The Saranac Laboratory, 2010

The Saranac Laboratory, 2010  The Saranac Laboratory, 1907 The Saranac Laboratory: A Landmark from the Dawn of Science

The Saranac Laboratory, 1907 The Saranac Laboratory: A Landmark from the Dawn of Science

"The sanatorium represents what we know about tuberculosis. The laboratory represents what we do not know, but must find out." —Dr. E. R. Baldwin, 1924

The remarkable story of the Saranac Laboratory begins with its founder, Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, who came to the Adirondacks in 1873, seriously ill with tuberculosis. Here his health improved in the mountain climate.

After seven years and repeated attempts to return to New York City, all with bad effects on his health, Trudeau built a winter home in Saranac Lake, and founded the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium to care for incipient cases of tuberculosis among the working poor.

On March 24, 1882, in Germany, Dr. Robert Koch read his paper, “The Etiology of Tuberculosis,” with its startling conclusion that the disease was caused by an identifiable organism, the tubercle bacillus. Trudeau read abstracts of the paper in medical journals, and it excited his imagination. C. M. Lea gave the doctor a Christmas present of “a very full translation,” hand-written in a copy book. Wrote Trudeau, “I read every word of it over and over again.”

Trudeau Doctors, 1951: Front row, Drs. Vorwald, F. B. Trudeau, Packard, Meade, Leetch, unknown; Middle row, Drs. Brumfiel, Bristol, Coates; Back Row, Drs. Wolinsky, Wright, Pratt, Mr. Roy Dayton. Adirondack Daily Enterprise, June 30, 2007

Trudeau Doctors, 1951: Front row, Drs. Vorwald, F. B. Trudeau, Packard, Meade, Leetch, unknown; Middle row, Drs. Brumfiel, Bristol, Coates; Back Row, Drs. Wolinsky, Wright, Pratt, Mr. Roy Dayton. Adirondack Daily Enterprise, June 30, 2007

Near the back of the laboratory, February 1907,

Near the back of the laboratory, February 1907,

Dr. Twichell, Dr. Price, Victor Hugo, Dr. Kinghorn, Dr. Baldwin, Dr. Trudeau.

Courtesy of the Adirondack Experience.

Convinced by Dr. Koch's logic and enchanted by the possibility of a cure, Trudeau determined to learn how to stain and recognize the tubercle bacillus under a microscope in order to try Koch’s experiments for himself. Trudeau spent several days in Dr. T. Mitchell Prudden’s makeshift laboratory in New York, struggling through the difficult process until he became proficient enough to work alone.

Near the back of the laboratory, February 1907, unknown gentleman in top hat, cow, Victor Hugo, Dr. Twichell, Dr. Price, Dr. Kinghorn, Dr. Baldwin, Dr. Trudeau.

Near the back of the laboratory, February 1907, unknown gentleman in top hat, cow, Victor Hugo, Dr. Twichell, Dr. Price, Dr. Kinghorn, Dr. Baldwin, Dr. Trudeau.

Courtesy of the Adirondack Experience.

“In the fall of 1885, as soon as I had equipped my little laboratory-room,” wrote Trudeau, “I began to work.” At first he used his eight-by-twelve foot home office. Since the house was lighted by kerosene and heated with wood, “on very cold nights the doctor often had to get up and replenish the fuel,” noted historian Alfred Donaldson. “These quarters were so cramped … ” Trudeau said, “that I soon built a little addition off my office, and this became the laboratory in which I worked until … 1893.”

Science

The extraordinary cold mountain environment in which Dr. E.L. Trudeau was working demanded that he improvise special equipment to maintain the constant high temperature needed for germs to grow. The heat also had to be kept up for a long time compared to “any of the disease-producing organisms discovered before it.” After many attempts, Trudeau became “the second experimenter in the country” to grow a pure culture of the tubercle bacillus. “With these cultures I repeated all of Koch’s inoculation experiments,” and then “began making original ones.”

In December of 1892, young Dr. Edward R. Baldwin from New Haven [Connecticut] applied for entry to the sanitarium. Trudeau wrote “When asked what made him think he had tuberculosis, he quite floored me by his answer: that he had used his microscope and knew he had it … At my invitation he came to the Laboratory the day after he arrived in town and offered to help me there in any way.”

“For years Baldwin would carry his bundle of the literature over to the doctor’s house in the evening,” Dr. Allen K. Krause remembered, “and there read to him what was going on in tuberculosis, particularly in Germany,” and Trudeau would tell him what was happening in France. “This pair formed an almost ideal combination for scientific work.”

Late in 1893, an imported laboratory heater set fire to the Trudeau family’s house while they were away and burned it to the ground. “There is nothing like fire to make a man do the Phoenix trick,” consoled Dr. William Osler.

The Saranac Laboratory interior, 2010

The Saranac Laboratory interior, 2010

The day after the fire, George C. Cooper visited Trudeau, his doctor and his friend, to offer him “a good stone and steel laboratory, one that will never burn up. Plan it just as you want it, complete, and I will be glad to pay for it and give it to you personally.” The name “Saranac Laboratory” was a compromise between Cooper and Trudeau, who each wanted to name it after the other.

Architecture

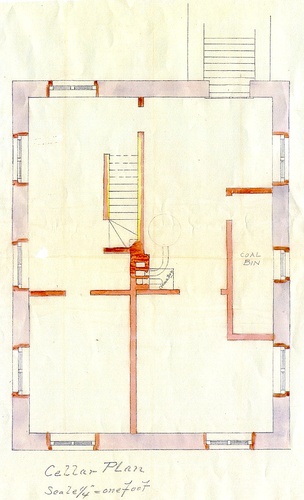

The new, state-of-the-art laboratory was designed for Dr. Trudeau by his cousin, J. Lawrence Aspinwall, junior partner of James Renwick in the New York City firm of Renwick, Aspinwall & Renwick. Branch and Callanan Lumber Company of Saranac Lake built the laboratory between May and November of 1894, at a cost of $20,000, fully equipped. Dr. Trudeau provided land, “part of my house lot on Church Street … convenient for Dr. Baldwin and for me."

The Saranac Laboratory was the first laboratory in the United States built exclusively for research on tuberculosis. Trudeau and Aspinwall planned this laboratory with particular attention to fire protection, light, ventilation and disinfection.

“We had no opening ceremonies and never have had any,” wrote Trudeau. “When everything was ready, Baldwin and I merely began to move the apparatus we already had in use from the little shed near the barn to our beautiful new quarters, and to continue the work we were doing.”

To replace the Queen Anne-style house that had burned, Aspinwall also planned a new Colonial Revival home and office for Trudeau, in use to the present day as the offices of Medical Associates, successor to Dr. Trudeau’s practice.

The Saranac Laboratory interior, 2010

The Saranac Laboratory interior, 2010

In 1903, Elizabeth Milbank Anderson of New York City assumed the full operating cost of the laboratory. 1

From the very beginning of his laboratory studies Trudeau had used animal subjects, perhaps more readily than his urban counterparts because he was a hunter and they were more easily available in the country. Facilities for animals were a part of the original design of the laboratory. Declared Trudeau, “A hundred or more of these animals (rabbits, fowl, and guinea pigs) are kept in cages in the basement. They have good care and never suffer either from the disease or in the manner of their death.” In 1910, Trudeau wrote in the Journal of the American Medical Association: “Thanks to animal experimentation, we know today that tuberculosis is not inherited; that it is communicable and, therefore, preventable; and that in its earlier stages it is curable.”

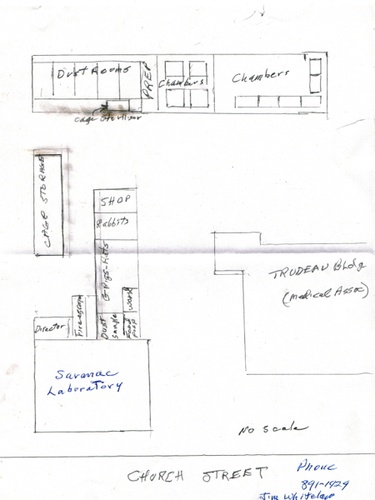

In 1926 an addition was made at the rear of the building to provide more space for raising experimental animals. It was torn down around 1970, but the concrete floor can still be seen.

The left wing addition—the John Black Room and upstairs offices—was completed in 1934.

The Saranac Laboratory closed in 1964, with the on-going experiments transferred to the new Trudeau Institute, where Dr. E.L. Trudeau’s influence in science continues today.

The laboratory building was donated to Paul Smith's College in 1966; it served as classroom and dormitory space until the college’s new building opened next door in 1987.

Restoration

Historic Saranac Lake became the owner of the former Saranac Laboratory in 1998, and has since worked to restore the building as a museum and history center dedicated to interpreting Saranac Lake’s unique role as a pioneer health resort for research and treatment of tuberculosis.

Tony Delahant, right, at work in with fellow laboratory technician, Robert Liddy, on left, after 1934. Photo courtesy of Kay and Marvin Best.

Tony Delahant, right, at work in with fellow laboratory technician, Robert Liddy, on left, after 1934. Photo courtesy of Kay and Marvin Best.

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, September 9, 1952

World-Famed Health Experts To Attend Saranac Symposium

The Seventh Saranac Symposium, opening here September 22, will attract to Saranac Lake approximately 200 world-famed medical and industrial experts for discussions of health problems pertaining to workers exposed by inhalation to industrial substances.

The Saranac Laboratory will be the host. The Symposium is by far the biggest ever to be held here since they were begun by the late Dr. Leroy U. Gardner.

The health of workers in coal, silica, asbestos, beryllium and bauxite industries will be discussed. A large place in the Symposium will be given to cancer of the lung in workers exposed to various industrial substances. Engineering, medical, legal and social angles of the industries will be explored.

Participants in the program, which will extend through Friday, September 26, will include, in addition to physicians, surgeons and scientists of this area, lung specialists not only from America but Canada, Great Britain, Jamaica, South Africa, Holland, Switzerland and South America.

Registration will be at the John Black Room of the Saranac Laboratory on September 21-22.

Among those who will attend the meetings are Dr. Paul Cartier, medical director of the Thetford Industrial Clinic, Thetford Mines, Quebec; Dr. Charles Fletcher, research director at Llandough Hospital near Penarth, Cardiff, Wales, and senior lecturer of the Postgraduate School of Medicine, University of London; Dr. Fernand Gregoire, medical director of Lavoisier Institute, Montreal; Dr. Philip Hugh-Jones, senior lecturer in medicine of the University of the West Indies, Jamaica; Dr. Anthony J. Lanza, chairman of the Institute of Industrial Medicine New York University; Dr. Edgar Mayer, clinical professor of industrial medicine, New York University Postgraduate Medical School and member of the Board of Chest Consultants, Workmen's Compensation Board of N. Y. State.

Dr. E. R. A. Merewether, senior medical inspector of factories, Ministry of Labour and National Service, London: Dr. A. J. Orenstein chief medical officer of Rand Mines, Johannesburg, South Africa Ivan Sabourin, Queen's Counsel, Counsel to Quebec Asbestos Producers Association, Montreal; Dr. C. G. Shaver, superintendent of Niagara Peninsula Sanatorium, St. Catherines, Ontario; and Dr. Donald Solandt, professor of physiology and of physiological hygiene, Faculty of Medicine, Toronto.

Among the Saranac Lake lecturers will be Dr. Philip C. Pratt, Dr. George W. Wright and Dr. Leonard J. Bristol, Edward Urban and Thomas Durkan.

The sessions will be opened by an address of welcome by Dr. Arthur J. Vorwald, director of the Saranac Laboratory and the Trudeau Foundation. Then there will be a forum on pneumoconiosis at which Dr. Vorwald will be moderator. The afternoon session on the first day will be devoted to discussions of health protection for workers in silica, asbestos, beryllium and bauxite.

Tuesday, September 23, will be devoted to consideration of the health of coal miners. The subject for the third day will be "Pneumoconiosis and Pulmonary Cancer" Thursday morning there will be lectures and discussions on the clinical aspects of pneumoconiosis.

Thursday afternoon the medical and legal aspects of workmen' compensation will be considered. That night there will be a banquet at the Hotel Saranac at which Dr. Francis B. Trudeau will make few remarks and Dr. Anthony J. Lanza will deliver the Leroy U. Gardner memorial lecture.

The topic for Friday's session will be compensation for pulmonary and other occupational diseases. The symposium will conclude Friday afternoon with a summary of the sessions by Dr. Vorwald.

Floor plans for the Saranac Laboratory, first floor, c. 1894. Courtesy of the Adirondack Research Room, Saranac Lake Free Library

Floor plans for the Saranac Laboratory, first floor, c. 1894. Courtesy of the Adirondack Research Room, Saranac Lake Free Library  Floor plans for the Saranac Laboratory, basement, c. 1894. Courtesy of the Adirondack Research Room, Saranac Lake Free Library

Floor plans for the Saranac Laboratory, basement, c. 1894. Courtesy of the Adirondack Research Room, Saranac Lake Free Library  Map of the back of the laboratory, c. 1950s-60s, provided by Jim Whitelaw, 2013 Adirondack Daily Enterprise, August 25, 1988

Map of the back of the laboratory, c. 1950s-60s, provided by Jim Whitelaw, 2013 Adirondack Daily Enterprise, August 25, 1988

'Saranac Lab' restoration in the works

By CHRIS MELE

SARANAC LAKE — Architect Carl Stearns believes the 94-year-old Trudeau Laboratory on Church Street is a lot like a Model A Ford — with a little tinkering and a tune-up it can be as good as new.

Stearns is acting the part of the mechanic, planning what repairs are needed to restore the building and retain its historic qualities.

"It's like a Model A. When you first see it, 'Who wants it?' is the first response," Stearns said. "There's no limit to how many times you can rebuild a Model A Ford."

With the help of a $1,000 matching grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Paul Smith's College and Historic Saranac Lake hired Stearns to assess the "Saranac Laboratory," the first in the United States to be built for the study of tuberculosis.

Stearns reported his findings this week in a slide show presentation at the Hotel Saranac to a gathering of college officials and historians.

The brick and mortar building is structurally sound, but it needs some cosmetic repairs he said. In one front corner the bricks have been badly worn by years of water running down from the pitched roof.

The mortar in some places is eroded as deep as five inches, Stearns said, showing a slide where a quarter fit into the gap between two bricks.

The front stone steps should be dismantled and put back together. Other repairs include fixing pinholes in the roof, rewiring the building's electrical system and constructing a ramp along the side to make it accessible to the handicapped.

Stearns estimated it would cost $180,000 to bring the building up to the modern building code. His report will be turned over to a college committee studying the future use of the 6,000 sq. ft. building. Consideration is being given to using it for classroom and meeting space.

Built in 1894, the laboratory was constructed to the specifications of Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, a pioneer scientist in TB research. Trudeau Himself was stricken with "consumption" and came here expecting to live out the last months of his life. Unpredictably, he survived and spent many years devoted to caring for other TB victims.

The first lab at 7 Church St. was destroyed by fire. Within hours, a friend and patient, George C. Cooper, had offered to build "a good stone and steel laboratory, one that will never burn up." Trudeau described the building in these words: "The building is a most substantial and dignified structure. As nothing but cut stone, glazed brick, slate, steel and cement entered its composition, it is absolutely fire-proof. The inside is all finished in white, glazed brick, and it looks absolutely indestructible — as if it were not built for time, but for eternity!"

In his inventory of the building, Stearns found many noteworthy architectural touches. There are brick arches over the windows (which required skillful masonry work), large gabled windows (some of which have been lost), cloverleaf ventilation grates, winding stairways and the use of two-color brick construction in a Colonial Revival style.

The interior is a maze of rooms and stairs. The John Baxter Black Memorial Room, a one-story addition built on the south side of the lab in 1928, featured a huge library and lecture hall. In 1934, a second floor was built onto the memorial wing. A large addition behind the lab that housed laboratory animals was demolished about 15-20 years ago, according to Stearns.

The attic of the lab doubled as storage space and a place where experiments took place. In later years, doctors at the lab researched the effects of industrial dusts, like those associated with granite quarries and the steel, cement and gypsum industries. Some of the earliest labor safety laws were an outgrowth of this research.

The building was donated to Paul Smith's College in 1966 and served as a classroom and dormitory space for 12 years. Since January, when a new dormitory was opened next door, the lab has remained locked and empty — awaiting new occupants.

Adirondack Daily Enterprise, February 23, 2002

Historical building to make history once again

By ANDY FLYNN

Special to the Enterprise

SARANAC LAKE - The preservation group, Historic Saranac Lake, is quietly making history this Week as renovations inside the Saranac Laboratory begin.

Constructed in 1894, the Saranac Laboratory on Church Street is one of the most important historical structures in Saranac Lake, yet hundreds of the people who drive by it every day are unaware of the significant role it played in the history of science. It was the first research laboratory in the United States for tuberculosis and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

"It was built right at the dawn of science," said Mary Hotaling, director of Historic Saranac Lake.

Hotaling is orchestrating the Saranac Laboratory restoration, which is a multi-faceted project that will include renovating, reconstructing, adapting to handicapped accessibility issues and making it a practical work space while preserving aspects of historical integrity. The building was constructed in three phases: the main laboratory in 1894, a first floor addition in 1928 and a second floor to the addition in 1935.

"It's restoration, and it's also putting in an adaptive use for the building," Hotaling said. "We have to have a modern day viable use for it."

Historic Saranac Lake's modern-day use for the Saranac Laboratory includes the rental of office space. Kisco Systems, a computer company based in the New York City suburb of Mount Kisco, will be relocating to a three-room office on the second floor of the building as of April 1.

Hotaling knew that the Saranac Laboratory renovations needed to start at some point, but a rigid timeline hadn't been set until Kisco Systems owner Rich Loeber said be wanted to move into the building this spring. So she decided to take the plunge and begin the renovations sooner than expected.

Historic Saranac Lake will soon start receiving rental income — money that can be used for renovations to the rest of the building. Inside the original first floor laboratory space, Hotaling said she is going to move Historic Saranac Lake's office into the first room on the left as you walk in the door. Once the group's presence is established, it will be easier to begin work on the rest of the structure, which will feature a museum on the history of tuberculosis in Saranac Lake, she said.

Only three of the five rooms on the second floor will be refurbished for the new computer company, which will require a CAT-5 line (four phone lines in one wire).

"It was built as high-tech, and we want to continue as high-tech," Hotaling said.

With two extra rooms on the second floor, there is space for more tenants. The offices, however, are not specifically designated for a technology-based company.

Looking at the Saranac Laboratory today, it's hard to tell that work is going on inside. Snow blocks the boarded-up front-door entrance, where the door has been removed for renovations. There is no electricity and no heat. Ice has formed inside the cellar entrance where snowmelt has trickled in. But that's where you'll find workers such as Ron King of ROK Electric, putting in the latest technological wiring for the new computer company. Metal studs, to meet contemporary fire codes, have been erected for a new bathroom wall, and sheetrock will cover a 1986 wall mural of a beer mug proudly recalling the days when this was a Paul, Smith's College dormitory — Trudeau House.

Once again, life is beginning to stir inside the Saranac Laboratory.

Brief History of the Saranac Laboratory

The growth of the tuberculosis curing industry in America began in Saranac Lake thanks to Dr. Edward Livingston (E.L.) Trudeau, who opened the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium in 1884. His methods of TB treatment attracted thousands of patients and led to an economic boom in the town. In 1892, the village of Saranac Lake was incorporated, and Trudeau was its first president of the Board of Trustees.

In November 1893, a fire destroyed Trudeau's house and attached lab on the corner of Main and Church streets. It is believed that a burner in the lab was the cause of the blaze. Another house for Trudeau and his family was built on the site, which is now the home of Medical Associates.

After Trudeau's house and lab were destroyed, a philanthropic patient, George C. Cooper, told the doctor that he would pay for a new building for his experiments. As cited from Trudeau's autobiography, Cooper said, "I want you to begin to plan a good stone and steel laboratory; one that will never burn up. Plan it just as you want it, complete, and I will be glad to pay for it and give it to you personally."

Saranac Lake builders Branch and Callanan finished the Saranac Laboratory in November 1894 at a cost of $20,000, according to Hotaling.

In a Dec. 13, 1894 press report, the Essex County Republican described the lab as "entirely fire proof, built of native stone, a grayish trap rock, and lined inside with white enamel brick. The floors are also fireproof being built of iron and brick. The building is 40 x 30 and has one story and basement. The upper floor is divided into a library, main laboratory, Dr. Trudeau's private laboratory, attendance room and an autopsy room. The basement is devoted to animal rooms and hot water heating apparatus."

The building was to be lighted with electricity and included two large incubators in which the bacilli of tuberculosis were developed, powerful microscopes, sterilizers and all the instruments needed for bacterial examinations.

Water was run through stone filters. Fresh air was circulated through the building to prevent the researchers from getting infected by the tuberculosis experiments.

"The quality of construction is so wonderful, so different, "Hotaling said, adding that it's a stark contrast to buildings of that day because most of Saranac Lake in 1894 consisted of wooden structures. "This was state-of-the- art when it was built."

The Saranac Laboratory on Church Street is one of the most historically significant structures in Saranac Lake.

Trudeau described the new building's interior in his autobiography. "The inside is all finished in white, glazed brick, and it looks absolutely indestructible — as if it were built not for time but for eternity!" said Trudeau after the Saranac Laboratory was complete.

The white brick, which still gives the interior its laboratory-style character, reflected the abundance of light coming in from the building's 10 giant two-over- two sash windows, sized at about 4.5 feet by 9.5 feet. The enamel brick was also easily disinfected.

The Saranac Laboratory was used chiefly for basic scientific research in the field of tuberculosis and other lung diseases. Clinical experiments were conducted at the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium, which was located on the side of Mount Pisgah (where the American Management Association offices are today).

In 1928, the family of former TB patient John Black donated the money to build a scientific research library wing onto the Saranac Laboratory. The John Black Memorial Library, a one story structure, featured the latest medical books and was used as the headquarters for the Trudeau School of Tuberculosis. In 1935, a second floor was added for office space. Again, John Black's family donated the second addition in his memory.

The Saranac Laboratory is the predecessor of the, current Trudeau Institute, which was founded in 1964 by Dr. Trudeau's grandson, Dr. Francis B. Trudeau, Jr. Due to the effectiveness of drug treatments, the Trudeau Sanatorium, was no longer needed, and closed in 1954. The Sanatorium's president, Dr. Francis B. Trudeau, Sr. (E.L. Trudeau's son) handed over the closure to his son, who secured the sale of the property to the AMA in 1956.

With the opening of the Trudeau Institute, the Saranac Laboratory was no longer needed. The basic scientific, research originating, from the Church Street building, was to be conducted at a grander facility on the shore of Lower Saranac Lake. Located on Algonquin Avenue the Trudeau. Institute property today features a life-sized sculpture of Trudeau and his first original cure cottage — Little Red. The Trudeau Institute recently expanded with a new addition of its own.

Subsequently, in 1966 the Saranac Laboratory was donated to Paul Smith's College, which owns and operates the nearby Hotel Saranac. By 1974, the college had renovated the building for classroom and dormitory space. It was renamed the Trudeau House, but by January 1988, a new dorm had been constructed next door, and the Trudeau House was locked up and abandoned.

In 1999, an anonymous donor gave the Saranac Laboratory to Historic Saranac Lake for preservation purposes.

A new beginning

The Saranac Laboratory project conjures up excitement in Hotaling, who never knows what she will find next at this historic site.

It's a very complex building. It's hard to figure out when you are here," Hotaling said. "I'm always being surprised."

One surprise came when Hotaling found one of the giant windows and sashes inside the bathroom of the main laboratory, where shower stall drains are still evident from its college days. The window, which was adjacent to the John Black Library Wing, was boarded up when the addition was built. When the Trudeau House paneling was removed from the enamel bricks, the original window was found and then moved to one of the other window spaces, where it will be featured in the future museum.

"I didn't know that there would be an old window in there," Hotaling said. "We were glad to find the whole sash."

At every turn, every glance, there seems to be a fascinating aspect of historical significance at the Saranac Laboratory. Looking at the ceiling, for instance, where iron beams separate white-painted brick arches, Hotaling said, "The building is built like the (19th century) New York subways."'

Over the past 108 years, many architectural changes have been made to the Saranac Laboratory — additions, renovations — and it has been used by hundreds of different people over that span of time — from ground-breaking American scientists to keg-tapping college freshmen.

Yes, time has taken its toll on the Saranac Laboratory. Just getting the college dormitory's paneling glue off the white, enamel tiles will present its own challenges. With many more surprises to come, it is just the beginning of a new venture for Historic Saranac Lake. This time, however, it will be the preservation group making history.

Saranac Laboratory from the west, 2010

Saranac Laboratory from the west, 2010

Workers (other than directors) at Saranac Laboratory, 1894-1964

Albert H. Allen; Gordon Snyder, M.D. 2; John Schmidt; Donald E. Cummings, chemical engineer; Edward L. Gockeler, photographer; Jean Mason, student intern 1964; Bill McKentley; Peggy Campion, student intern, 1964; Garry Trudeau, student intern, 1964; Ollie Duprey, student intern 1964; Lillian Blinn; Eileen Fanning; Phoebus Levene; Victor Hugo; Malcolm Roberts; Anthony J. Lanza; Robert Liddy; Leonard Bristol; D. S. McCrum; Anthony Brady Delahant; Jim Whitelaw; Ruth Grossman

See also: E. L. Trudeau Letter and http://www.mesothelioma.co/asbestos/asbestos-industry-cover-up/altered-medical-research.aspx

Directors of the Saranac Laboratory

Dr. E. L. Trudeau, 1885- 1900?

Dr. E. R. Baldwin, 1900? - 1926

Dr. LeRoy U. Gardner, 1926 - 1946

Dr. Arthur J. Vorwald, 1946 - 1953

Dr. G. W. H. Schepers, April 1953 - at least 1958

Dr. George W. Wright, 1959 - Nov. 1960

The corporate status of Saranac Lab was dissolved and merged with the Trudeau Foundation.

From "History of the Saranac Laboratory, 1885-1959," by Lillian Blinn (1959)

Essex County Republican, May 3, 1894

--The contract for the masonry of Dr. Trudeau's new laboratory at Saranac Lake has been awarded to Branch & Callanan of Saranac Lake, for $20,000.

Footnotes

1. An Autobiography, by Edward Livingston Trudeau, p. 267

2. annals.org/cgi/contents.