Liverpool's Destroyed or Demolished Landmarks

| It’s difficult not to conclude that, in its relentless post-war economic decline, Liverpool became consumed by a hatred of its own past - Dr Gavin Stamp 2007 |

Customs House

Custom House from Castle Street

Custom House from Castle Street  Custom House Basement Exposed after Demolition Viewed from South Castle Street, which is now the site of the Liverpool One development, Sewills the watch, clock and chronometer makers is near the end of the row of shops on the left; the sign can be seen in the photographs. The firm still exists, having moved to Knowsley, but now only repair instruments not manufacturing. Sewills, established in 1800 are the oldest timepiece company in the world.

Custom House Basement Exposed after Demolition Viewed from South Castle Street, which is now the site of the Liverpool One development, Sewills the watch, clock and chronometer makers is near the end of the row of shops on the left; the sign can be seen in the photographs. The firm still exists, having moved to Knowsley, but now only repair instruments not manufacturing. Sewills, established in 1800 are the oldest timepiece company in the world.

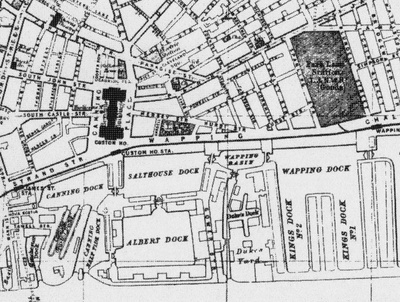

The loss of the Custom House was almost certainly Liverpool's greatest architectural casualty of the Second World War. This huge domed building with large grand porticos graced the south end of South Castle Street with its dome complementing the dome of the Town Hall at the opposite end of Castle Street. In plan area, the building was larger than St Georges Hall and, like the hall, built in the classical style. The Liverpool One shopping mall now stands on the site of this former landmark.

The Custom House was built between 1828 and 1839 by city architect John Foster on the site of the original Old Dock. It housed a post office, a telegraph office and offices for the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board. During the May Blitz of 1941, the building was heavily damaged by German fire bombs which gutted the interior and destroyed the dome. The decision to demolish the shell of the building after world war two was met with widespread disapproval. There is controversy to this day about the extent of damage to the building and whether or not reconstruction would have been practical. The loss of the Custom House was Liverpool's greatest architectural casualty of the Second World War.

The Goree Warehouses

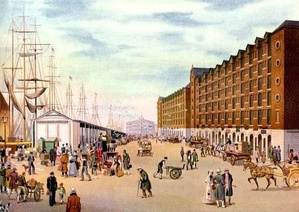

Goree Warehouses in 1850 with George's Dock to the left The Goree Warehouses, built 1793, were named after a slave embarkation island off Senegal, West Africa, which also gave its name to the adjacent road by St Nicholas's Church known as Goree Piazza. There is a folk belief that iron hoops in the walls were used to chain up African slaves but this is untrue. The Warehouses were built 11 years after the courts ruled that every slave became free as soon as his feet touched English soil.

Goree Warehouses in 1850 with George's Dock to the left The Goree Warehouses, built 1793, were named after a slave embarkation island off Senegal, West Africa, which also gave its name to the adjacent road by St Nicholas's Church known as Goree Piazza. There is a folk belief that iron hoops in the walls were used to chain up African slaves but this is untrue. The Warehouses were built 11 years after the courts ruled that every slave became free as soon as his feet touched English soil.

Goree Warehouses Under Demolition with the Three Graces to the left built on George's Dock

Goree Warehouses Under Demolition with the Three Graces to the left built on George's Dock

The warehouses were demolished in 1958 following extensive Second World War bomb damage. Their site is now part of the Strand, which was widened in the Sixties as part of an ambitious scheme for an inner motorway around the city centre. The only part to have been built was from Leeds Street to Parliament Street.

Cases Street

The Original Clayton Square

The Brownlow Hill Workhouse

The Brownlow Hill Workhouse, built in 1771, was one of the largest in Britain and stood on the site bounded by Brownlow Hill and Mount Pleasant where the Metropolitan Cathedral now stands. The building was demolished in the 1930s to make way for the massive cathedral designed by Edwin Lutyens, which would have been the largest in the world. Only a part of the crypt of this cathedral was ever built before the Second World War with post war stagnation making the scheme unviable. The present cathedral, designed by Frederick Gibberd, now occupies the remainder of the site. The four bells of the cathedral, named Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, were originally the bells of the workhouse.

The associated workhouse infirmary occupies a place in literary history being where Robert Tressel, author of 'The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists' died in 1911.

Commutation Row

Commutation Row was an attractive row of shops and pubs. Demolished in the 1980s.

Bibby's Warehouse

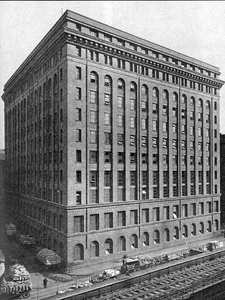

Bibbys Americanesque Warehouse Inspired by the Chicago School of Architecture and designed by W Aubrey Thomas who also designed the Royal Liver Buildings. About two-thirds of his buildings survive. The grain and processing warehouse was considered so important that work on it continued during the Great War with completion in 1917. The building was demolished in the 1980s.

Bibbys Americanesque Warehouse Inspired by the Chicago School of Architecture and designed by W Aubrey Thomas who also designed the Royal Liver Buildings. About two-thirds of his buildings survive. The grain and processing warehouse was considered so important that work on it continued during the Great War with completion in 1917. The building was demolished in the 1980s.

Bibbys Opposite West Waterloo Dock behind Victoria Dock in the fireground. This shows the Bibby warehouse on the left and the two Waterloo Warehouses of which the left (east) warehouse survives and is now luxury flats. Most of the buildings in this picture have been demolished, even the Victoria Dock in the foreground.

Bibbys Opposite West Waterloo Dock behind Victoria Dock in the fireground. This shows the Bibby warehouse on the left and the two Waterloo Warehouses of which the left (east) warehouse survives and is now luxury flats. Most of the buildings in this picture have been demolished, even the Victoria Dock in the foreground.

St. George's Place

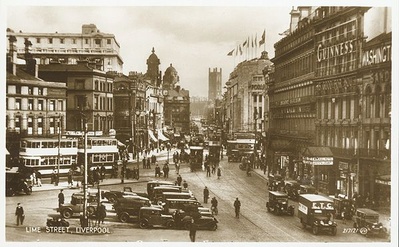

St George's place, (Right), towards The Forum Cinema

St George's place, (Right), towards The Forum Cinema  St.George's place in 1960

St.George's place in 1960

Princes Dock Accumulator Tower

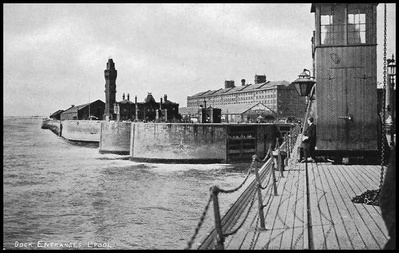

Accumulator Tower at Princes Half-Tide Dock This tall and elegant accumulator tower stood at the north end of Princes Half-Tide Dock, where the docks joins West Waterloo Dock. The tower was demolished after the Second World War to create river locks into West Waterloo Dock. These locks were short lived and are now filled in. The photo is taken from the Princes landing Stage.

Accumulator Tower at Princes Half-Tide Dock This tall and elegant accumulator tower stood at the north end of Princes Half-Tide Dock, where the docks joins West Waterloo Dock. The tower was demolished after the Second World War to create river locks into West Waterloo Dock. These locks were short lived and are now filled in. The photo is taken from the Princes landing Stage.

This tower would have been a wonderful contributor to the Central Docks section of the World Heritage Site.

Duke's Dock Warehouse

Dukes Dock Warehouse 1958

Dukes Dock Warehouse 1958  Dukes Dock Warehouse 1700s

Dukes Dock Warehouse 1700s  The warehouses are seen around Dukes Dock, which is now partially filled in

The warehouses are seen around Dukes Dock, which is now partially filled in

Albert Dock is behind the camera. This Dukes Dock warehouse was demolished in 1964.

The two superb delta portico Brindley warehouses, from the 1700s, were demolished in the 1960s/70s. The double arch allowed for Mersey flat barges to sail into the warehouse to discharge their cargoes. These flats would have sailed on the River Mersey from the Bridgewater canal terminus at Runcorn. Brindley designed the Bridgewater canal including many of its locks and bridges.

A similar fate may have befallen Joseph Hartley's Albert Dock warehouses, which were scheduled for demolition under developer Harry Hyams' 'Aquarius City' proposals. Fortunately, this didn't happen, thanks to the efforts of conservationists such as Quentin Hughes and Tony Moscardini.

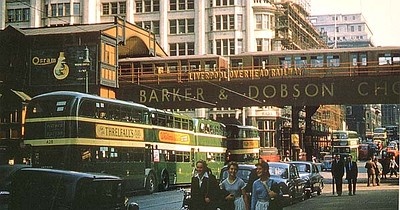

Overhead Railway

Overhead - Pier Head Formation

Overhead - Pier Head Formation

The Liverpool Overhead Railway Company was formed in 1888. The railway was the world's first elevated electric railway. For most of its length it ran above the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board's goods railway forming a dual-level railway.

The railway ran along the whole length of Liverpool Docks and inland at Seaforth to the north terminal station. Ironically for an elevated railway, the southern terminal at Dingle was an underground station.

Construction

As early as 1852 the railway had been suggested, although it was not until much later that the railway came into existence. Engineers Sir Douglas Fox and James Henry Greathead were commissioned to design the railway. They chose electric traction, due to the possibility of sparks from steam trains igniting the cargoes in close proximity to the railway. The works commenced in 1889 and were completed in January 1893.

Opening

The Liverpool Overhead Railway was opened on February 4, 1893, by the Marquis of Salisbury. The railway ran from Alexandra Dock to Herculaneum Dock, a distance of six miles. It used standard gauge track and there were 11 intermediate stations along the line. It was an electric railway from the start, and was the first electrically powered overhead railway in the world.  Nelson Dock from Overhead Railway. 1897 film by Lumiere Brothers

Nelson Dock from Overhead Railway. 1897 film by Lumiere Brothers

Extensions

Liverpool Overhead Railway, Seaforth Sands

The line was extended northwards to Seaforth Sands on 30 April 1894. A further extension southwards from Herculaneum Dock to Dingle was opened on 21 December 1896. Dingle was the line's only underground station and was located on Park Road; the station is now used as a garage. The extension at Herculaneum Dock was achieved with a 200 ft lattice girder bridge and then boring a half mile tunnel through the sandstone cliff to Park Road. The tunnel portal is one of the few surviving signs of the railway's existence.

Finally, a northward extension was connected to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway's North Mersey Branch on 2 July 1905. The Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway ran some of its own specially-built vehicles on the line, and these were especially used during race meetings at Aintree Racecourse.

Modernisation

During World War II, the railway suffered extensively from bomb damage. The owners of the railway successfully resisted incorporation into the rest of the British railway system and was not nationalised in 1948. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the company began to modernise some of the carriages, incorporating sliding doors. The line continued to carry large numbers of passengers, especially dock workers.  Canning Dock from Overhead Railway with Albert Dock Warehouse in the background. 1897 film by Lumiere Brothers

Canning Dock from Overhead Railway with Albert Dock Warehouse in the background. 1897 film by Lumiere Brothers

Decline and closure

The railway was carried mainly on iron viaducts, with a corrugated iron decking, onto which the tracks were laid. As such, it was vulnerable to corrosion. The steam-operated Docks Railway operated beneath most sections of the line with sulphurous smoke from the locos adding to the corrosion problems, however diesel locos were introduced post world war two. During surveys it was discovered that expensive repairs would be necessary to ensure the line's long term survival, at a cost of £2 million. The Liverpool Overhead Railway Company could not afford such costs and looked to both Liverpool City Council and the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board for financial assistance. This was to no avail.

The Liverpool Overhead Railway Company had no option but to go into voluntary liquidation. Despite considerable protest, the line was closed on the evening of 30 December 1956. The final trains each left either end of the line, marking the closure with a loud bang as they passed each other. Both trains were full to capacity with well-wishers and employees of the company.

The service was replaced by a bus service (route number 1) operated by Liverpool Corporation, which could not compete with its predecessor's much faster service, due to congestion along the Dock Road. The public continued to campaign for the railway to reopen, albeit in vain.

Demolition of the structure commenced in September 1957, with the whole structure being dismantled by the following year. The whole viaduct was removed for scrap, leaving very little trace of the railway, save for a small number of upright columns found in the walls at Wapping, the tunnel portal at Herculaneum and the underground station at Dingle. The underground station is now the home of a garage. The station and access tunnel can be incorporated in to Merseyrail metro in the future if predicted passenger levels dictate so.

Film

The railway is featured in the final scenes of the film The Clouded Yellow (1951), as the character played by Jean Simmons uses the railway to travel to one of the docks; extensive archive footage of the railway appears in Of Time and the City, a "cinematic autobiographical poem" made by British film-maker Terence Davies to celebrate Liverpool's 2008 reign as Capital of Culture.

Central Station

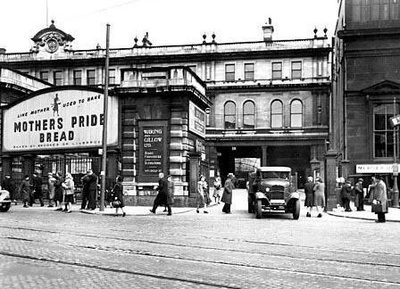

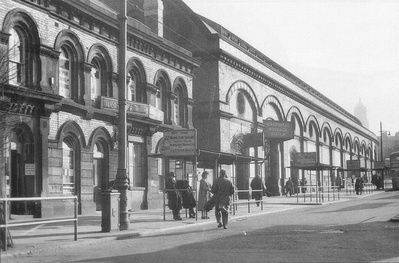

Central Station

Central Station  The frontage changed little over the years

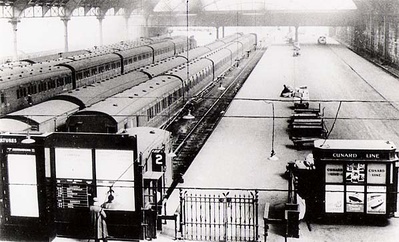

The frontage changed little over the years  The station had 6 platforms

The station had 6 platforms

The original ground level station was opened in 1874, being the Liverpool terminal of the Cheshire Lines Committee line to Manchester Central. The original terminal was on the corner of Sefton Street (Dock Road)/Northumberland Street in the south of the city. The new terminal had an uninspiring three-floor terminal building fronting Ranelagh Street, contrasting with the grand facades of Lime St and Exchange terminal stations. The terminal building was also partially obscured from street level by a single floor building directly in front. To compensate for the uninspiring frontage the station did have an impressive 20 metre high, arched glazed railway shed behind. Trains entered the station via a three track tunnel that ran under south Liverpool. The station had 6 platforms, with services to Manchester Central taking an impressive 45 minutes. In 1892 Liverpool Central Low Level underground terminal station opened, being the terminal of the Mersey Railway from Birkenhead. The underground station is still in use, being converted to a very busy through station.

The station just prior to demolition in 1973

The station just prior to demolition in 1973

The station was busy until the Beeching plans in the early 1960's. Liverpool corporation at the time bucked the Beeching plan and devised linking all the diverse lines constructing a full Merseyside-wide metro. All medium and long distance routes to and from Merseyside would be be run to and from Lime Street Station station with Merseyrail metro servicing Lime Street Station from all Merseyside. This meant closing terminal stations: Liverpool Central High Level, Liverpool Exchange and Birkenhead Woodside station. By 1966, one service remained at Liverpool Central High Level, a local service to Gateacre. This service was withdrawn in 1972 with the large High Level terminal station being completely demolished in 1973. The high level station is now the site of the Liverpool Central Village development.

Original Cavern Club

Mardi Gras Club

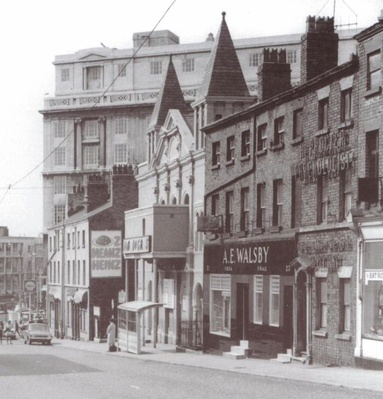

Mardi Gras Club 1966 - Mount Pleasant. The building with the spires.

Mardi Gras Club 1966 - Mount Pleasant. The building with the spires.

The Mardi Gras Club. All the top 1960's Liverpool bands played at the Mardi: The Beatles, The Big Three, Gerry and the Pacemakers, Cilla Black, etc. Originally a church, the building was 225 years old when demolished around 1974/75 to make way for a concrete car park. To the end the Mardi Gras was hosting top bands.

David Lewis Theatre & Hostel

David Lewis Building shortly before demolition

David Lewis Building shortly before demolition  David Lewis Theatre

David Lewis Theatre  Gt George Street - David Lewis Theatre is on the right

Gt George Street - David Lewis Theatre is on the right

The building was erected in 1906 as a hostel, club and theatre, built by philanthropist David Lewis of Lewis's stores. The theatre was was used as a music hall for men using the David Lewis Hostel and Club and the local population. The theatre accommodated around 1000 people. The theatre was first used as a music hall in 1907. Local amateur dramatic societies staged productions to make full use of the theatre. Films were shown from 1914 with sound film projectors installed in 1936. During world war two the theatre was titled the David Lewis Garrison Theatre.

The theatre ceased on 30 November 1977. Demolition of the building was completed in October 1980.

St. John's Church

This church was located directly behind St. George's Hall on what is now St. John's gardens. The church cemetery was used as a burial ground for French prisoners of war during the Napoleonic Wars. There is a plaque fixed to the rear wall of St. George's Hall commemorating the French prisoners of war and each year the French ambassador lays a wreath at the foot of the plaque.

The church can be clearly seen behind St. Georges Hall, along with St. Georges place to the left.

The church can be clearly seen behind St. Georges Hall, along with St. Georges place to the left.

The church was demolished in 1898 with St. John's Gardens landscaped soon afterwards.

The Original Liverpool Philharmonic Hall

The old Philharmonic

The old Philharmonic  The new Philharmonic. Original photo by Dave Wood

The new Philharmonic. Original photo by Dave Wood

Built in 1849 on Hope Street to house the Liverpool Philharmonic society to perform concerts to the people, it was destroyed by fire in 1933. By 1939 a new Philharmonic hall was built in an art-deco style, which still exists today.

New Theatre Royal

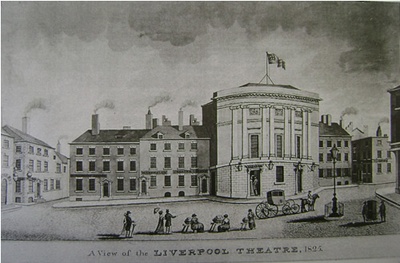

Theatre Royal 1825

Theatre Royal 1825  Theatre Royal Williamson Square 1960's

Theatre Royal Williamson Square 1960's

The original Theatre Royal in Williamson Square was built in 1771. In 1802, the building was demolished and in its place the distinctive curved lined building was erected, the New Theatre Royal.

Actor George Cook made a now famous remark remark in response to being barracked by the audience, "every brick in your dirty town is cemented with a Negro's blood !! ".

Charles Dickens, Irving, Paganini and others appeared at the New Theatre Royal along with a certain local actor Junius Brutus Booth. Junius Brutus's son, John Wilkes Booth, later carried on the family tradition for theatre by assassinating President Lincoln during a performance of Our American Cousins at Ford's Theatre in Washington. In 1896, The New Theatre Royal closed down and the building was converted to a cold storage warehouse. The building was demolished in the early 1970s.

The site is now the home of the official Liverpool Football Club store.

The Shakespeare Theatre

The Hope Street Unitarian Church

Liverpool Sailors home

The origins of the Liverpool Sailors' Home

There were earlier sailors' homes elsewhere. Sailors were thought to be in need of protection from dishonest boarding house keepers eager to take advantage of men who had just been paid. Britain’s first Sailors’ Home was opened in London by the Reverend C.G. Smith in 1835. This was a place where seafarers could live during their time on shore in a port which was not their home port. Efforts to open a similar home in Liverpool soon followed because as the port grew an increasing number of seafarers needed accommodation here.

Establishing a sailors' home at Liverpool The first meeting in support of a Liverpool Sailors’ Home took place on 25 February 1837 and was attended by local shipowners and merchants and other interested people. Nothing came of this meeting because Liverpool’s Council refused to back the plan. However, by 14 April 1841 £1800 (the same as nearly £90,000 in 2001) had been collected in aid of a Sailors’ Home. The plan did not take shape until Liverpool’s Council made land available in May 1844.

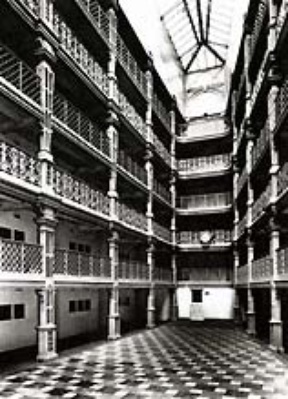

The Sailor's Home in Canning Place, Liverpool was designed by John Cunningham. Influenced by Elizabethan great houses such as Wollaton and Hardwick Hall, the foundation stone of this palatial lodging house for Liverpool seamen was laid by Prince Albert in July 1846 .

The home was a philanthropic venture erected from the subscriptions of shipowners and merchants to provide good, clean and inexpensive accommodation and give sailors a refuge from the grog shops- "drunk for 1d and blind for 2d" - and the attentions of Judies such as Harriet Lane, Jumping Jenny and 'The Battleship'...

In the streets and alleys around the docks there was no shortage of places where 'Seamen's Lodging House' was painted boldly onto a cracked, dirt-specked fanlight and where, at an exhorbitant charge, the sailor would be fed and bedded- after a fashion. Many of these lodging houses were notorious establishments from some of which the shellback would be lucky to escape with his life, let alone his money belt.

If some of the home appeared somewhat like a prison, this was not Cunningham's concept. He modelled the interior upon ship's quarters with cabins ranged around five stories of galleries in the internal rhomboidal court. The columns and balustrades of these galleries were powerfully moulded in cast iron utilising nautical themes such as twisted ropes, dolphins and mermaids. The cast gates were the architect's chef d'oeuvre in iron, a splendid arrangement of maritime buntings, trumpets and ship's wheels, surmounted by the crowned insignia of the legendary Liver Bird - all handled with tremendous virtuosity.

To the great and lasting disgust of many Liverpudlians, this wonderful folly of a building was demolished during the 1970s. Even worse, its site was not even required for new buildings - or even a road scheme.

Chester-based (but Liverpool born and raised) photographer Steve Howe was examining the remaining brickwork in June 2004 when he made a remarkable discovery. Several huge pieces of finely sculpted stonework- including a capstan and the detail of a ship's rigging- remained on the site, largely hidden from casual view by rubbish and vegetation. The discovery was reported to the Merseyside Maritime Museum, which is situated just across the road in the Albert Dock. Nonetheless, these great stones soon afterwards vanished in mysterious circumstances. Information on their present whereabouts would be appreciated!

Steve's Sailors Home page is here: http://www.chesterwalls.info/gallery/sailorshome.html

Some of the remaining stone work. Photograph by Steve Howe.

Some of the remaining stone work. Photograph by Steve Howe.

The site of the Sailors' home is now John Lewis on the Liverpool One area of the city.

A snap of nationalities of the sailors in the home in 1881:

Nova Scotia, Norway, Ireland, United States, Scotland, Swindon (England), Scotland, Newcastle, Cardiff, Bedford (England), Cumberland (England), Denmark, Finland, Chester (England), Malta, France, Orkney, Australia, Scarborough(England), Sweden, Bristol(England), Liverpool(England), West Indies, Isle of Man.

Josephine Butler house

The Original St. John's Market

Wirral

New Brighton Tower

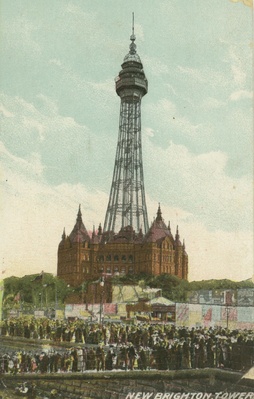

The short lived New Brighton Tower was styled on the world-famous Eiffel Tower in Paris and opened in 1898. The Tower was the highest building in the country at 568 feet and 621 feet above sea level. Four lifts took sightseers to the top of the tower, with views of the Isle of Man, Great Orme's Head, the Lake District and the Welsh Mountains, attracted a half a million people in the year.

During the First World War the public were not allowed to go up the Tower for defence reasons. The steel structure was neglected as there was no income to maintain the tower. Corrosion took hold with the owner unable to afford steel replacement in parts. The tower was demolished from 1919 to 1921. The elegant brick building the tower was built upon, containing the ballroom and theatre remained, later having a cable car onto the building's roof. The ballroom saw acts such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. The Tower building was destroyed by fire in 1969 and demolished after.

Birkenhead Woodside Station

Birkenhead Woodside Station

Birkenhead Woodside Station  Birkenhead Woodside Station

Birkenhead Woodside Station

Birkenhead Woodside railway station was opened in 1878 at the ferry terminal to Liverpool. Trains entered the station via a tunnel from the south. The station was an elegant structure with two semi cylindrical glass roofs covering most the platforms. For such a large structure, the station had only five short and wide platforms, as a roadway ran down the middle of the platforms.

The station building was built the wrong way around. The station was to mesh in with the ferry and tram terminals, however the tram and ferry companies did not build their terminals in the right place. The main booking office ended up being at the back of the station. SAVE Britain's Heritage described the station as "a station of truly baronial proportions and being worthy of any London terminus".

The Beeching plans of the 1960's, called for only Liverpool Lime Street Station to run long distance routes from Merseyside. Liverpool Corporation devised a new metro named Merseyrail metro system which joined all the separate urban railways around Merseyside. [[Merseyrail]] would give access to all of Merseyside from Lime Street station's new underground station. High Level Liverpool Central Station, Liverpool Exchange, Liverpool Riverside and Birkenhead Woodside would be demolished. The station was closed in 1967 and demolished a few years later.

A Fantastic past Liverpool website

A fantastic website here that you MUST visit concerning Liverpool in days gone by. Hundreds of pictures and explanations of where they all are with stories behind them. Click here to visit