Peak, it loses close proximity to its parent and becomes the logical nominee for renaming. For obvious and valid reasons, let's call it "Herb's Peak."

James Marshall, in a 1986 letter to the Adirondack Daily Enterprise, wrote: "Our guide, Herb Clark, was one of the finest people I ever knew, a fast and secure man in the woods, a splendid fisherman and hunter, and a tireless rower. We learned much from him and his company was always a joy."

The following is an excerpt from a letter that Ruth Marshall wrote to her future husband, Jacob Billikopf, in June 1918, when she was 20 (courtesy of her son, David Billikopf).

Just had a little conversation with my friend Herb, who was sweeping off the veranda. He was most sympathetic when I told him how early I got up and how it was all in vain. Then he tried to cheer me up (I’m really in awfully good humor at present) by telling me that he was going to catch a mess of white fish for our supper. I said to him, “Don’t work so hard Herb, you might get fat.” “Guess I was born to be a worker,” he replied. And so he was. Never saw a man as energetic - at least not among the guides, for most of them loaf all day - at any rate whenever they can. Herb is almost always busy at something. He’s got a nice little home which includes a wife, five children and a fine vegetable garden. His kids all had scarlet [fever] this winter, but he tells me they’re all fine again. He works in his garden frequently just as soon as it’s light and he makes quite a bit of money out of it. I buy some of my fresh vegetables from him and I tell you they’re dandy. He's the most comical looking man. Very tall and thin as a match. Sunburned and strong (he’s the best guide rower on the lake despite the fact that he claims to be 47. I say “claims” because I believe last year he said he was 48.) He’s a dandy fisherman and hunter and in fact a crackerjack of a guide in my opinion. Father thinks he’s somewhat of a “schlemiel” because he doesn’t always show intelligence, but still he appreciates most of his virtues. But Pop can’t enjoy Herb as we do, for Herb is on his good behaviour when in father’s company. He can keep me amused with his songs, stories and screamingly funny remarks for hours at a time. He’s hard of hearing and I usually have to yell at him to make him understand, but he usually gets most of my remarks and believe me our repartee is mighty funny at times. His face is somewhat of the American Indian type, though he’s far from good looking. Several people up here think he’s awfully homely, but I can’t agree with them. He teases the life out of the girls [probably Kate and Mary, two Irish-American sisters, who worked for the Marshalls as cook and maid] and I always tease him in return and say I’ll tell his wife on him. But he’s a mighty good man and most devoted to his family. His nephew Lloyd works up here also as guide for Mr. Cook, and when those two fellows get together telling stories, and swapping anecdotes - well, it’s worth coming ten miles to hear them. Lloyd is another one of my pals. A very good looking chap (about 29 but married), tall, well built, strong as an ox, a dandy athlete and sportsman & with a remarkable disposition. He’s a guide in the summer because it pays well and he loves the outdoor life. By profession he’s a dentist, but does not always stick to that work in the winter, for he has been a travelling salesman for several companies and worked at Greenhunt’s in New York one winter.

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, June 22, 2019

SLPD [police] blotter entries for June 1942

6/29/42, 8:45 P.M. Complaint from Herb Clark of No. 7 State St. Art Bowen's kids from Algonquin Ave. go into his berry patch and pick berries. Has warned them but they keep coming back. I warned Mrs. Bowen to keep the kids out. James & Wallace

Sources:

- Phil Brown, Bob Marshall in the Adirondacks (Saranac Lake: Lost Pond Press, 2006).

- Photos (from the Adirondack Collection, Saranac Lake Free Library and various other sources), published on pages xxvi (facing page 1), 39, 52, 53, 57, 88, 220 of Bob Marshall in the Adirondacks.

- Charles Brumley, Guides of the Adirondacks (Utica: North Country Books, 1994), 108-9.

Comments

2013-08-28 07:51:20 Where's his Walk of Fame plaque? —MaryHotaling

As of the fall of 2013 the Village of SL is still trying to raise the approximately $1,500 to pay for the plaque. - Jim Clark