Engine 1036 at Saranac Lake's Union Depot, 1930s

Engine 1036 at Saranac Lake's Union Depot, 1930s  Train wreck between Ray Brook and Saranac Lake. Photograph by Winchester MacDowell, undated. Courtesy of Marsha Morgan.

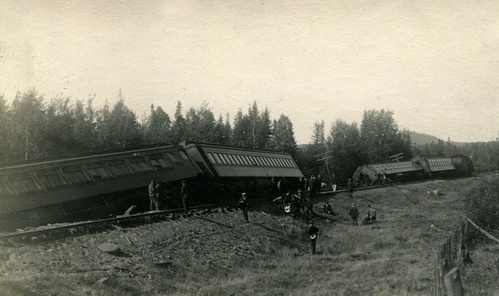

Train wreck between Ray Brook and Saranac Lake. Photograph by Winchester MacDowell, undated. Courtesy of Marsha Morgan.  Train wreck between Ray Brook and Saranac Lake. Photograph by Winchester MacDowell, undated. Courtesy of Marsha Morgan.

Train wreck between Ray Brook and Saranac Lake. Photograph by Winchester MacDowell, undated. Courtesy of Marsha Morgan.  Knights of Columbus members, May 24, 1914, with a special chartered train, stopped at Union Depot possibly in connection with an annual meeting, usually schedule in May. Adirondack Daily Enterprise, June 15, 2010 Railroad service to Saranac Lake first arrived on December 5, 1887, from the northeast, when the Chateaugay Railway Company extended its narrow-gauge service from Plattsburgh. On August 1, 1893, railroad service was extended the ten miles to the village of Lake Placid, where it terminated. The new track between Saranac Lake and Lake Placid was double-gauged to accommodate standard equipment as well as the narrow-gauge trains of the Chateaugay Railway Company. The standard equipment it was designed for was Dr. William Seward Webb's Adirondack and St. Lawrence Railroad (also known as the Mohawk and Malone), which approached Saranac Lake through Lake Clear Junction to the west (then called Saranac Junction) on its six-and-a-half mile Saranac Branch, beginning on July 16, 1892.

Knights of Columbus members, May 24, 1914, with a special chartered train, stopped at Union Depot possibly in connection with an annual meeting, usually schedule in May. Adirondack Daily Enterprise, June 15, 2010 Railroad service to Saranac Lake first arrived on December 5, 1887, from the northeast, when the Chateaugay Railway Company extended its narrow-gauge service from Plattsburgh. On August 1, 1893, railroad service was extended the ten miles to the village of Lake Placid, where it terminated. The new track between Saranac Lake and Lake Placid was double-gauged to accommodate standard equipment as well as the narrow-gauge trains of the Chateaugay Railway Company. The standard equipment it was designed for was Dr. William Seward Webb's Adirondack and St. Lawrence Railroad (also known as the Mohawk and Malone), which approached Saranac Lake through Lake Clear Junction to the west (then called Saranac Junction) on its six-and-a-half mile Saranac Branch, beginning on July 16, 1892.

After the whole Chateaugay line was converted to standard-gauge in 1902 and formally consolidated in 1903 into the Chateaugay and Lake Placid Railway Company, the present depots in Saranac Lake and Lake Placid were built. The railroads using these depots were the Delaware and Hudson (which had leased the Chateaugay's interest and built the new depots along their corporate standard lines, with local modifications), and the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad (formerly Webb's line) which now connected from Utica in the southwest. These depots were intended to serve the combined operations of both lines.

The following pages provide more detail on specific railroad topics:

- Adirondack Electric Road (never built)

- Adirondack Railroad Historic District

- Adirondack and St. Lawrence Railroad

- Chateaugay Railroad

- Delaware and Hudson Railway

- Mohawk and Malone Railway

- New York Central Railroad

- Northern Adirondack Railroad

- Paul Smith's Electric Railroad

- Saranac Lake and Lake Placid Railroad

- Saranac Lake Street Railroad

- Union Depot

Source

- "Historic Resources of North Elba: Survey and Preservation Strategies" by Argus Architecture and Preservation, 1991.

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, November 14, 1969 1

The Fabulous History of Our Fabulous Railroads

David B. Hill, while Governor of New York State (1885 - 1892) described the Adirondacks as, "the nation's pleasure ground and sanatorium," and yet prior to the construction of the Adirondack and St. Lawrence Railroad in 1891-92, this region was for the most part inaccessible except to a comparatively few hunters and fishermen who were willing to undertake long trips by stage or buckboard or still longer and more arduous journeys through lakes and streams and over numerous portages or carries. An Adirondack Park had even been talked of (first by Verplanck Colvin in 1872) and even created (May 20, 1882) but there was no way for the people as a whole to get out and enjoy it. It was very much as if a great city had a park with a wall around it."

This is an accurate assessment of the transportation situation in the Adirondacks 75 years ago and points up one of the main reasons why the region was developed so slowly.

As early as 1807 the New York state Legislature authorized the building of a road from Chester, in Warren County, to Canton in St. Lawrence County, right through the center of the Adirondacks. This was known as the Old Military Road and was supposed to have been used for hauling military supplies in the War of 1812. However, the grades of this old road were so difficult that it was soon abandoned.

Another so-called military road was authorized in 1812 for opening and making a road be tween Albany and the St. Lawrence River. Called the Albany Road, this "highway" gave its name to Albany Lake, now Nehasane Lake. Supposedly completed in 1815, it soon fell into decay and disuse.

Still another actually built was an east and west route from Crown Point to Port Leyden (Lewis County), but again the grades were so great that reportedly only one vehicle ever passed over its entire length. Indicated on a few old maps, in some sections those people who are skilled in wood craft or engineering can still find traces of its location, but for the most part it has long since ceased to be more than a memory.

An even earlier mislabeled military route was enacted April 5, 1810, "to establish and improve a road from North West Bay on Lake Champlain to Hopkinton in the County of St. Lawrence." Its objective was to communicate with the road leading through the Town of Keene and other towns in Essex County. This existing road from Westport to North Elba, which had been opened several years earlier at private expense, already extended as far as the present Village Saranac Lake. An act passed in 1812 stated that previous appropriations had been entirely inadequate to open and improve the road, so obviously it was not usable at the time of the War of 1812.

Finally, in April, 1816 still another act was passed to complete the road and work was started at each end. Therefore, all evidence shows that the road was not built by soldiers and not finished in 1812, thereby refuting the claim that it was built for military purposes.

A more logical explanation for the persistent name is that it crossed the Old Military Tracts, which were set up by the State as bounty lands to reward men who were willing to serve as militia to guard the Canadian border. Parts of this road were later incorporated into the highway which went through West Harrietstown, Paul Smiths, McColloms, Meacham and then along the East Branch of the St. Regis River to St. Regis Falls and on to its terminus at Hopkinton.

Another Hopkinton and Port Kent road, known as the Turnpike, to distinguish it from the earlier route between the two settlements, was enacted in 1824. Incidentally, the commissioners were empowered to assess each town the road passed through on the Northwest Bay Road the sum of $75, which supplemented the State grant of $8,000 distributed over several years. After four surveys for the later road had been made, a route was selected which led from Port Kent to Keeseville, then northwesterly to Franklin Falls, Alder Brook, Loon Lake, Duane, Dickinson and on to Hopkinton. The distance was 74 1/2 miles of which over 50 lay through unbroken forests.

In 1829 the State appropriated $25,836 for this road and authorized a tax levy of $12,500 more on adjacent lands. Later the State loaned Clinton County $5,000 to build a road via Redford and Goldsmith's to join the Port Kent and Hopkinton Turnpike at Loon Lake; in 1832 it granted an additional $3,000 to complete this branch road.

For many years the Turnpike was a toll road and most of the steepest hills were planked. During the period from 1835 to 1860 an enormous amount of teaming was done over this road. These were the great days of the lumbering industry, the era when clearcutting the forests and subsequent fires in the slash left many of the Essex and Franklin County mountains and plains completely denuded.

Curiously enough, while the lumbering industry poured a great deal of money into such towns as Jay, Keene, Black Brook, Keeseville, Franklin and Duane, almost every one of the "big" lumbermen lost money and many of them died in poverty.

The same was true of most of the captains of the iron industry, who invested far more in mines and forges than they ever took out of them. In the palmy days of the Port Kent and Hopkinton Turnpike, especially in the Fall and early Winter, long lines of wagons and sleighs made their slow way eastward with heavy loads of wheat, corn, pork, hides (both of deer and domestic cattle), wool and potatoes from the comparatively fertile fields western Franklin, and eastern St. Lawrence counties, and returned with lighter but more valuable loads of fine flour, cotton cloth, tools and such groceries as could be afforded by those early pioneers. Port Kent, the eastern terminus, was an important little village, enjoying a lively prosperity quite different from its more modern quiet beauty.

Of more than passing interest is the statement in a Malone FARMER article that in 1802 it required six days to go from Malone to Plattsburgh on steer back, and in 1820 two days to travel from Moira to Ft. Covington, a distance of 20 miles. Moreover, the trip was made in June with a yoke of oxen and sled because the road was too bad for wheels. In 1840 letters and newspapers required from six to eleven days to reach Northern New York from Albany, and as late as 1857 Malone newspapers took two weeks to reach subscribers in Saranac Lake.

In 1838 a survey was made for a railroad between Ogdensburg and Port Kent, passing through the northeast corner of the Adirondacks. The project was soon dropped but later on portions of the survey were used during the construction of the Northern Railroad, connecting Ogdensburg and Malone.

In 1837 the Adirondack Railroad Company was franchised to build a road from the Adirondack Iron Works in Newcomb (Tahawus) to Clearpond in the Town of Moriah (Essex County). Nothing ever came as the result of that scheme.

Still later, in 1846, a combination rail and water route was concocted and given legislative approval. This particular engineering pipedream had a familiar itinerary: starting at Port Kent on Lake Champlain it was supposed to follow the Saranac River and Lakes, cut through to the Raquette River, then down through Long, Crotchet (Forked) and Raquette lakes. From there it was to head down to Boonville in Oneida County This grandiose project was elaborately outlined and publicized but nothing ever materialized.

The first railroad to come near the Adirondack Park was the Whitehall to Plattsburgh line, constructed in 1868 between the latter place and Point of Rocks or AuSable Station, a steamboat stop on Lake Champlain. This 20-mile section was extended to AuSable Forks in 1874 but never got any further.

A railroad spanning the entire distance from Plattsburgh to Whitehall had been agitated for years previously but HIP actual construction plans became the swirling storm cent or of a notorious political squabble which eventually and effectively killed the proposed undertaking.

THE ADIRONDACK RAILROAD

By far the most ambitious railroad project of the earlier era was the plan to put down trackage between Sackets's Harbor, on Lake Ontario, and Saratoga. Incorporated in 1848 and headed by some of the most prominent men in the country, this expensive effort over a 23 year period still carries all the elements of a fascinating drama. Highlighting the enterprise was the preparation of two surveys stretching from the upper Hudson Valley through the heart of the Adirondacks to the shores of Ontario. The northerly route, 182 miles via Raquette Lake and either the Beaver or Moose River, then along the valley of the Black River to Lake Ontario —was finally decided upon.

The estimated cost of $576,000 was softened considerably by the granting of an option to buy upwards of 250,000 acres of prime real estate for 5 cents per acre. To further sweeten the deal, this acreage was matched by private owners and all of it was declared exempt from taxation for an appreciable period.

If ever there was a railroad more needed or favored by the Sovereign State of New York, a railroad conceived and managed by energetic and influential men, it was this one—and yet the promoters' dreams were never realized.

After 30 miles of track had been built the company exhausted its capital, attempts to raise further money failed, subsequent receivership and reorganization got nowhere and in 1863, the property was acquired by New York Central capitalists and Dr. Thomas Cole Durant.

Durant, previously prominent in the planning and building of the Michigan and Southern, Chicago and Rock Island, Mississippi and Missouri railroads, was the most active advocate of the Union Pacific Railroad from the start of construction in 1861 to the driving of the last spike. During that period he was vice-president, general manager and acting president most of the time.

He immediately reorganized and renamed the company and gave its investors land mineral, timber and manufacturing rights. Its western terminus was changed to Ogdensburgh, its stockholders were granted complete tax-exemption for twenty years and its holdings were enhanced by the acquisition of the MacIntyre Iron Company at Tahawus

Although prospects were definitely rosy and in spite of Dr. Durant's well-known ability and abundant resources, only 60 miles of track — from Saratoga to North Creek — were ever laid. Black Friday of 1873 came up, British and American capital dried up, and the owners of thousand-dollar bonds had to settle for $210.00 each. Later the railroad was sold at foreclosure proceedings to William West Durant and William Sutphen for $350,000. Finally, in 1889, the line was signed over to the present owners, the Delaware and Hudson Company. Much of the original property gradually was acquired by corporations and private owners.

The Chateaugay Railroad

The first railway to cross the "blue line" and enter the mountains was the Chateaugay Railroad, which ran from Plattsburgh to Saranac Lake. The first train over the line was run on Dec. 5, 1887.

This road dates back to 1878, when legislation was passed in Albany "authorizing the construction and management of a railroad from Lake Champlain to Dannemora State Prison." Construction authority was delegated to the Superintendent of Prisons: all the work was done by convict labor. Not long after its completion in 1879, Smith A. Weed of Plattsburgh and a group of business associates needed an outlet for their iron ore being smelted at their forges at Popeville, near Lower Chateaugay Lake. They decided to lay a track from Lyon Mountain to Dannemora and thus connect with the line already running to that place. Soon afterward in May. 1879, they organized the Chateaugay Railroad Company and leased the Dannemora line from the State. On Dec. 17th of that year the first regular train went over the entire line and on Dec. 18th the first shipment of ore reached Plattsburgh.

The Chateaugay Railroad was later extended from Lyon Mountain to Standish, then to Loon Lake and finally to Saranac Lake in 1887. On January 1, 1903 the Delaware and Hudson Railroad Company bought the Chateaugay and broad-gauged it.

In 1893 the Saranac Lake and Lake Placid Road was put down and operated between the two villages. Fare for the 10-mile trip was $1.00. Like the Chateaugay this short line was also narrow-gauge but since three rails were laid, broad-gauged rolling stock bound for Lake Placid could be accommodated. This road was sold to the New York Central and eventually to the Penn Central.

Hurd's Road

The next railroad to penetrate the "blue line" was built in stages by the flamboyant timber tycoon, John Hurd. Entirely in Franklin County this line wound through the forest and entered the Park at Le Boeuf's, about ten miles south of Santa Clara. About 1882, Hurd, Peter MacFarlane and a man named Hotchkiss bought some 61,000 acres of land and already existing mills at St. Regis Falls. From that point they built seventeen miles of track to Moira, a station on the Northern Railroad (later the Rutland), which ran from Ogdensburgh to Malone.

Soon afterward Hurd became sole owner, chartered the Northern Adirondack extension Company and built another twenty miles of track — first to Santa Clara (named for his wife) and then to Brandon in 1886. The last link, the twenty-two mile section to upper Lake, was finished in 1889. The total length of railway, some sixty miles, was never much more than a logging railroad in Hurd's time.

Hurd's destiny was determined to a very large extent by his precarious relationship with the Dodge-Meigs Co., which later became the Santa Clara Lumber Co., unquestionably one of the few really important companies of its kind operating in the northern Adirondacks. The company, which started just after the Civil War with Titus B. Meigs, and Norman Dodge and George Dodge as partners, also had extensive interests in Georgia, Pennsylvania and elsewhere. Through a Henry Patton of Albany in the late 1880's the firm was introduced to John Hurd, who at that time controlled large tracts of timberland in northern Franklin County. Shortly afterward the interested parties were granted a 50-year charter under which they contracted to meet the following stipulations: "to make an earnest, determined effort to prevent and extinguish forest fires; to plant trees, grown largely in their own nursery; to ross (debark) pulpwood in their own mills and sell same; to utilize the so-called waste and sell it as chips for chemical pulp."

Capital investment was reckoned as 4,000 shares, with par value of $100.00 — of which Dodge, Meigs & Co., owned 2,200 shares and John Hurd, 1800. The company's operations were limited almost entirely to Franklin County, where it owned and cut over nearly 100,000 acres and supplied mills at St. Regis Falls, Santa Clara and Tupper Lake. Its principal products were soft and hardwood lumber, rossed pulp, wood clapboards and box shooks, hemlock bark, spruce and hemlock lath, and chips and fiddle butts — selected logs used in the manufacture of piano sounding boards.

Relations between the swashbuckling Hurd and his more sophisticated partners were none too cordial from the very beginning. Two years after the formation of the company hard feelings were created when Hurd installed foundation piers for an enormous sawmill (the Big Mill on the site of Municipal Park, Tupper Lake) in direct violation of an agreement that gave the company the right to choose the railroad terminus. After a great deal of conniving and legal maneuvering young Ferris Meigs acquired the title to property on which Hurd had already spent thousands to improve.

Old John was understandably furious at this skullduggery and the battle began. Hurd had borrowed large sums of money from the Franklin Trust Co., of Brooklyn on shaky security. Meigs, only 23 at the time, was given sole authority to handle the case for his part of the firm with instructions to get the money due them from Hurd but without revenge or profit. The latter apparently lost what little cool he had and became abusive but had to concede to a settlement. Final arrangements were made not by Meigs but by Mr. Dodge. who botched the deal and weeks of remedial work were needed to square it away formally to Dodge & Meigs Co. Apparently the firm had also been forced to cover notes on which Hurd had defaulted on previous occasions.

Even though Hurd lost out, no effort was made to exploit the wide-open opportunity to send him to the cleaners and Titus Meigs passed up an offer of $50,000 for the millsite.

This misfortune, plus the even more costly encounter with Webb, hastened the financial downfall of the old giant.

"Uncle John" Hurd, as the hard-driving, blustering and dynamic man was called, was a reckless speculator and much-talked-of person during his heyday in the region. After his twin disasters he returned to Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he died in poverty on August 5, 1913 at age 83 having "looped the loop of spectacular success as an Adirondack lumber-king," as Donaldson commented.

According to the publisher-editor of the Malone Farmer Hurd was unquestionably one of the most courageous and determined men who ever operated in the northern Adirondacks.

The thriving villages of Dickinson Center, St. Regis Falls, Santa Clara and Tupper Lake are actually monuments to his memory. With his associates he developed (clear cut) the lumbering industry in western Franklin County and did not rest until he had completed his Northern Adirondack Railroad up steep grades and over very difficult terrain. All this after he had passed his prime of life.

The building of Webb's "Golden Chariot Route" unquestionably contributed to the collapse of the Hurd Line, which was sold in 1895 to a syndicate which proceeded to extend the line across the Canadian border to Ottawa. This resulted in the eventual changing of its name to the New York and Ottawa. Through service was established in the fall of 1900. In 1906, at a foreclosure sale held in St. Regis Falls, the railroad again changed ownership. This time it became part of the New York Central system.

Even after the New York Central System took over from "Uncle John" Hurd and renamed it the New York and Ottawa, train travel in Winter was often anything but pleasant. For instance in the files of the Tupper Lake Herald for March 13, 1908 is the account of a blizzard that must have been a real doozer: "The old reliable New York and Ottawa, which has pulled through some bad storms had to succumb to the force of last Friday's blizzard. The train left Ottawa in the afternoon and struggled ahead until it stalled in the drifts between Dickinson Center and St. Regis Falls. The engine was detached from the train in an attempt to force a way through and it proved to be impossible to get it back again. The cars, stranded without heat, became frigid and the passengers suffered acute discomfort until after midnight, when two teams from Bishop's Hotel got through and took them back to the Falls. Thanks to this assist by old-fashioned horse-power the hapless passengers had a chance to rest and thaw out before their train was dug out and rolling again. It arrived in Tupper Lake at 2 P.M. — about twelve hours late."

However, the N. Y. & O. was not the only one to have trouble during that same storm. The south-bound New York Central train, due in Tupper at midnight was stalled near Beauharnois, P.Q. when it plunged into a huge snowbank in which a freight train had previously suffered the same fate. The snow was five feet deep on the track and the wind was fierce. The trains were soon unable to move in either direction. A snowplow was sent to scene and the freight cars were finally hauled out one at a time. The passenger train reached Tupper at 2 P.M. Sunday. If you had to travel in the Winter in this region back in 1908 you had to go by train because there was no other way.

Undoubtedly Hurd's greatest achievement was creating the village of Tupper Lake. Before his time, there was nothing much in that vicinity but pasture land and clearings belonging to the early settlers. But when Hurd built the Big Mill on the site of the present Municipal Park, the place boomed and prospered as a lumber town. The lively, rough.

looking settlement was almost entirely wiped out by the holocaust of July 29-30, 1899. when 169 buildings were reduced to ashes within a span of only three or four hours. The first proved to be the proverbial blessing in disguise because more substantial and attractive structures were gradually built as the village recovered its confidence and sense of purpose.

Webb's "Golden Chariot" Route

Aside from the obvious desirability of opening the Adirondacks for the enjoyment of the general public, this region represented the only route not already pre-empted for trade between New York City, Canada and the Northwest. Furthermore, there has always been keen competition between different parts of the Dominion as shipping points and communication centers. The only open ports in Winter are Halifax and St. John, Nova Scotia and to reach these harbors from the Canadian Northwest necessitates a long haul by railroad whereas a shorter route would place Canadian commerce within direct contact with the port of New York. Efforts to provide such a mutually advantageous route were given top priority on both sides of the Border in the 1880's and '90's.

At that time the profitable carrying trade was about equally divided between the Delaware and Hudson and the Rome, Watertown and Ogdensburgh Railroads. The latter line avoided the formidable Adirondacks by using a longer route which skirted its western slopes, while the D. & H. monopolized the narrow Champlain Valley.

Therefore, any other railroad company seeking Montreal trade would necessarily have to build directly through the mountains, a tremendous undertaking.

By 1890 there had been much newspaper agitation in metropolitan papers on the desirability of such a road and the fact that the New York Central was not in direct competition with the smaller lines. Persistent pressure became so strong that the Central took the preliminary steps toward building a road which was to parallel the Rome, Watertown and Ogdensburgh in whole or part. Such was the general situation when Dr. W. Seward Webb, the son-in-law of William H. Vanderbilt, stepped into the spotlight.

Webb, who had always been an Adirondack addict and sportsman, was a charter member of the Kildare Club, north of Tupper Lake, as well as the owner of some 115,000 acres in Herkimer and Hamilton Counties, became enthusiastic over the possibility of constructing the desired railroad even though his father-in-law did not share his interest nor furnish financial backing. The New York Central, however, showed considerable interest in the proposed railway at that time.

The projected railroad depended primarily on the acquisition of several smaller lines, the first of which was the Herkimer, Newport and Poland Co., constructed in 1883. Next he annexed the Mohawk and Northern Company, opened for operation in 1890. By merging these he now headed the Mohawk and Adirondack Railroad, which later was expanded into the Mohawk and Malone Railroad Co., made possible by the building of the Remsen-Malone section in less than two years.

Since the New York Legislature, because of skullduggery and delaying tactics on the part of lobbyists and lawyers for the rival D. &. H., refused to provide any help, Webb went ahead anyhow and provided the necessary money, men and machinery.

In early 1891 George C. Ward, an engineer who knew the Adirondacks well, was hired to make a survey of the route from Remsen to Paul Smith's and from there to Malone. In the reconnaissance party was Lem Merrill of Merrillsville, who was even better acquainted with much of the projected right of way than was his boss. Lem walked the entire length of the line during the surveying operation.

At that point the Rome, Watertown and Ogdensburgh agreed to lease its line to the New York Central, which thereafter had no official or financial interest in the new enterprise.

Webb's next move was to negotiate with John Hurd who, though hard-pressed for money, refused the former's offer of $600,000 - considerably more than the poorly-built line was worth. Dickering broke off and Webb spent the Summer in Saranac Lake in order to take personal charge of his project.

Hurd late reconsidered, a deal was made and papers were ready for the signatures the next morning. That night, however, a Mr. Payne of the Pope-Payne Lumber Co., visited the horse-trader type Hurd in his New York hotel and offered to raise his (Webb's) bid by $50,000 if Hurd would give him a short-term option. The next day, instead of signing the papers, the wily "Uncle John- just dropped in to tell Dr. Webb that the deal was off once more.

Later that morning Payne appeared in Webb's office and tried to sell him the option for a sizeable profit. The furious Webb told him in well-selected language exactly what he thought of the pair and informed them that he (Webb) would parallel the Hurd road within a year — and kept his word.

It was now full speed ahead as Webb's crews went into action at both ends simultaneously. The work was pushed feverishly both Summer and Winter until completion. Many seemingly insurmountable problems were encountered. Summer rains made such bogs of the supply roads that in certain southern sections six-horse teams sometimes arrived with a load consisting of one bale of hay — not even enough to feed the team. Backpacking was often required to feed men and horses in some of the more distant camps. Since it was impossible to bring in modern equipment, progress was frequently both exasperatingly slow and expensive. Building rights across the restricted Forest Preserve lands were gained by swapping right-of-way acreage for other land of equal or greater value.

Negro workers, recruited in Tennessee, also compounded the difficulties. Some arrived barefooted and with only overalls for clothes. Even after they had been outfitted properly, many of them still didn't like the climate and wanted out. Some did and upon reaching New York started an editorial agitation in the Yellow Sheets (tabloids) which led to unjust criticism of Webb, who had had nothing to do with the hiring of the men, that having been done by the contractors. A would-be blackmailer was trapped in Boonville by use of a primitive dictograph, a stovepipe hole in the ceiling of the hotel room.

An example of the loyalty engendered by Dr. Webb was demonstrated in early 1892, when the northern operation reached Loon Lake. There Chief Engineer Roberts received a telegram from Webb stating that he (Webb) had promised to build a temporary spur line to the Loon Lake House so that President Benjamin Harrison could take his invalid wife to Chase's. The job had to be finished by the next day. After protesting that it could not be done in that short time, Roberts started work immediately. His crew graded and put down a mile of track in 24 hours and everything was ready when the special train pulled in.

On another occasion one of Webb's detectives notified him that the engineers and draftsmen at Herkimer were loafing and had not reported for work until late morning. The Doctor then asked, "What morning are you talking about?" The man told him. "Oh," said Webb, "you should have been there the night before!"

There were many earbenders told about the building of the road. One of the most characteristic featured the frenzied rivalry between the crews of St. Regis Indians on the northern section and the Negroes working to the south. Daily progress reports were posted each night and the men worked furiously to outdo each other. One resourceful boss got extra effort out of his men by placing a keg of beer far enough ahead to guarantee a big day's work and then let them celebrate when they had reached that goal.

Finally, on October 12, 1892, about a half mile north of Twitchell Creek Bridge, the two ends were joined and the last spike driven. This honor was given a young assistant engineer, a better engineer than track-layer, who missed his target a round dozen times before he finally connected — much to the disgust of the assembled Negroes and Indians.

While work on the Adirondack and St. Lawrence road, as it was later known, was nearing completion, Webb concentrated on a section even farther north, the Malone to Montreal phase. Completed as far as Valleyfield by Jan. 17, 1892 this line was extended to Coteau, where it connected with the Grand Trunk, later called the Canadian National, Starting on Oct. 24, 1892, when the Herkimer and Malone line was placed in service, through trains were run from New York City to Montreal via Malone and Coteau.

On June 1, 1898 Webb entered into an agreement whereby the New York Central, now actively interested, took over the operation of this line without sharing in its profits or losses. This pact continued until Jan. 1, 1905, when the Central bought all the outstanding capital stock of the Webb route, and the builder retired from his last association with an enterprise which he had brilliantly and successfully placed in full operation within eighteen months from the start of the survey. It is doubtful if such a record and under such almost overwhelming difficulties has ever been duplicated.

The End of the Railroad Era

Throughout the nation but particularly in the thinly populated regions such as the Adirondacks the railroad industry has suffered from the progress of the times. From the days of the Great Depression in the '30's down to the late 1950's the companies started a systematic program to abandon their more economically anemic branch lines along with curtailment or even cessation of passenger service.

Although most of the lines were generously subsidized, they still could not—- and in many instances did not make any serious effort to counter the growing competition from the trucking business. All too often the owners of the iron horses indicated a deliberate and sustained attitude of the public be damned when the customers began to complain loud and often about the steady deterioration in the services provided for both passengers and shippers.

A clear example of the degree of decline is furnished by the June 20, 1913 issue of the Tupper Lake Free Press which carried the schedule of the Adirondack Division of the Central plus these noteworthy remarks: "To older residents who listen In vain for the lonesome sound of a steam locomotive whistle echoing through these hills, it recalls an era when 90 per cent of the travel in and out of the North Woods was by rail, and the arrival of each train at Tupper Lake Junction touched off a busy scramble, with scores of passengers boarding or leaving the cars, express crews bustling around and "busmen" for the Altamont. the Iroquois and the Holland House vying for fares."

There were six trains scheduled north and six south daily back in 1913. The Montreal Express pulled in at 5:05 a.m. It was followed at 6:15 by the Adirondack Express. At 1:15 p.m. the Adirondack Local rolled in at 5:05 p.m. the Adirondack and Montreal Special and at 7:18 the Tupper Lake Local was due. The southbound parade was equally impressive.

Daily freight trains added to the traffic which kept the steel bright on the Adirondack Division just prior to World War I.

Fifty years later there were only two passenger trains serving the Tri-Lakes area. One left Lake Placid at 9:30 p.m. and reached New York City at 7:15 the next morning. This was the only passenger train going south on the Division. The only northbound train left New York City at the ungodly hours of 11:15 p.m. (for those riding in the daycoach) and arrived in Lake Placid at 9:55 a.m.

The process of gradually working toward the elimination of all traffic to the North Country area began about 1950, when the New York Central petitioned the Public Service Commission [PSC] to remove some of its trains.

The next phase featured the closing down of the stations. Those between Lake Clear and Malone were closed in May, 1956 and later torn down. Before the final closing of the Gabriels station a few had remained open during the summer months, but closed in the winter. In the fall of '56 a Kentucky salvage company tore up the tracks from Malone to Gabriels and thereby removed all reminders of railroad traffic to this part of the mountain.

After 1956 Lake Clear Junction became the freight center and ticket office for the eliminated stations. Mail for the surrounding villages was unloaded there and carried the rest of the way by truck. In 1959 the P.S.C. allowed the Central to drop the two day trains but made them keep the night trains in operation. That same year the Lake Clear station was closed and its business moved to Saranac Lake. The Central continued its efforts to discontinue its passenger service completely but, even though it succeeded in modifying its service each time, it could not get permission to pull out altogether. In 1961 the freight office operation was moved to Tupper Lake, where it still functions.

Residents of the Tri-Lake area did not hesitate to express their concern and even indignation about the obvious objective of the railroad officials. Area chambers of commerce fought a sometimes bitter delaying battle in order to protect their vested interests and growth potential, which is predicated upon good transportation facilities. Public hearings were held in Saranac Lake and other communities at a cost of several thousand dollars each in order to force the railroad to stay in operation at least until the Northway was completed.

The trend of the final meetings illustrated a lack of any real interest on the part of the railroad to seek any solution besides discontinuance. Its method was to make its so-called service so bad that it was used less and less. Eventually the people in the area supposedly being served no longer really cared whether or not the railroad pulled out. Then came the end of an era: on April 28, 1965 the last passenger train, with Floyd Fullerton at the throttle of the big diesel, pulled out from Saranac Lake station.

The Central then proceeded to cut down freight service and refused to handle shipments of less than carload bulk. This especially embittered the area merchants but the New York Central and later the Penn Central, its successor, apparently were not interested in trying to increase the freight loads through promotion and improved service.

At present one freight train a week comes through on a rather casual schedule, depending on the nature of the cargo. The former Sunmount State Hospital, Ray Brook State Hospital and several area firms in Saranac Lake and Placid are still being supplied wholly or partly. But there are strong rumors and stronger indications that the Penn Central will end its operation in the fairly foreseeable future. Railroading, particularly passenger traffic, is no longer a paying proposition in most of the nation.

When the Penn Central finally does go, a great deal of glamour of a sort will go with it. The railroads played such a significant part in the development of the region that their passing will be sincerely missed, — at least by those who rode the trains in their heyday. The sound and smell of escaping steam, the waving of the brakeman's signal lanterns, the "All Aboarrd" of the conductor alter he had consulted his vest pocket Hamilton watch, the slow pumping off the well-greased driveshafts, the whirling and grinding of the big wheels as they sought to get traction; the slightly nauseating odor of the plush seats, the ubiquitous orange and banana peels, the newspaper and candy "butcher," the solicitous conductor, the cinders and smoke billowing in from the open windows — each is part and parcel of a composite pattern which will linger long in the memories of the older North Country generations.

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, April 2, 1972

Penn Central Chugs to Rescue Of "Coal Starved Drug" Center

RAY BROOK — There is probably more railroading going on around Saranac Lake per square yard than anywhere in United States.

Strangely it may signal the end of another era and curtail the amount of gross tonnage hauled in here by Penn Central in its bid to end rail service entirely to the Adirondacks.

The snow plow with its double diesel locomotive, made another laborious run to Ray Brook yesterday which took the entire daylight hour span between 6 a. m . and 6 p. m. just passing through the village.

The old red railroad plow which was lettered "Ray Brook or Bust" on the front was attempting to get to the State Rehabilitation Center to shift three coal cars which were on a siding over to the bunker area in back of the powerhouse where they could be unloaded.

This morning the Diesels were parked on the Big D siding of the former N.Y. Central Freight station with the empty coal cars and a chemical car facing toward Utica and it was presumed that the mission was accomplished.

Sunday morning the plow played to a full house between the Saranac Lake passenger station and the Pine Street crossing, a distance of less than half a mile but which consumed several hours . The dogged progress could be measured by inches in some places. Several railroad crewmen were consigned to pick and shovel duty loosening the ice which threatened to derail the plow as it crept forward.

As the Ray Brook terminal the train was awaited with considerable patience which was understandable since the last time the plow was able to get through was about 6 weeks ago.

Bill Allen, a Chateaugay Railroad historian, said that the plow had been off the tracks about 34 times in its last trip from Utica. He said he had looked it over trying to find the date of manufacture and came up with an estimate that the heirloom was 100 years old.

The Ray Brook Rehabilitation Center is currently converting to oil and the first tests of the new system will be held this week.

Coal which was running dangerously low at the institution would have required its being hauled in wheelbarrows from the cars on the siding if the Penn Central unit had not gotten here when it did.

As usual, the train progress was studied by hundreds of children during the day which constituted an educational highlight in an otherwise dull and cold Sunday.

Trains, trains, trains!

The Adirondack railroads that opened the mountains to settlement and tourism were the focus of a conference at the Adirondack Museum

By Lee Manchester, Lake Placid News, October 18, 2002

Railroads through the Adirondacks were more than just a pretty ride; they were indispensable in opening up the mountains to settlement, industry and tourism. Without them, most of the territory within the Blue Line would have been unknown and unknowable to all but a few of the hardiest explorers until the mid-20th century explosion of road building.

That’s why last Thursday’s conference on regional railroad architecture and heritage at the Adirondack Museum was so important, drawing more than 75 participants from all over northern New York state, some of them preservationists, some of them just train fans.

Coordinated by Adirondack Architectural Heritage — also called AARCH — a nonprofit historic preservation society based in Keeseville, the “All Aboard!” conference was the brainchild of Jane Mackintosh, a curator at the Adirondack Museum.

“The railroad was crucial in the development of the Adirondacks,” said Bill Johnston, AARCH president, in opening the conference. “Its role in the development of industry — particularly iron — as well as tourism and the Saranac Lake cures cannot be overestimated.

“Today, with most of the live, working Adirondack railroad lines abandoned, new kinds of activity draw our attention: preservation of the old depots, and redevelopment of the old rights-of-way for scenic train lines and ‘rail trails.’ ”

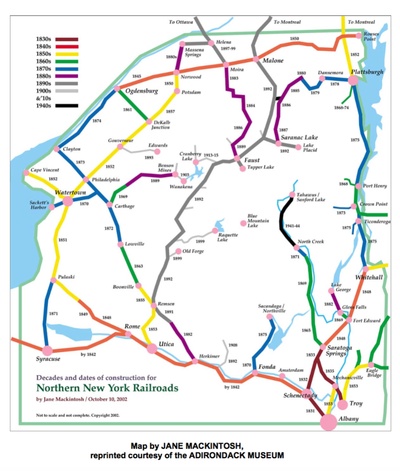

Mackintosh provided a historic overview of the development of railroad service in the Adirondacks, illustrating her address with a map that some conferees thought was probably the first comprehensive diagram of all the rail lines ever built in the region.

Several early attempts at settling and developing the Adirondacks were either stifled or failed altogether for lack of ready transport. Timbuctoo, a mid-19th century agricultural community of free African Americans in North Elba township, was said to have disintegrated after just a few years in large part due to the farmers’ inability to ship their produce to market.

Early efforts to mine pig iron in North Elba, Adirondac and Tahawus faltered and died for lack of a railroad. The mines near Ticonderoga were developed only because a rail bridge was built nearby across Lake Champlain into Vermont.

The iron-mining communities of the Au Sable Valley were not developed to their full potential until extended railroad lines gave them quick access to the lake and the main north-south track built by the Delaware and Hudson Railroad.

Both Adirondack tourism and Saranac Lake’s health-resort industry also depended heavily on the building of the railroad into the Adirondacks, Mackintosh observed. The rail line up from Utica, built in 1892, employed “heroic engineering to overcome barriers to railroad construction presented by the land,” the curator said.

When that line was connected with the railroad to Malone, the Adirondacks were as fully connected to the world, from Montreal to New York to Buffalo, as any other American region.

“The railroad connected once isolated towns,” Mackintosh said, “and it gave them trade access to the outside world.”

What remains of the “heroic engineering” work of the Adirondack railroads, in many places, are only the depots that formerly welcomed the trains into our mountain communities. Engineer Michael Bosak addressed last Thursday’s conference on the many varieties of adaptive re-use that have transformed these depots while preserving them as links to our heritage:

-

In Plattsburgh, the restored 19th century D&H station contains a passenger platform

served by the Amtrak line between New York City and Montreal, but most of the

interior space is dedicated to offices. - In Au Sable Forks, the old D&H depot is now a restaurant.

-

Since 1967, the Lake Placid train station has been used as a community museum by

the North Elba-Lake Placid Historical Society.

“Of course, there’s nothing that helps the restoration of a historic railroad station like the return of a historic railroad,” Bosak observed.

The creation of the Adirondack Scenic Railroad, both in the southern Adirondack Park between Old Forge and Utica and in the High Peaks region between Saranac Lake and Lake Placid, has spurred the restoration of historic train depots in Thendara and Remsen and given life to the already restored stations on the northern line.

Mary Hotaling, executive director of Historic Saranac Lake, told the “All Aboard!” crew about her organization’s restoration of the 1904 Union Station that now serves as the northern hub of the Adirondack Scenic line.

Passenger service into Saranac Lake and Lake Placid on the D&H and New York Central lines ended in 1965, while freight service lasted another seven years until 1972.

“At that point,” Hotaling said, “the (Saranac Lake) station just sat there and sat there, deteriorating.”

In 1994, Historic Saranac Lake decided to call a meeting to see what could be done to restore the depot. The organization’s interest came at just the right time. A new village manager and a new development director for Saranac Lake had just started their jobs; both had loads of energy and lots of fresh ideas.

Rob Camoin, the development director, was familiar with ISTEA (often pronounced like “ice tea”), the Intermodal Surface Transportation Enhancement Act of 1992, which provided federal money to rebuild transportation-related facilities across America. ISTEA gave most of the money for the Saranac Lake depot project, but 20 percent of the project’s cost had to be raised by Historic Saranac Lake in matching funds.

“(State Senator Ron) Stafford kicked in some money from discretionary funds,” Hotaling recounted, “but Historic Saranac Lake had to finance the remaining $30,000, which was very difficult for us as a small organization.”

The impetus for restoring the depot was more than just the abstract appeal of restoring an old industrial facility. Rumors abounded that the new Adirondack Scenic Railroad, started in 1992 out of Old Forge, was considering the restoration of service between Lake Placid, Saranac Lake, and Tupper Lake, eventually connecting the High Peaks all the way back down the 119 miles to Utica. It seemed important that Saranac Lake ready its historic depot if the train was going to return.

The actual restoration of the depot may have played a part, in turn, in the actual revival of the Adirondack Scenic Railroad’s Sara-Placid run.

“We didn’t know for sure whether the train was going to come back or not,” Hotaling said, “but the fact that the depot was there was evidently a critical part of the railroad coming in.”

“You’ve hit on the $64,000 question — or the $64 million question, today,” remarked Bosak to Hotaling, “which is what to do with a restored railroad station once it is restored.”

“I believe that the best use for a restored building is the use for which it was designed,” Hotaling responded.

Steve Engelhart, AARCH executive director, followed Hotaling with a survey of a few recent railroad depot restorations in the Adirondacks, along with a rundown of several depots desperately needing attention.

Engelhart opened his talk with a reminiscence of riding the night train from Italy to Austria once as a child, during which he had one of the most restful night’s sleeps he’s ever experienced.

“It was something about the rhythmic clack of the rails,” Engelhart recalled, “the wonderfully comfortable berth, and the gentle, back-and-forth rocking of the train.

“I think I’ve been trying ever after to recapture that night’s sleep.”

Several of the recently restored stations reviewed by Engelhart are part of overall historic restoration projects, like the depots in Thendara, North Creek and Riparius.

In other communities:

-

In Westport, the restored train station has been the home of a small regional theater

company since 1979, a function that does not interfere with the depot’s role as an

Amtrak passenger platform. -

The Port Henry station, which also hosts passengers waiting for the Amtrak train,

houses the community’s senior citizens center as well as part of Moriah township’s

mining heritage complex. -

In Dannemora, the 90-year-old train depot was purchased in 1991 by the village

government. Situated in the center of the community, as train stations so often were,

the converted depot was an ideal candidate for use as the village’s office building. -

Several Adirondack and North Country historic railroad stations, however, were in

bad shape and needed attention, according to Engelhart: -

Lyon Mountain had rail service from 1873 to 1970. The existing train depot, built in

1913, needs friends — and friends it has found. A group called Friends of Lyon Mountain has purchased the depot, hoping to use it someday for a mining and railroad museum. In the meantime, the Friends have put a new roof on the structure and restored the foundation to keep it from disintegrating any further. - In Rouses Point, the old Romanesque Revival brick depot, built in 1877 but moved from its original location, is in need of help.

- The wooden Crown Point station, built in 1868, is “just hanging on for dear life.”

Any amount of energy spent on restoring these structures would be valuable, Engelhart said. Repairing roofs and shoring up foundations would keep the endangered depots from slipping any further toward disintegration.

“Some restorations take years,” Engelhart said, “while others are more modest.There isn’t really any one way of doing it.”

Engelhart said he had one pleasant surprise in his whirlwind tour of existing railroad stations in the area: The West Chazy passenger terminal, built in 1907, which has been converted into a private home by a pair of real railroad enthusiasts.

“They’ve got a model railroad running through their raised-bed garden,” Engelhart said. “They’ve moved a caboose onto the site, which one of the owners uses for a shop. She calls it ‘The Crystal Caboose.’ ”

At lunchtime, the conferees gathered in the Railroad Room of the Adirondack Museum, which houses a luxurious 19th century Pullman car, the complete railroad depot from Kildare, the train watchman’s shed from Gouverneur, the horse-drawn carriage that met the trains at Raquette Lake and the benches from the Faust station outside Tupper Lake.

It was in that setting, with train-whistle sound effects echoing melodically in the background, that the keynote speaker gave his address. J. Winthrop Aldritch, the state’s deputy commissioner for historic preservation, said, “With only the D&H line along Lake Champlain running now, it may seem that railroads are things of the past here, but it need not be so.”

Aldritch noted that registering the entire line used by the Adirondack Scenic Railroad as a historic district, along with several other old depots and two antique railroad bridges along the Au Sable River, had helped more people become better aware of the railroad’s significance to the Adirondacks, and had also made it possible for restoration funds to flow to projects that needed them.

“There is so much more out there that could benefit from such listing and from the associated documentation,” Aldritch said, “I want you to consider this a call to you all.”

Several kinds of restoration grants are available to properties that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

“These grants have proven, time and again, to be the lever by which these projects have been started,” Aldritch observed, “but we can’t make these grants if you don’t apply for them.

“My advice to you is, seize the day. You have people in office now who are sympathetic to your interests. Do not let this opportunity pass without using it to your advantage.”

When the conference reconvened in the Adirondack Museum auditorium, the program shifted gears. Where the morning’s agenda focused on historic restoration, the afternoon’s speakers considered the actual operation of the Adirondack’s railroads, both historic and contemporary.

The first afternoon speaker, northern New York social historian Amy Godine, introduced an oral history project she has been researching, “Working on the Railroad.” She and museum curator Jane Mackintosh have been traveling around the Adirondacks over the last few months, talking with people who’ve actually worked on the railroads running through the North Country.

“Most railroad histories focus on corporations, economics, big wigs,” Godine said. “You’ll look in vain for stories of the gandy dancers who pounded down the rails.”

Godine spoke lyrically of the lives of the men (primarily) who worked the railroads that opened up the Adirondacks — including the rigid pecking order that prevailed on the trains and in the yards.

“Engineers all wore black suits and chewed cigars and were older than Christ,” Godine said, recounting what railroad workers had told her, “and thought they were God himself.”

Godine introduced a panel of three railroad old-timers: Bud Bentley, a brakeman on the D&H; Gene Corsale, a retired D&H conductor who now volunteers on the restored Upper Hudson River Railroad; and Larry LaFarr, a former engineer and current Upper Hudson River volunteer.

“Sometimes it was just work, but sometimes it was something more,” Godine said about working the railroad. “It was thrilling.”

The men, however, recalled their careers in rougher, more utilitarian terms.

“My foreman used to tell me, ‘Just because you bring your lunchbox don’t mean this is a picnic,’ ” recalled Corsale.

Finally, four people responsible for rebuilding three historic railroads in northern New York talked about how they did it:

- Peter Gores, general manager of the Adirondack Scenic Railroad in Thendara;

- Ron Crowd, founding director of the Batten Kill Rambler in Cambridge;

-

Tim Record, general manager of the Upper Hudson River Railroad in North Creek,

and - Wayne La Mothe, Warren County’s assistant planning director, who’s put together a multi-county, multi-community program to develop the entire corridor along which the Upper Hudson River Railroad runs.

“Running a restored railroad is the hardest job I’ve ever had, bar none,” Gores said.

All four discussed the operations of their railroads, much to the delight of the portion of the conference audience made up of railroad enthusiasts. By the end of the day, “trainheads” and preservationists alike had a much better sense of the full scope of their subject, thanks to the conference Mackintosh had put together.

Would there be another?

“I certainly hope so,” Mackintosh replied, enthusiastic applause following quickly upon her response.

Plattsburgh Sentinel, June 25, 1886

Adirondack Enterprises.

From the Malone Palladium.

School Commissioner Wardner is spending a week in this vicinity, visiting schools. He informs us that in a recent consultation with Mr. Hurd, of the Northern Adirondack Railroad, the fact was stated that on the evening of the fifth of July the first Pullman sleeper will start from New York for Paul Smith's station. It will come over the D. & H. C. R. R. to Rouses Point, thence over the O. & L. C. R. R. to Moira, and thence over the N. A. R. R. to destination —arriving at about 11:30 A. M., July 6th. It is a short hour's drive from this point, over a good road through the woods and along the river's bank, to Paul Smith's, so that the passenger who leaves New York at 6 p. m. one day may dine at one o'clock the next at this famous hostelry. Another four miles brings one to Mr. Wardner's at Rainbow. Returning, the car will start at two P. M. each day—arriving at New York early the next morning. This arrangement will save visitors a stage ride of over 40 miles as compared with existing facilities for ingress to and egress from these localities, and will permit them to make the entire journey without change of cars. It will enable them in returning to defer starting to a time of day five hours later than is now necessary and will save them $2.10 in fare. The car will run daily each way during the entire season, and is expected to attract all the New York travel bound for Paul Smith's, Wardner's, the Saranac country and Loon Lake—though the travel to the latter point will doubtless be diverted later in the season to the Dannemora and Chateaugay railroad, which is now building. All the hotels in this section will have railway ticket offices and have on sale tickets from their doors to New York city.

Paul Smith's station is to be the southern terminus of the Northern Adirondack railroad. It will soon be given some other name, and is intended to be quite a village. It is at this point that the lands of Hurd & Hotchkiss and Ducey & Backus join. The two firms are working in harmony to lay out quite a village here. The latter has already surveyed 160 lots and directions have been given by the former for similar platting of its lands. Streets will be established and a hotel is also to be built, containing sixty sleeping rooms. It will be heated by steam and will be first-class in all of its appointments. The location is a delightful one. Its elevation is about 1,600 feet above the sea, there is an unbroken wilderness on every side, and mountains surround it. The air is pure, the water abundant and excellent, and the view fine. [It] is predicted by men who ought to know it the place will in time become as popular and as much frequented as a winter resort as Saranac Lake now is.

The extension of the narrow gauge Dannemora and Chateaugay Railroad from Mine Eighty-One, a distance of 16 miles to Loon Lake, is being pushed rapidly. Over five miles of the route are already graded. The enterprise is undertaken principally enable the Chateaugay Ore and Iron Co, to extend its charcoal burning to the farthest limits of its possessions. No lover of the woods can regard with pleasure the prospect of devastation and desolation that operations of this kind threaten, but great enterprises cannot defer much to sentiment, ore must be mined and charcoal must [be] had to convert it into iron. It is, however, satisfaction to know that one of the principal owners of the road has solemnly promised that it shall never go to exceed five or six miles south of Loon Lake. Its terminus for the present will be at the northern end of Loon Lake—about two miles from Ferd. Chase's. An enterprise auxiliary to the railway is the construction of a wagon road along the west shore of Loon Lake to Mud Pond and thence to the old Oregon road. The distance is about six miles and the grade nearly level. This new road will avoid a long, hard hill and save two miles in distance in going from the railway terminus to Wardner's, Bloomingdale, Saranac Lake or Paul Smith's. It is being built by subscription—the sum of $2,600 having been pledged therefor. Chase gave $300, Paul Smith the same, Isaac Chesley $175, and others in proportion. This road will compete with the N. A. R. R. for the Adirondack travel and also for the freights of the resorts and villages in that section. It is expected that trains will be running over the road before the first of September.

Plattsburgh Sentinel, August 2, 1889

From 1872 to the present date, 439 miles of railroad have been constructed in counties of Essex, Clinton, Franklin, St. Lawrence, Jefferson and Lewis, as follows: Delaware & Hudson Canal Co., from Ticonderoga to Rouses Point, 91 miles; Ticonderoga to Lake George, 5 miles; Crown Point to Hammondville, 8 miles; Plattsburgh to Saranac Lake village, 73 miles; Bombay to Moira, 9 miles; Port Henry to Mineville, 7 miles; Northern Adirondack to Paul Smith's Station, 36 miles; Carthage and Adirondack to Oswegatchie, 42 miles; Fort Covington to Norwood, 40 miles; Utica & Black River, Boonville to Ogdensburg, 99 miles; Carthage and Saokets Harbor, 29 miles.

Comments

Footnotes

1. Most of this material was later included in DeSormo's Heydays of the Adirondacks, published in 1974