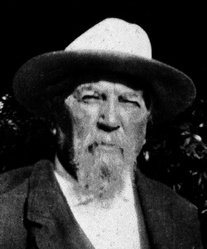

Joshua Chauvet (7/20/1822 - 5/22/1908)

When he first rode into the Valley of the Moon in 1856, Joshua Chauvet took one look at the played out sawmill Vallejo had built some seventeen years before, and immediately recognized the great opportunity he had been searching for.

The enormous forest of redwood and Douglas fir that had once covered the mountainside was gone now, harvested and milled into lumber for building homes. Vallejo had little use for the mill now, and was happy to arrange something of a lease with option to purchase for the young Frenchman and his venerable father, François.

Joshua had arrived in San Francisco some six years before this, with thirteen copper sous in his pocket and dreams of gold on his mind. It had been a difficult sea-voyage of seven months around the Horn from Le Havre, and he was eager to get on to the motherlode to try his hand at mining. A tough childhood had accustomed him to hard work, but that first season was, as it was for most, a miserable disappointment.

The bread Joshua baked for the other miners, on the other hand, proved a far better return for his efforts. His first bakery was in Mokelumne Hill, before he moved on to opening bakeries in Jackson and Sandy Bar.

But flour was quickly increasing in cost to as much as $120 a barrel, while his bread sold for only $1 a pound; so Joshua sent for his father, a millwright and miller still living in France, asking him to bring the necessary equipment, including the two grindstones that stand guard at the entrance to the mill today. The two men wandered around the towns and cities of the region for another year or so, looking for a good place to set up their grist mill; they finally found it at the confluence of Asbury and Sonoma Creeks. It took eighteen months to get fully into operation, but happily their hard work met with eventual success.

Records show that Chauvet fils et père were shrewd businessmen as well as hard workers. As other pioneers arrived to settle the valley they began to function as agents, bankers, and developers, establishing the infrastructure needed by the developing community, including a water system and a brickyard. By 1861 the final purchase of the mill from Vallejo was recorded, including some 500 acres of vineyard, and their place in the valley was firmly established. In 1864 Joshua married Ellen Sullivan, a large and rowdy woman from Ireland who loved her drink. He built a second floor above the mill for his mother-in-law, and with the birth of two sons, Henry and Robert, a multigenerational family began to take shape.

Stage coaches on their way to and from Santa Rosa began stopping at the general store built next to the mill, and the entire valley was quickly settling down to doing a routine business.

While the grist mill continued to operate they also began producing wine and— after a state-of-the-art copper still was brought from France— brandy. But this latter proved to become the downfall of Ellen. Stories of her drinking exploits began to circulate, and Joshua could not leave on business without locking up the winery first.

One time he had no choice but to leave a barrel of brandy outside, so he hoisted it up by ropes into a tree beyond her reach. As soon as he was out of sight, however, Ellen brought out the family rifle and fired a neat shot right through the barrel, catching the stream of brandy in buckets and pitchers and drinking her fill.

Another time, after having had a sufficient amount to drink, she discovered the millrace had sprung a leak. She crawled up to sit in it, thinking her ample body would stop the loss of water; unfortunately, she contracted pneumonia, and soon afterward she died.

A wooden winery was built about that time nearby the mill and store, and while the boys were looked after by a Chinese father and son (each of whom were named Moon) their own father and grandfather tended the various family enterprises until 1881, when François quietly passed away. With his death the grist mill closed down, and Joshua began focusing on the production of wine.

In 1885 a grand three story stone cellar was constructed near the wooden winery. The cellar was considered an architectural marvel of the time, and an indication of what great things could be expected of the young wine industry.

Times were quickly changing; Chauvet shifted from using the primitive waterwheel as a source of energy to the more modern technology of steam power. The railroad replaced the stagecoach line; and when a specially-built railroad spur was constructed across the creek from the cellar, Chauvet's wines became distributed nationwide, gaining recognition and gathering awards.

Henry went away to college to study business, but Robert remained behind to work with his father while becoming captain of the local baseball team. He took after his mother and, sadly, died fairly young of pneumonia— again, apparently from exposure while inebriated, this time in the creek below the mill.

In 1893 Henry married Annie Lounibos, the daughter of a business associate of Joshua’s. The young couple was offered a choice between a trip to Europe and a new home and, perhaps because everybody else still lived in the family compound, they chose to have a great mansion built for them across the new road from the old mill.

While grandchildren began to appear Joshua continued to pursue his several business enterprises aggressively, including a vigorous battle in the courts with his new neighbor upstream, Jack London, over water rights. A new century had begun, with new challenges to be faced as the small settlement became the bustling town of Glen Ellen.

There is a photograph of Joshua in front of the home he had built for Henry, and although he was by now in his 70s he looks fit and self-confident, a man who knows he has earned the respect of the entire region. He died quietly May 22nd, 1908, at the age of 85, and probably very content.