There are many ways of telling the story of the city.

Rise and Fall

The story is most often told as a dramatic arc spanning the twentieth century. Because this history is linear and coherent, it is generally represented as the canonical history of the city, and it is often retold by national (and local) media.

The Rise

Campus Martius in the 1890s. Courtesy Virtual Motor City.

Campus Martius in the 1890s. Courtesy Virtual Motor City.

During the first half of the 20th century, Detroit experienced a phenomenal expansion. Between 1900 and 1920, the growth of the auto industry transformed Detroit from a mid-sized manufacturing center to the nation’s fourth largest city featuring a “total industrial landscape.” The growth continued until the 1950s, when the city reached a peak population of 1,849,568 and a peak area of 138.8 square miles of land.

Detroit was considered a model industrial city. Drawn by the promise of high wages and plentiful work, immigrants from the American South and Europe poured into its vast single-family neighborhoods. The union battles of the 1930s made factory work more secure and enabled hundreds of thousands of workers to enjoy a middle class lifestyle. During World War II, more work opportunities opened for women and African Americans, as Detroit's factories switched to wartime production and earned the city the moniker Arsenal of Democracy.

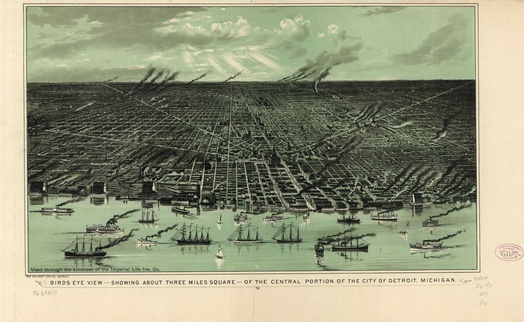

A panorama of Detroit in the late 1890s shows the rapidly expanding city,with factories around the edges, moderate density, and growing bounds.

A panorama of Detroit in the late 1890s shows the rapidly expanding city,with factories around the edges, moderate density, and growing bounds.

During the postwar period, Detroit also became known the world over for its music and culture. Famous acts included blues musician John Lee Hooker, the jazz bands of Black Bottom, and the constellation of artists around Motown Records, including Stevie Wonder, The Temptations, The Four Tops, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Diana Ross & The Supremes, the Jackson 5, Martha and the Vandellas, and Marvin Gaye. The city's rock and roll scene, featuring such artists as the MC5, The Stooges, Bob Seger, Mitch Ryder and The Detroit Wheels, Rare Earth, and Alice Cooper, became nationally famous as well.

The Fall

In the second half of the 20th century, Detroit experienced a decline as precipitous as its initial expansion. Its population fell by more than half, to less than 900,000, and tens of thousands of buildings were abandoned. Detroit became notorious for crime, poverty, and racial stratification.

Many observers have called the 1967 riot/rebellion the decisive turning point in the city's history. That violent civil disturbance claimed the lives of 43 people, destroyed more than 2,000 buildings, and magnified racial tensions between the city's segregated neighborhoods. Historians, however, have shown that the riot was not the cause of Detroit's decline but rather the most visible manifestation of a decline already underway.

The roots of Detroit's decline go deeper, to the social inequalities of the 1940s and 1950s. Although job opportunities widened during the war, African Americans continued to face discrimination in both the job and the housing market. When hired, African Americans were relegated to low paying and often dangerous work. Real estate agents used racial covenants to forbid blacks from purchasing homes in white neighborhoods, and when blacks did purchase homes across the "color line," they faced violence.

These tensions were compounded by the effects of deindustrialization, suburbanization, and urban renewal. In the early 1960s, black neighborhoods, including Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, were demolished to make way for interstate highways and middle class housing developments, destroying long-established communities and creating a critical shortage of housing in the segregated city. At the same time, auto manufacturers, which had begun moving to the edges of the city as early as the 1930s, moved more production outside of the city and began automating factory work, increasing competition for scarce jobs. The construction of highways also enabled white flight to the suburbs, which deprived the city of tax revenue and density.

The flight of jobs, wealth, and residents from the city, combined with the upheaval of existing communities, had a devastating effect on the health of the city and contributed to the crime, poverty, and racial stratification that continue to plague the city today.

Formation and Re-formation of Communities

The narrative of communities in Detroit tells a different social story -- one focusing on the people who made the city rather than its macroeconomic state. It challenges the broad arc of the rise and fall narrative, showing that some communities suffered during Detroit's rise and others thrived during its decline.

Before the auto boom, Detroit's neighborhoods were defined primarily by ethnic origin. Immigrants of varying economic stature but similar origin would live together in ethnic enclaves. The East European Jewish community of the early 1900s was a notable example.

Later, class and race became the salient divisions. The differentiation between white- and blue-collar employment in the auto industry contributed to the further stratification of Detroit, permanently changing social relations. Immigrant neighborhoods came to be defined more by class than ethnicity, as various European descendants shed their ethnic identities and came to identify by economic status and as "white" in opposition to black.

After World War I, when European immigration declined and race divisions hardened, the multi-ethnic neighborhoods of Black Bottom and Paradise Valley became predominately black. They were known as the heart of Detroit's black community until their destruction in the early 1960s by urban renewal. African Americans had few other housing options. Especially during the 1940s and 1950s, the all-white character of other neighborhoods was violently defended.

Today, Southwest Detroit is notable for its growing Hispanic population. The area's growth runs directly counter to the rise and fall narrative, which implies that the city's contraction is universal and inevitable.

Labor

Other communities in Detroit have been focused around wide-reaching issues, like unemployment and labor activism. For example, the union sit-ins of the 1930s brought together workers across the city in mutual-aid groups that mobilized moral and edible support.

Revitalization

Detroit boosters support a new family of narratives about Detroit that emphasize the revitalization or renaissance of specific neighborhoods and communities.

Historical Efforts

Efforts to redevelop Detroit's downtown have been underway for decades. In the 1970s, Mayor Coleman Young spearheaded a series of major development projects with both federal and private sector partners, including the Renaissance Center, Joe Louis Arena, Hart Plaza, the Millender Center, and The People Mover.

Another wave of downtown development began in the late 1990s. Three casinos, first proposed by Mayor Young, received public approval during the administration of Mayor Dennis Archer. Compuware opened its headquarters downtown adjacent to a redeveloped Campus Martius Park, and a collaboration of civic and business interests oversaw the renovation of the Renaissance Center and the riverfront.

Today: Rethinking Urban Identity

More recently, an increase of activity around the arts, culture, and food has raised the image of Detroit. It is unclear whether and how larger-scale economic change in the traditional sense -- an increased tax base -- will follow.

There have also been grassroots efforts to revitalize Detroit's neighborhoods, including the urban gardening movement and the work of community development organizations, neighborhood associations, and block groups to protect and improve the residential areas of the city. Community organizers like Grace Lee Boggs are encouraging Detroiters to build resilient communities, strong local groups that can support themselves to a significant extent.

The Kresge and Skillman foundations have focused on particular areas of the city, concentrating resources in places that would otherwise receive little support from the City, State, and traditional businesses.

These stories are not often told by journalists on the national scale, who instead favor the more entrenched and linear narrative of Detroit's rise and fall.

Sources

There are many excellent books on Detroit history. Other resources used on this page include the Walter Reuther Library at Wayne State University and the photo collections of the Library of Congress.