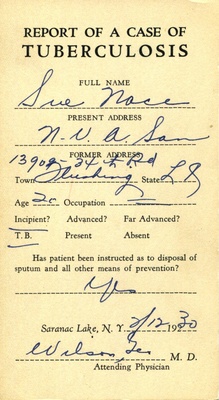

One of the records kept by the Board of Health The Saranac Lake Board of Health was created in 1896. In 1908, they published a Health Code that won the silver medal of the Tuberculosis Congress. 1

One of the records kept by the Board of Health The Saranac Lake Board of Health was created in 1896. In 1908, they published a Health Code that won the silver medal of the Tuberculosis Congress. 1

Dr. Ezra S. McClellan served as president in its early years; Dr. E. R. Baldwin was president from 1899 to 1901; Dr. Bradley Sageman served as president in the 1950s.

"Experience discloses the fact that commendatory appreciation of the endeavors of individuals to conform with sanitary requirements, which often are irksome and apparently unnecessary and detailed explanation of the necessity for fulfilling the requirements of the Health ordinances, will accomplish more than pages of threatening invective or even judicial writs of coercion."

— Bulletin Saranac Lake Board of Health Vol. i No. 6. Quoted in the The Ohio public health journal of the Ohio State board of health, 1917, Volume 8, p. 211. link

Plattsburgh Sentinel, September 16, 1892

SARANAC LAKE.

—At a special meeting held on Monday to consider the questions of water-works and sewage for the village, it was decided with but five dissenting votes, to bond the town for thirty thousand dollars for water-works, and seven thousand for sewers.

The World's Work, Vol.24, May to October, 1912, Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Co.

SANITARY SARANAC LAKE

A SMALL TOWN THAT HAS HAD ONLY SEVENTEEN DEATHS FROM CONTAGIOUS DISEASES IN TWELVE YEARS —

A MODEL WATER SUPPLY, SEWERAGE SYSTEM, AND A REMARKABLE HEALTH CODE THAT IS ENFORCED

BY

(The World's Work announced, in May last, a prize of $100 to be awarded for the best article on the sanitary regeneration of a small town. The editors chose the following article, from the many excellent manuscripts that were submitted, as being the most sug~ gestive to other small communities that confront the problem of improving their health conditions.)

A COMMERCIAL traveler came out of the dining room of a Saranac Lake hotel last winter and casually expectorated over the verandah railing. A plain man in plain clothes walked up to him, announced himself as a health officer, and placed the drummer under arrest.

"But — Good Lord!" exploded the commercial stranger. "This is beyond the limit."

"Spitting in public places is a misdemeanor," said the health man, unemotionally.

"But — Great Ginger!" exclaimed the drummer. There was little more that he could say, for he knew of the existence of similar ordinances elsewhere, but elsewhere they were mostly honored in the breach.

"But not here," said the health officer, as he led his prisoner toward the office of a justice of the peace. "We had an anti-spitting ordinance in this town before ever the State Board of Health or New York City passed one. We are beating them to it in the enforcement, likewise."

"Well, what's a man to do?" the drummer demanded, furiously.

"There are cuspidors at the hotels," said the officer. "Outside, if you must expectorate, use one of these," — handing the prisoner a patent paper pocket cuspidor such as you can buy at any drug store for about a dollar a gross. "And burn the old one before you use a fresh one," added the health officer.

As the drummer was a stranger and did not know his Saranac Lake, the judge discharged him with a reprimand. The first act of the commercial traveler when he regained the street and liberty, was to expectorate once more — this time, let us say, in an excess of agitation. Again a hand fell on his shoulder, and again he was led before the justice.

"So soon again?" said the judge. "Ten dollars!"

As the drummer paid the fine he asked the health officer with much sarcasm if this was the spotless town he had heard of where they scrubbed the streets every morning with patent soap.

"No," said the Board of Health man, smiling. "We just hose the ignorant with common sense and let it go at that."

But Saranac Lake, a pretty little town in the Adirondacks with a population of 5,000, is as deserving of the title, "spotless town," as any place of any size in the United States. Notwithstanding that young inhabitants can remember when there was no railroad connection between it and the world, it has been a pioneer in the practice of a scientific sanitary code. Saranac Lake's code has wielded a widespread influence and its example was not lost upon New York City and upon the New York State Board of Health when the latter came to make its general code. Furthermore, in 1908 a national congress of eminent physicians, assembled at Washington, saw fit to award Saranac Lake a medal for the excellent preventive and curative health ordinances which govern that rural community.

Briefly, here is a town of at present 5,000 resident inhabitants, where, since the health ordinances were put into force in 1896-7 —

1. There have been no deaths from measles or scarlet fever;

2. There have been but 2 deaths from diphtheria, one being of a child brought into the town in an advanced stage of the disease;

3. Typhoid fever has claimed only 10 in fifteen years, 6 deaths occurring in the first four years of the Health Board's existence, and the remaining 4 in the ensuing ten years, when the population had more than doubled;

4. Tuberculosis claimed, during the first four years of the Health Board's, existence, from 1897 to 1900 inclusive, one person in 693; from 1901 to 1905 inclusive, one person in 1,241; and from 1906 to 1911 inclusive, one person in 3,125.

The figures on tuberculosis are for the resident population, which has increased during the Board's existence from about 1,500 to 5,000. In fairness to the town I exclude from death statistics a floating population of about 1,000 persons going and coming to and from all parts of the United States in search of a tuberculosis cure. The present average annual death rate from all causes for the total number of persons in the town is about 150 annually. Comparing this with the figures for the resident population, one will at once perceive where the greater number of deaths from all causes comes from. As a great many victims of tuberculosis go to Saranac Lake as a last hope, and already in a dying condition, it would be unfair to the town to consider such deaths as any criterion of the place's general health.

Twenty years ago Saranac Lake was a backwoods hamlet with a population of less than 1,000, cut off from the world by forty miles of wilderness, drawing its water in buckets and barrels, emptying its sewerage and garbage at the back door, more or less ridden with typhoid, diphtheria, and other communicable diseases. To-day —

1. It has a sewerage and water supply system which is far ahead of that in any other town of its size;

2. Its streets are paved and the town is lighted throughout by electricity;

3. It has a street-cleaning department, a fire department, an efficient police force, and a body of general inspectors of town conditions;

4. Its merchants and physicians are organized in a Board of Health, a Board of Trade, and a Society for the Prevention and Control of Tuberculosis;

5. Its matrons are organized in a Village Improvement Society for the general uplift of the town and directly for the encouragement of the sanitary household;

6. And it is a town where the percentage of deaths among resident inhabitants, from contagious diseases contracted within the town limits, is a minimum difficult of figuring because several years may elapse without a single death occurring under this head or that.

This last item is the more astonishing when it is considered that a large proportion of the resident population went to the town with tuberculosis, was cured of it, liked the place, and settled there.

The proof of Saranac's claim is that, although there are never less than 1,000 cases of tuberculosis in or around the town (transient patients), there is no case on record of any resident contracting the disease through proximity. The health measures in this rural town are such that any germ of any disease is at least corralled in the person who has it. Saranac Lake has established beyond argument that Hester Street or Hell's Kitchen could be as immune as this mountain town, if either were similarly regulated. The motto of the municipal crusaders against communicable diseases might well be:

"Take care of the garbage and the air will take care of itself."

Everybody who has read the letters written by Robert Louis Stevenson from Saranac Lake in 1887-8 must have a fairly clear idea of what conditions were then.

AS STEVENSON KNEW THE TOWN

It was a scattering of shacks along the banks of the Saranac River, which was at once the main sewer, the main water supply, and the family washtub. Typhoid vied with diphtheria to head the death statistics (if they were ever kept!). The winter air and the night air were dreaded, for those were the dark ages. There was tuberculosis then among the resident population, for it was cold and the houses were kept almost hermetically sealed. The living room was practically the woodyard in winter. Fuel was the principal furniture, for the stoves were voracious. Stevenson was not the only man in Saranac who locked himself up with wood smoke and tobacco reek and turned a deaf ear to that exponent of the efficacy of fresh air, Dr. Trudeau.

The garbage was heaved out at the backdoor (and the door shut — quick!); the water was thawed from blocks of ice of a morning, and there was usually a sediment of mixed matter at the bottom of the family drinking pitcher; and when the spring thaw bared the scrap heap of winter, there came an aroma — no, a plain smell! — upon the land, and much sickness descended upon the people.

In the warm summer months matters were worse — naturally. The only thing that preserved the Saranackers was that they were an outdoor people, of necessity — men of the woods, mighty hunters — and they waxed healthy enough in summer and fall to face winter's insanitary conditions with a minimum of deaths from diphtheria and typhoid and tuberculosis.

Then came the railroad extension to Saranac Lake in 1888. With the coming of the first train there awakened the native instinct of a shrewd people. At the approach of strangers, Mrs. Saranac rolled up her sleeves and bought a cake of soap. She scrubbed the village from top to bottom (it is built mostly on end), aired the rooms and made a flower garden, while her husband, Silas, put the pig-sty well to leeward, gathered all the information he could get about city ideas and city ways, and prepared to meet the city people for the honor of the family and the village.

But if the city people in 1888 had more ideas about sanitation than Silas Saranac had, a great many of them were wrong. It was not long before Saranac Lake took advantage of every city idea of sanitation that struck the village wiseheads as being good. At the same time, and at the advice of Dr. Trudeau, Saranac Lake tabled some accepted ideas of sanitation which, it decided, belonged to the dark ages.

BUILDING HOUSES INSIDE OUT

Then a town began to build — suddenly, it is true, but very carefully. Most of the city people who came to the hills seemed to thrive on the fresh air (it could hardly be on the food, which was distinctly inferior); so between one day and the next shrewd Silas Saranac came to the conclusion that he had been fooling himself all along about the deadliness of air. He acted upon this conclusion and built his new house inside out. To-day the Saranac Lake houses are all inside out, and they will become more so as time and architecture roll on.

Up to 1892, however, nothing really effective was done toward those excellent sanitary measures which were destined to win the medal of a great congress of health experts. Then the man came to the mountain hamlet who was needed to make it what it is— Dr. Ezra S. McClellan, of Georgetown, O.

One year after his arrival the first public water supply was turned on. It came from a reservoir on one of the hills, the water being pumped by a turbine direct from the river. Less than twelve months later, a small sewer was laid. This was between 1892 and 1894.

In later years, when the rapid growth of the community necessitated re-improvement, and on a larger scale, Dr. McClellan, who in the meantime had become a member of an organized Board of Health, was appointed president of a Board of Sewer and Water Commissioners. It was McClellan's enthusiasm more than anything, perhaps — and it shows what one man can do in a community — that led to the installation of Saranac Lake's present excellent water and sewer system. The system itself was planned, I believe, by Professor Olin H. Landreth, of Union College, Schenectady.

About this time the supply dam broke and the water supply was badly polluted as a result. Dr. McClellan started legislation to have the dam rebuilt. A measure was introduced at Albany toward this end. On the day before the signing of bills, Dr. McClellan received private information by wire that Governor Black meant to veto the proposition. The valiant doctor jumped on a train and reached Albany and the Governor at the eleventh hour and fifty-ninth second.

"Governor Black," said he, "years ago the state of New York built a dam in the Saranac River six miles above our village. That dam is now dilapidated, The water is frightful. Existing conditions are such that a terrible epidemic of typhoid threatens us. The village of Saranac Lake holds the state of New York responsible!"

It was a terrible responsibility. Governor Black signed the bill and the dam was rebuilt.

Still the Board of Health of Saranac Lake was not satisfied. Again it was Dr. McClellan who questioned the perfectness of the water supply. After lengthy argument the village found itself in a position to advertise its drinking-fluid as the real honey-dew -- the milk of paradise. The town purchased and deeded to the state an isolated little lake at the base of Mount McKenzie. This natural reservoir, fed by numerous mountain brooks, is surrounded by state forests. Bathing, fishing, even boating, are forbidden there. The water is liquid crystal and it is protected by the state for all time.

Incidentally, having now a fine water pressure, another village board organized a fire department and a street-cleaning department, and bought a sprinkler to lay dust. It is really remarkable what a lot of things can be done with plain water — and soap — and a little ginger!

To go back to the real beginning, it was in July, 1896, that Saranac Lake organized its Board of Health. The best of the town's level heads came together at its meetings. One of the first measures passed was the anti-spitting ordinance. This was in December, 1896. Thus, New York City was "beaten to it," as the health officer said to the drummer, by several months.

It is characteristic of the admirable solemnity of a country board that this anti-spitting ordinance was not passed for fun, or to satisfy any faction of the ultrafastidious. "Good sanitation as well as good manners" required it, said Silas Saranac. The man of the street and the hotel verandah who punctuates a yarn with deadly expectorate periods, laughed at the ordinance until he found himself haled before a judge. Nowadays, an arrest for reckless punctuation is rare in Saranac Lake. To some, the cost appeals strongly: to most, the ordinance is too blessed to be violated.

Next, the Board of Health used diphtheria anti-toxin for the first time in Franklin County, and found it good. Then came compulsory disinfection (by the use of formaldehyde) of all rooms in hotels and boarding-houses vacated by persons even suspected of having a communicable disease; and the requirement that hotel and boarding house keepers not only disinfect vacated rooms, hut also foot the bill! The Board realized that greater numbers were coming every year to Saranac Lake in search of a cure for tuberculosis, and that it would be a terrible burden upon the taxpayers to pay the cost of the fumigations incidental to a transient population of 1,000, more or less all the time. And so, in most cases, the "extra" creeps into the guests' bills, which is fair enough. In protecting others against him, he is being protected against others. This provision of the ordinance is probably unique in either codes.'

A PRIZE-WINNING HEALTH CODE.

It was not until 1908 that the work which the Saranac Lake Board of Health had done since its organization in 1896 was published as a completed sanitary code. It was this code which, in the same year, won for the town the silver medal of the Tuberculosis Congress. New York City, I think, took the first prize. This code covers everything imaginable that might touch good health. It even forbids keeping a profane parrot, and, abolishing pigs altogether, declares that in Saranac Lake one must not keep chickens. The latter ordinance, to round out perfection with a flaw, is studiously winked at!

In 1908-9 Saranac Lake put the finishing touches to its town by paving the two business thoroughfares and the main residential street, and at the present moment the paving of the whole town is under consideration. Reeking lamps were abolished years ago. All lighting is now by electricity.

Before Dr. McClellan died he heard men speak of that metamorphosed backwoods hamlet as "the metropolis of the Adirondacks," paved, electric-lighted, modern yet rurally charming, and with an impregnable sanitary code. He could well say, "only seventeen deaths in twelve years from any contagious diseases, including typhoid" — and die happy!

The remarkable thing about Saranac Lake's ordinances is that they mean business until' repealed. The town is absolutely in accord about its health ordinances. There are few complaints and few violations. The former are attended to with a promptness, and the latter with a severity, that inspires not so much fear as confidence and respect. But the housekeepers of Saranac Lake are proud of their town and its sanitation, The women are the directors of the Village Improvement Society, which is the censor of every other board or society in town. To the influence of this gentle board of energetic women is due, perhaps, the absence of disorderly saloons, gilded palaces, and the resulting social evil. Few communities of even less than 5,000 inhabitants can truthfully say that there is not a single house of evil repute within miles of its limits.

Then, too, this society of women sets an example and takes a stern interest in garbage disposal, the acquiring and beautifying of parks and playgrounds, and expresses itself (when it becomes necessary) upon matters of street-cleaning, social organizations, the public library, or upon any other subject which it fancies the busy men have overlooked.

After all, health and progress in any community depend upon the proper conduct of the individual household. As woman is, or should be, supreme in the home, it would seem that, after the men have laid the sewer and turned on the water, the rest depends greatly upon the wife and her perception of the real opportunities under her nose.

Mrs. Silas Saranac saw hers and bought a cake of soap. To-day she is, as the Scotch would say, "the proud woman!"

___

Footnotes

1. The World's Work, Volume XXIV, May to October, 1912, A History of our Time, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1912, pp. 584-585. link