Undated. Courtesy of Mary Hotaling Born: November 7, 1824 in Georgetown, Ohio, a son of John McClellan and Lydia Spencer

Undated. Courtesy of Mary Hotaling Born: November 7, 1824 in Georgetown, Ohio, a son of John McClellan and Lydia Spencer

Died: December 2, 1911 in Northampton, Massachusetts, buried in Cedar Lawn Cemetery, Paterson, New Jersey

Married: Catherine Ann Kinsell (1835 - 1913), November 7, 1858 in Paterson, New Jersey

Children: Daisietta, Katherine Elizabeth, Annie b. January 13, 1871 d. 1871

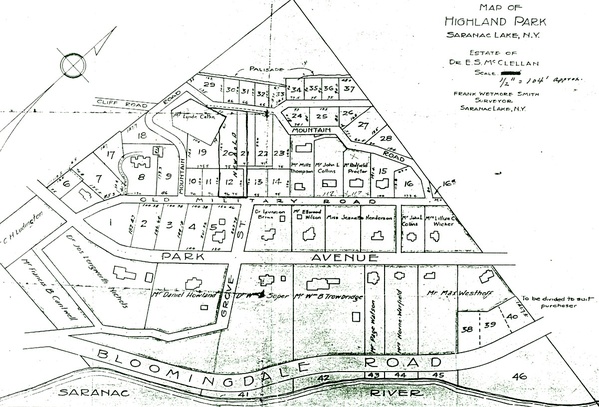

Dr. Ezra S. McClellan moved to Saranac Lake for the health of his daughter, Daisietta. He bought the land upon which Highland Park would be built, adjacent to the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium from Dr. Edward L. Trudeau in 1894. 1 As real estate values were booming, McClellan began to develop the area by 1898, selling parcels with deed restrictions designed to ensure that only expensive residential structures would be built.

After Dr. McClellan's death in 1911, his daughters continued to sell the last few parcels of land within the district through the 1920s.

Source:

Massena Observer, September 8, 1910

PHYSICIAN STRUCK BY TRAIN

Saranac Lake, Sept. 4.—Dr. E. S. McClellan, 80 years of age, president of the board of health for the past twelve years, was struck by a train at the Bloomingdale avenue crossing yesterday, thrown from his carriage and received injuries which may prove fatal. His right arm was broken, his back injured, to what extent physicians have not yet determined, and he was cut and bruised about the body.

Dr. McClellan was accustomed to drive alone, in spite of his advanced years. He is slightly deaf. He was driving north across the tracks and evidently did not see the passenger train approaching from the east. The flagman, who has charge of two crossings about 100 feet apart, shouted to the physician to halt, but the driver did not hear until his horse was on the tracks.

Perceiving his danger Dr. McClellan drew his whip and tried to hurry the animal across the tracks. It was too late, however, and the locomotive struck the rig at the dashboard, throwing Dr. McClellan to one side of the tracks and the horse to the other. The animal was killed.

The aged physician was taken into his home and several surgeons summoned. This morning it was said that the doctor might live.

Dr. McClellan has had a prominent part in the development and growth of Saranac lake. He has been at the head of the Department of Health for more than a decade. He drew most of the health code in force here, and which received the first prize at the International Tuberculosis Congress held at Washington, D. C.

From The World's Work, Volume XXIV, May to October, 1912, A History of our Time, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1912, pp. 584-585. link

Up to 1892, however, nothing really effective was done toward those excellent sanitary measures which were destined to win the medal of a great congress of health experts. Then the man came to the mountain hamlet who was needed to make it what it is — Dr. Ezra S. McClellan of Georgetown, O[hio].

One year after his arrival the first public water supply was turned on. It came from a reservoir on one of the hills, the water being pumped by a turbine direct from the river. Less than twelve months later, a small sewer was laid. This was between 1892 and 1894.

In later years when the rapid growth of the community necessitated re-improvement, and on a larger scale, Dr. McClellan, who in the meantime had become a member of an organized Board of Health, was appointed president of a Board of Sewer and Water Commissioners. It was McClellan's enthusiasm more than anything perhaps — and it shows what one man can do in a community — that led to the installation of Saranac Lake's present excellent water and sewer system. The system itself was planned I believe by Professor Olin H. Landreth of Union College Schenectady.

About this time the supply dam broke and the water supply was badly polluted as a result. Dr. McClellan started legislation to have the dam rebuilt. A measure was introduced at Albany toward this end. On the day before the signing of bills, Dr. McClellan received private information by wire that Governor Black meant to veto the proposition. The valiant doctor jumped on a train and reached Albany and the Governor at the eleventh hour and fifty-ninth second.

"Governor Black," said he, "years ago the state of New York built a dam in the Saranac River six miles above our village. That dam is now dilapidated. The water is frightful. Existing conditions are such that a terrible epidemic of typhoid threatens us. The village of Saranac Lake holds the state of New York responsible!"

It was a terrible responsibility. Governor Black signed the bill and the dam was rebuilt.

Still the Board of Health of Saranac Lake was not satisfied. Again it was Dr. McClellan who questioned the perfectness of the water supply. After lengthy argument the village found itself in a position to advertise its drinking fluid as the real-honey dew — the milk of paradise. The town purchased and deeded to the state an isolated little lake at the base of Mount McKenzie. This natural reservoir, fed by numerous mountain brooks, is surrounded by state forests. Bathing, fishing, even boating are forbidden there. The water is liquid crystal and it is protected by the state for all time.

Incidentally, having now a fine water pressure, another village board organized a fire department and a street cleaning department and bought a sprinkler to lay dust. It is really remarkable what a lot of things can be done with plain water — and soap — and a little ginger!

To go back to the real beginning, it was in July, 1896 that Saranac Lake organized its Board of Health. The best of the town's level heads came together at its meetings. One of the first measures passed was the anti-spitting ordinance. This was in December, 1896. Thus New York City was 1896 City "beaten to it" [...] by several months.

It is characteristic of the admirable solemnity of a country board that this anti-spitting ordinance was not passed for fun, or to satisfy any faction of the ultra fastidious. "Good sanitation as well as good manners required it," said [the residents]. The man of the street and the hotel verandah who punctuates a yarn with deadly expectorate periods, laughed at the ordinance until he found himself haled before a judge. Nowadays an arrest for reckless punctuation is rare in Saranac Lake. To some, the cost appeals strongly: to most, the ordinance is too blessed to be violated.

Next, the Board of Health used diphtheria anti-toxin for the first time in Franklin County, and found it good. Then came compulsory disinfection (by the use of formaldehyde) of all rooms in hotels and boarding houses vacated by persons even suspected of having a communicable disease; and the requirement that hotel and boarding house keepers not only disinfect vacated rooms, but also foot the bill! The Board realized that greater numbers were coming every year to Saranac Lake in search of a cure for tuberculosis and that it would be a terrible burden upon the taxpayers to pay the cost of the fumigations incidental to a transient population of 1,000, more or less, all the time. And so, in most cases, the "extra" creeps into the guest's bills, which is fair enough. In protecting against him, he is being protected against others. This provision of the ordinance probably unique in either codes.

A PRIZE WINNING HEALTH CODE

It was not until 1908 that the which the work which the Saranac Lake Board of had done since its organization in 1896 was published as a completed sanitary code. It was this code which, in the same year, won for the town the silver medal of the Tuberculosis Congress. New York City, I think took, the first prize. This code covers everything imaginable that might touch good health. It even forbids keeping a profane parrot, and abolishing pigs altogether, declares that in Saranac Lake one must not keep chickens. The latter ordinance, to round out perfection with a flaw, is studiously winked at.

In 1908-9 Saranac Lake put the finishing touches to its town by paving the two business thoroughfares and the main residential street, and at the present moment the paving of the whole town is under consideration. Reeking lamps were abolished years ago. All lighting is now by electricity.

Before Dr. McClellan died, he heard men speak of that metamorphosed backwoods hamlet as "the metropolis of the Adirondacks," paved, electric-lighted, modern, yet rurally charming, and with an impregnable sanitary code. He could well say "only seventeen deaths in twelve years from any contagious diseases including typhoid" — and die happy!

Footnotes

1. Lake Placid News, September 3, 1943